Of the many hearings that Estes Kefauver held during his two and a half terms in the Senate, the most legislatively fruitful were his hearings into prescription drugs held by the Senate Subcommittee on Anti-Trust and Monopoly, which Kefauver chaired, from December 1959 through September 1960.

The drug industry hearings were part of a series of hearings Kefauver held in the late 1950s and early 1960s on administered prices and the effect of economic concentration on consumers. As biographer Joseph Gorman explained, “Kefauver was concerned about the drug industry for two reasons – first, he was shocked at the tremendous profits drug companies were earning on products for which there was a captive market and among which there was little competition; and second, he was disturbed that drugs were being made available to the public without adequate evidence that they were both safe and effective.”

That first reason linked the drug hearings to the subcommittee’s investigations into the steel industry and the auto industry. In all three cases, the market was dominated by a handful of large firms that unofficially conspired to maintain high prices, putting profits ahead of consumer interests.

It was in that second area – questions about the safety and effectiveness of prescription drugs – where Kefauver ultimately achieved legislative success. However, he tried his best to address both concerns – and his inability to pass legislation keeping drug prices in check continues to haunt us to this day.

Everything Old is New Again

Reading about the drug industry hearings from In a Few Hands is an eerie experience. Some parts are quite dated; for instance, it references drugs like Miltown, which has long been off the market for safety reasons. But Kefauver’s arguments with the executives of the drug companies feel shockingly familiar. Many of the arguments that had during the hearings are the same arguments we’re still having over 60 years later.

Then as now, pharmaceutical companies defended prescription drug prices, saying that the costs were necessary to cover research. The subcommittee, however, showed that drug companies’ revenues were not being plowed into research, but into marketing. For instance, Schering spent 32.5 percent of every dollar earned in sales on marketing and promotions.

In those days, rather than blanketing the airwaves with ads, they flooded doctors’ offices with promotional literature and samples. One physician testified that he received over a pound of ad circulars and samples from drug companies every day; multiplied by the number of doctors in the US, drug companies were shipping over 80 tons of promotional material daily.

Another common thread between Kefauver’s day and ours is that prescription drugs were much less expensive in other countries than in America, even when sold by the same companies. For instance, the subcommittee discovered that US-made drugs sold in France cost 17% of what they did in America.

The hearings also demonstrated the ability of large drug purchasers to obtain lower prices. Today, the debate rages over whether Medicare should be able to negotiate discounts on prescription drugs. In those pre-Medicare days, the bulk purchasers were state and local governments, the Veterans Administration, and the Defense Medical Supply Center. Taking advantage of competitive bidding, those agencies secured prices a fraction of what ordinary American consumers paid. In one case, the military was able to purchase reserpine for 51 cents per thousand tablets, while retail druggists were paying $39.50 for the same quantity.

Then as now, the high price of medications most affected seniors living on a fixed income. At the time, Social Security payments were $60 per month (about $650 in today’s money), and brand-name arthritis pills cost 30 cents each (ten times the cost of the generic version). Within In a Few Hands, Kefauver wrote of the sad reality that still plagues too many seniors today: “[R]egularly toward the end of each month they were faced with the stark alternative of choosing between food and medical treatment. Their budget could not cover both; they could eat and be physically miserable, or they could buy the drug and go hungry.”

Once Kefauver announced his investigation of the pharmaceutical industry, his office was flooded with letters from consumers struggling with the high cost of prescription drugs. Kefauver referenced this in his opening remarks for the hearings. “While this country has the best drugs in the world,” he said, “it would appear from the great number of letters which the subcommittee has received that many of our citizens are experiencing difficulty in being able to purchase them.”

Dirty Deeds (Not) Done Dirt Cheap

The hearings also revealed numerous ethically dubious activities that the pharmaceutical industry committed. Companies that developed new drugs were entitled to a 17-year patent on them, a term the Kefauver already felt was too long. But they had a notorious habit of modifying existing drugs slightly, changing the strength or making other minor adjustments, then releasing the result as a “new” drug with a new 17-year patent period.

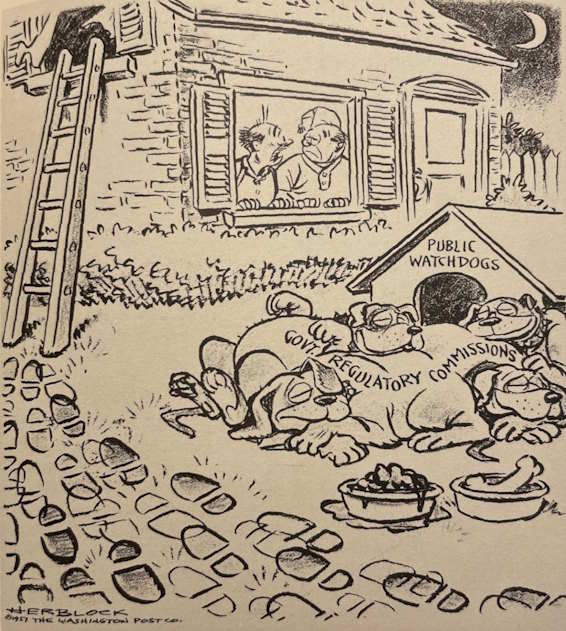

The subcommittee learned of deceptive advertising practices and attempts to hide or downplay harmful side effects. These attempts were combatted ineffectually by the Food and Drug Administration, which the subcommittee found to be woefully underpowered and riddled with conflicts of interest.

For instance, ads for one cortical steroid featured X-rays purporting to show the effects of the drug on a patient with ulcerative colitis. However, not only were the X-rays of different patients, neither one had taken the drug being advertised! In another case, a company that released a new cholesterol drug failed to report to the FDA that animal testing had showed serious side effects. The drug was later pulled off the market after it caused skin rashes and hair loss in patients.

Other revelations from the hearings revolved around the role of the pharma companies’ sales representatives, then known as “detail men.” One example from In a Few Hands involved a drug used to treat rickets and Rocky Mountain spotted fever. The drug was highly effective for its stated use; however, it also caused some of its users to develop aplastic anemia, a disease which killed nearly half of those afflicted.

The FDA allowed the drug to remain on the market, provided that the label and ads contained prominent warnings about the side effects. Worried that doctors would stop prescribing the drug (for good reason), the company instructed its detail men to tell doctors the FDA had given the green light for the drug’s continued use, with no mention of the side effects.

Given the array of troublesome findings that the subcommittee uncovered, Kefauver felt legislation was necessary. The bill that resulted would be Kefauver’s greatest accomplishment… but only after a long and winding path that nearly ended in disaster.

How a Bill (Eventually) Becomes a Law: What They Didn’t Teach You on “Schoolhouse Rock”

In the summer of 1961, Kefauver introduced a bill in the Senate to amend the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. (Representative Emmanuel Celler of New York sponsored the companion bill in the House.) Kefauver’s amendment would shorten the patent on new drugs from 17 years to 3; after the patent period expired, other companies would be able to produce the drug, with a royalty payment to the company that invented it.

Kefauver believed this would significantly reduce drug prices, while still allowing companies to recoup their research and development costs. The amendment also allowed the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare to devise generic names for drugs (previously, this was the sole domain of pharma companies), required companies to list the generic name of drugs in advertising, and significantly expanded the situations in which generics could be prescribed.

In addition, Kefauver’s amendment significantly strengthened the FDA’s power to regulate drugs. It required pharmaceutical companies to show that drugs were both safe and effective before they could be sold. It expanded the FDA’s oversight of drug trials using human subjects and their ability to perform inspections of drug manufacturing plants. The amendment also gave the FDA the right to demand information from drug companies about adverse side effects, rather than forcing them to rely on published journal studies. The amendment also required drug companies to fully disclose side effects and treatment efficacy on drug labels and in ads.

When Kefauver introduced his bill, it was hailed by HEW Secretary Abraham Ribicoff, who said it would “give American men, women and children the same protection we have been giving hogs, sheep, and cattle since 1913” (a reference to the Virus-Serum-Toxin Act).

The bill took the predictable fire from business-friendly Republicans, who considered it excessive interference into the free market. But it also faced attacks from unexpected quarters.

The American Medical Association, for instance, fiercely opposed the proof-of-efficacy provisions in the Kefauver-Harris bill. On the surface, this seemed surprising, but Kefauver explained the source of their antagonism in his book. In the first half of the 20th century, the AMA had taken the lead in certifying drugs as safe and effective. They published an annual volume listing drugs that had received their “Seal of Acceptance,” and only accepted advertising on drugs that had received it. Doctors relied on the AMA as an unbiased source of information about prescription drugs.

In the 1950s, however, the AMA received advice from a consultant that they could make a lot more ad money if they just, you know, quit being so picky. So the AMA dropped its Seal of Acceptance program, stopped publishing its annual volume of useful drugs – and lo and behold, they more than tripled their ad revenue by 1960. Thus, they were no longer interested in investigating the efficacy of new drugs – and they weren’t thrilled about the FDA getting involved, either.

While fending off the AMA’s criticism, Kefauver then faced unexpected intrusion from the White House. Desperate for a domestic-policy win, the Kennedy administration tried to swan in and claim credit for Kefauver’s work. Ignoring the bills that Kefauver and Celler already had on the floor, the administration introduced their own bill through Representative Oren Harris of Arkansas that was considerably weaker, stripping out the price-control provisions from Kefauver’s bill.

Then in early June, James Eastland, chairman of the Judiciary Committee – which had jurisdiction over Kefauver’s bill – arranged a secret meeting with administration officials, drug industry representatives, and Dirksen and Roman Hruska (the two Republicans on the subcommittee). They gutted Kefauver’s bill, making it even weaker than the Harris bill introduced by the administration. Kefauver was not informed of the meeting, and didn’t find out about the rewriting of his bill until Dirksen introduced it before the committee.

Kefauver, ordinarily a very restrained and mild-mannered man, hit the roof. “I’ve never been so disturbed by double dealing in all my life,” he fumed. “I trusted these people. They’ve obviously decided that it would be better to get some kind of bill – the weakest possible – passed now. That way it will be another 25 years before anything more is done.”

Kefauver marched to the Senate floor and gave a speech tearing into Dirksen, Eastland, and the administration for their treachery. “[T[oday a severe blow to the public interest was delivered in the Senate Judiciary Committee… I think the time has come for the spotlight to be turned on so the people of this country can see who is on which side,” he thundered.

Kefauver’s fury temporarily halted the effort to undermine his bill. But what ultimately rescued it was not his anger, but the revelation of a tragedy.

Children of Thalidomide

Thalidomide was developed in the 1950s as a tranquilizer that was prescribed in several European countries to pregnant women to treat morning sickness. Unfortunately, it had not been tested on pregnant women beforehand, and thousands of babies whose mothers used it were born with major birth defects.

News of the thalidomide tragedies erupted in the summer of 1962, while Kefauver’s bill was still in committee, and completely changed the state of play. Overnight, FDA medical officer Dr. Frances Kelsey – who had bent existing regulations to keep thalidomide off the market in the US despite industry pressure – became a national hero. (Kennedy ultimately gave Dr. Kelsey the Distinguished Federal Civilian Service Medal… after Kefauver publicly lobbied him to do so.)

And suddenly, there was a significant public outcry for real drug legislation, and the Judiciary Committee began restoring the safety and efficacy provisions it had stripped from Kefauver’s bill. The bill – now known as the Kefauver-Harris Amendment – passed Congress in August of that year and was signed into law by President Kennedy in October.

Kefauver was present at the bill-signing ceremony – but only because he called the White House to request an invitation. President Kennedy was gracious enough to hand him the first pen used to sign the bill. “Here,” Kennedy said, “you played the most important part, Estes.” A surprised and somewhat bemused Kefauver thanked him.

A Hard-Fought (but Partial) Victory

When the bill finally became law, the New York Times proclaimed Kefauver “the hero of this victory… who doggedly continued to push for this needed legislation despite widespread public apathy, lack of administration interest and bitter opposition from some industry and congressional sources.”

Kefauver’s allies in Congress also hailed his success. Senator Tom Dodd of Connecticut grandly proclaimed: “I have an idea that the Senator from Tennessee will be remembered long after all of us in this chamber at this hour are gone, for many great things he has accomplished [Ed, note: I’m trying, Senator!]… But I think, perhaps, in the long run, a grateful nation will revere his memory most for the passage of this particular piece of legislation.”

As great a victory as the bill was for Kefauver, he lamented the removal of the patent control provisions. “In terms of protection of the public’s pocketbook,” he wrote in In a Few Hands, “this constitutes a serious gap in the law.”

It remains a gap to this day. Kefauver’s prediction that it would be “25 years before anything more is done” turned out to be an understatement. More than 60 years on, we’re still trying to bring down the cost of prescription drugs, and still hearing the same excuses that the pharma execs gave to Kefauver and the subcommittee decades ago.

In this area, as in so many others, we’d have been better off to listen to the man from Tennessee.

Leave a reply to All’s (Not) Fair in Politics and War: Kefauver Proposes a Congressional Code of Conduct – Estes Kefauver for President Cancel reply