I’ve mentioned before how prescient Estes Kefauver could be. Some of the ideas that he promoted are every bit as relevant today as they were then. It was true of his crusade to bring prescription drug prices under control, and equally true of his campaign for electoral college reform.

In 1962, Kefauver wrote an article for the Duke Law School journal Law and Contemporary Problems entitled “Electoral College: Old Reforms Take On a New Look.” At the time, Kefauver was chairman of the Senate subcommittee on Constitutional amendments, and he had recently held hearings into potential reforms of the electoral college system.

The article is over 60 years old, but much of it could have been written last year. Kefauver’s analysis of the problems with our system of picking Presidents remains as insightful now as it was in 1962.

A Landmark Ruling Opens the Door to Reform

Kefauver’s article noted the Supreme Court’s recent decision in Baker v. Carr, which held that federal courts had the right to rule on redistricting cases brought under the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment.

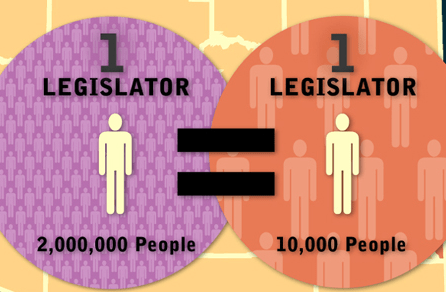

The suit argued that Tennessee’s legislative districts – which hadn’t changed since 1901! – overrepresented rural areas and denied those in urban areas equal representation. After the decision, which Chief Justice Earl Warren called the most important of his time on the Court, 26 states redistricted in the next 2 years.

Kefauver argued that the Baker decision paved the way for a serious look at electoral college reform, because it meant that urban residents and groups –historically underrepresented in the US House and state legislatures – might be more open to the discussion.

At the time, the consensus was that the electoral college – especially the “unit rule” giving all of a state’s electoral votes to the candidate who got the most votes in that state – was biased toward large states and cities. “As urban interests gain their proportionate voice in state legislatures,” Kefauver reasoned, “they should be more willing to give up their favored position in presidential elections.”

Kefauver Says No to the Status Quo

From the outset, Kefauver acknowledged the difficulty of his task. “Past efforts at electoral college reform have produced little more than sympathetic amusement among hard-nosed realists of politics and government,” he wrote.

He also acknowledged that reform advocates had hurt their own cause by failing to agree on an alternative. “The existing system was imperfect to enough people but for too many different reasons,” Kefauver lamented.

Kefauver laid out the shortcomings of the present system, using the 1960 election as a vivid example. “As the electoral college lumbered like an oxcart through the selection of America’s President for the space age,” he wrote, “its machinations sounded several alarms.”

The alarms may be eerily familiar to modern audiences:

- In Illinois, where cries of election fraud were rampant, the GOP-controlled Election Board threatened not to certify Kennedy’s win in the state.

- In Hawaii, dueling slates of Democratic and Republican electors were both certified.

- Alabama Democrats fielded a slate of 6 unpledged electors and 5 Democratic electors; voters who wanted all the state’s electoral votes to go to John F. Kennedy – or for all to be uncommitted – had no way to choose that outcome.

- Those uncommitted electors – as well as other unpledged electors from Mississippi and a faithless Republican elector in Oklahoma – voted for Senator Harry Byrd of Virginia, who was not a candidate.

- After Election Day, the Louisiana legislature tried to suspend their election laws so they could appoint a slate of unpledged electors too.

“The only conclusion which can be drawn,” Kefauver noted, “is that there is a great gulf between our presidential election system as it is popularly viewed and as it actually exists.” He pointed out that many features that we typically associate with Presidential elections aren’t actually in the Constitution.

For instance, nowhere does the Constitution require that states award their electoral votes to the candidate who wins the majority of the state’s votes. “For the past eighty-five years, each state has appointed its electors by popular vote,” Kefauver wrote, “but this continues only at the sufferance of state legislatures and not as a matter of right.”

He also pointed out that the Constitution has no mechanism for preventing or disciplining faithless electors. “Extra-constitutional devices such as pledges, statutory instructions, and the short ballot [listing the names of the Presidential candidates instead of the electors] have largely guaranteed elector fidelity,” he wrote, “but there is little doubt that each elector is still constitutionally free to vote for whomever he chooses in December, regardless of the manner in which he was ‘appointed’ in November.”

Kefauver noted the most common criticism of the existing system is that the candidate who gets the most votes in a state gets all of its electoral votes, whether he wins the state by one vote or one million. Kefauver observed that the unit rule is also not in the Constitution; it’s just a convention that states choose to observe.

Not only that, there was nothing to stop states from changing how they appointed electors from election to election for partisan gain. (In 1892, Democrats in the Michigan legislature switched to awarding their electoral votes by district in a blatant attempt to help Grover Cleveland win back the White House. Those following recent events in Nebraska may feel a sense of déjà vu.)

Weighing the Options

Kefauver named two types of objections to the status quo: practical (those “concerned with the mechanics of the system’s operation”) and philosophical (concerns that the popular-vote winner might lose the election, or about the balance of power between states or rural and urban areas). The alternatives that he considered focused on those philosophical objections.

Option #1: National Popular Vote

The first alternative he considered is the one favored by many electoral college reformers today: scrapping the college altogether and electing the President by nationwide popular vote. “The chief advantage of this proposal is obvious;” Kefauver said, “it would completely eliminate the possibility of a so-called ‘minority President,’ which cannot honestly be claimed for any other proposal.”

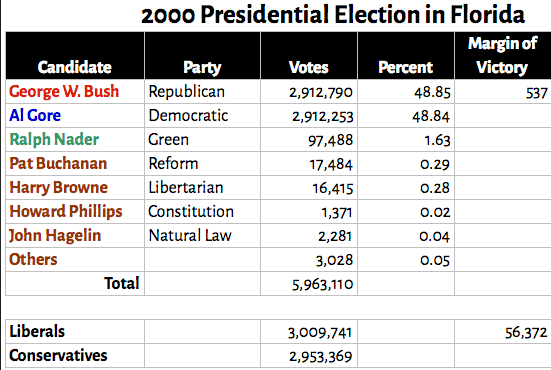

At the time of Kefauver’s essay, the popular-vote winner had lost the election three times: in 1824, 1876, and 1888. Since then, it famously happened in 2000 and 2016. (Kefauver noted that there were several “near misses” in 1844, 1884, 1916, and 1948, where a few thousand votes the other way in one or two key states would have produced a minority President.)

Nonetheless, this approach had been rejected repeatedly by Congress and was also not the preferred option in a poll Kefauver conducted of university political science departments.

Why? Once key concern was that it would diminish the role of states and of groups who might be able to swing a particular state, but not a nationwide election. “State and regional interests are still sufficiently important that sheer numbers of votes on a national level should not determine the Presidency,” Kefauver argued. He also pointed out that a nationwide popular vote would likely require national election laws and federal administration of elections, which would give some people heartburn.

The biggest problem, in Kefauver’s eyes: it would never pass. States advantaged by the existing electoral college system would never vote for an amendment to abolish it.

“If hope is ever abandoned for other reforms and we are faced with a choice between direct national election and the present system, this proposal might take on a different light,” Kefauver concluded. For the time being, he felt that the idea “conflict[ed] too greatly with our federal principles and some deep-seated facts of political life.”

Option #2: The District System

The second alternative Kefauver explored was awarding electoral votes by district. The proposal under consideration at the time would have awarded two electoral votes in each state to the winner of the statewide vote, and its remaining electoral votes to the winner of each district. (The original proposal allotted votes by Congressional district; a revised version created separate Presidential elector districts.)

One issue, Kefauver noted, was that many states were so dominated by one party that allotting votes by district wouldn’t change the distribution of electoral votes that much. The primary effect would be to split the electoral votes of “populous states with distinctive rural and urban areas,” thus diluting the power of large states in the electoral college.

The bigger issue is one familiar to modern audiences: gerrymandering. This proposal would only increase the incentive for state legislatures to twist Congressional district lines to benefit their party. (We think of techniques like “packing and cracking” as a modern invention, but Kefauver showed otherwise, dubbing the practice “divide and conquer partitioning.”)

The revised proposal aimed to fix this by creating “Presidential elector districts” that were designed to be compact, contiguous, and as equal in population as possible (features distinctly not common to Congressional districts in those days). But to Kefauver, this created as many problems as it solved. Having Presidential elector districts that didn’t overlap with Congressional districts would likely confuse voters. Who would draw these districts? The same state legislatures that loved gerrymandering Congressional districts? Congress? The courts?

Also, how would the “compact, contiguous, and equal” provisions be enforced? As we’ve seen many times, court challenges on redistricting issues can take years to resolve. And the 2000 election demonstrated the outrage that ensues when the outcome of a Presidential election is decided in court.

If you left it to Congress to reject certification of electoral votes from states with improperly drawn districts… at best, Congress would likely decline to press the issue (since they’d never declined to seat members or punished states for voting rights violations in the past). At worst… well, you get January 6, 2021. (Kefauver pointed out that this could get even uglier if you left it up to Congress to redraw districts in states that didn’t comply with the rules.)

Option #3: The Proportional System

Finally, Kefauver described his preferred solution, the “proportional system.” In this system, individual electors would be removed from the equation. Instead, each state’s electoral votes would be awarded proportionately based on the percentage of votes each candidate received in the state. No districts, no gerrymandering. (If you’re wondering how this differs from a direct popular-vote system, it would preserve the existing distribution of electoral votes, which gives more weight to smaller states.)

Kefauver declared it “the reform which best meets the principal evils of the present system while introducing a minimum of new complications or inequities.” (The political scientists he polled agreed; 46.9% favored the proportional system.)

According to Kefauver, the primary concern with this plan is that it would encourage “splinter parties.” To counter this objection, the proposal would require the winning candidate to get at least 40% of the electoral votes. If this didn’t happen, the election would be decided by Congress – but unlike the current system where the House decides the Presidency with one vote per state delegation , the vote would include both the Senate and the House, and each member getting a vote. In this event, the choice would be limited to the top two vote-getters, essentially eliminating the chance for a “splinter party” victory.’

In fact, by eliminating the winner-take-all apportionment of state electoral votes, Kefauver noted that this system would reduce the ability of third parties, especially those with particular strength in a state or region, to play spoiler. (Those who remember Ralph Nader’s role in the 2000 election will understand the issue here.)

Another criticism of the proportional system – one popular with Republicans of the era – is that it would be biased toward Democrats because of the “Solid South.” The handful of electoral votes that Democrats would lose in Southern states, they argued, would be far outweighed by the larger proportion they’d gain in more competitive states.

Kefauver pointed out that the South wasn’t nearly as solid as it used to be. “Having seen Tennessee go Republican in 1952, 1956, and 1960,” he wrote, “I am painfully aware that in presidential elections the two-party system seems to have arrived in the South.” Besides that, “an argument based upon shifting patterns of sectional party strength should not control in evaluating the soundness of a constitutional system to be used over a long period.” (Indeed, a few decades later, it would be Republicans benefiting from the “Solid South.”)

Another critique is one commonly lobbed at nationwide popular-vote proposals today: It would lead to more disputed election counts. Instead of disputes and recounts being limited to a handful of swing states during a close election, partisans would be looking everywhere for disputed votes that might change the outcome.

Kefauver conceded this point, but argued that “[t]he temptation to cry or commit fraud and to challenge election results will be much less when the shift of a handful of votes in a state can no longer tip inordinately great blocks of electoral votes from one column to another.” He acknowledged that close elections would still be disputed, but “[a]s 1960 demonstrated, such an election will always bring uncertainty in determining the final results.”

In short, Kefauver felt that the proportional system would address the shortcomings of the status quo while ensuring that states still mattered. “Real damage to our federal principles could result if parties and candidates become unconcerned with state interests,” he warned.

Two “Quick Fixes”: Eliminate Electors and Fix Contingent Elections

Regardless of which reform was chosen, Kefauver believed one change was mandatory: the electors had to go. In Alexander Hamilton’s original conception of the system, electors were men of reason who used their independent judgment to select the best candidate. In practice, however, electors were tasked with voting for the candidate who won their state’s popular vote.

Noting that the number of faithless electors had increased in recent election cycles, Kefauver wrote, “why should any risk be taken that a few individuals could some day miscarry an election when they have long since ceased to serve their intended purpose and are at best an imperfect conduit?”

Kefauver’s solution: a simple amendment “which provides that the state’s electoral vote will be automatically awarded to the winner of its popular vote as has been the virtually uniform practice for 135 years.” Besides eliminating the faithless-elector problem, this would also prevent states from submitting slates of unpledged electors, with “their potential for manipulation and balance-of-power bargaining in a close election.”

(Kefauver had a very good reason to worry about these things, as there had been a very real and concerted attempt to steal the 1960 Presidential election using these tools. We have somehow memory-holed this entire incident, but it’s worth remembering! I’ll share that story in the next installment of this series.)

Along with scrapping electors, Kefauver proposed changing how we decide contingent elections where no candidate wins an electoral college majority. As described in the section above, such elections would be decided jointly by the House and Senate with one vote per member.

As amendment that got rid of electors and changed the system for deciding contingent elections, Kefauver wrote, “would at least perfect the present system as it is generally expected to function. It would provide a certain and uniform system which could not be manipulated from state to state or from election to election.”

To those who worried that passing that amendment would kill momentum for bigger reforms, Kefauver said not to worry. He felt that the amendment “is sufficiently worthwhile of itself to justify the slight risk of hampering further reform… [It] would at least put our present electoral house in order while we continue the debate of whether to rebuild its basic structure.”

Epilogue: A Moment Missed

Kefauver understood the long odds of any sort of electoral reform occurring. “It has been 158 years since the constitutional method of electing the President was touched in any respect,” he wrote, “and it would be most presumptuous to make specific claims for the future.”

Sadly, his words of caution proved justified. Kefauver’s subcommittee advanced two reform proposals: one based on the district system, and another with Kefauver’s preferred proportional system. As the Senator foresaw, the pro-reform side’s inability to coalesce around a single solution wound up dooming them both. (Kefauver’s death in 1963 also deprived the cause of a powerful advocate.) His proposed amendment to eliminate electors and change the way contingent elections were decided also went nowhere.

After another chaotic Presidential election in 1968, Congress nearly mustered up the will to act. The Celler-Bayh Amendment would have abolished the electoral college and gone to a nationwide popular vote, with 40% required for election. (If nobody reached 40%, the top two candidates would advance to a runoff.) The House passed the proposal by an overwhelming margin. President Nixon endorsed it. The Senate Judiciary Committee voted in favor of it. It looked like enough state legislatures would be willing to ratify it.

Everything was going great, until a coalition of Southerners and small-state conservatives filibustered the proposal in the Senate. Two attempts to break the filibuster failed, and the Senate tabled the proposal, never to pick it up again.

Today, we still have the same system for picking Presidents as we did in 1962. All the problems and dangers that Kefauver warned us about are still there. And we’re no closer to solving those issues now than we were in his day.

2 responses to “Electoral College Dropout: Kefauver and Election Reform”

[…] Electoral College Dropout: Kefauver and Election Reform […]

LikeLike

[…] reading Estes Kefauver’s article on electoral college reform (which I covered in detail last week), I shook my head that, 60 years later, we still haven’t fixed the myriad problems with our […]

LikeLike