If there was any single issue that was central to Estes Kefauver’s political career, it was antitrust and corporate monopoly. Throughout his time in the House and Senate, Kefauver was deeply concerned that concentration of economic power in large companies would allow those companies to exploit consumers, workers, and citizens. He waged a decades-long fight to rein in the power of corporations.

Given that the mid-20th century was a time of massive corporate conglomerates, Kefauver’s fight was often a lonely one; he often received little support – if not outright opposition – from the leaders of both parties. But it was in this area that Kefauver had his greatest legislative achievements.

Standing Up for Small Business

Kefauver’s first important work on this issue began when he became chair of the House Small Business Subcommittee. In the fall of 1946, he announced the launch of hearings to see what could be done “to reverse the trend toward economic concentration.” In his announcement, he stated that the “trend toward concentration of production and distribution of goods into the hands of fewer and larger companies constitutes one of the gravest issues of our times.” He said that his investigation was “vital to all groups – business, labor, agriculture and consumers – who have a stake in the maintenance of a competitive enterprise economy.”

Kefauver’s hearings turned up startling statistics about the growing rate of economic concentration. They found that over 1,800 companies had been purchased or swallowed by merger since 1940; the country’s 18 largest corporations alone had gobbled up almost 250 smaller companies. The subcommittee also found that the government had worsened the problem during and after the war through its contract with the largest defense companies. The final report of the subcommittee, entitled “United States Versus Economic Concentration and Power,” was so thorough and impressive that it was still considered definitive 15 years later.

Based on the findings of his investigation, Kefauver turned his attention to potential solutions. He proposed a bill to strengthen the Clayton Antitrust Act, eliminating a loophole in the act that allowed companies to reduce competition by buying up the assets of their competitors.

Introduced in 1947, the bill was promptly ignored by his Congressional colleagues, who were focused on trying to pass the anti-union Taft-Hartley Act. In response, Kefauver took to the House floor to ask, “[I]s this Congress going to make itself ridiculous in the eyes of history by passing a stringent bill against the problem of monopoly in labor, while at the same time ignoring the much greater problem of monopoly in industry?” (His bill finally passed as the Cellar-Kefauver Act in 1950.)

In December of ‘47, Kefauver spoke out against a bill permitting “voluntary price agreements” among sellers, supposedly intended to stabilize commodity prices. In Kefauver’s eyes, the bill was an invitation for corporations to conspire against consumers. “Monopoly interests and their Republican spokesmen in Congress,” Kefauver charged, “have now seen fit to strip from the consumer the last shreds of protection which he possesses against the rapacity and greed of monopoly business.”

He went on, “I defy any member of this House to cite a single illustration of a conspiracy by big business which resulted in lower prices for the consumer… Monopolies always conspire to raise prices, and never to reduce them, except for the deliberate purpose of eliminating smaller competitors, after which prices are raised to new heights.” He was ultimately successful in scuttling the bill.

The following year, Kefauver published a paper in the American Economic Review stressing the importance of greater antitrust action. He stated his belief that communities with a great number of independently-owned businesses had higher “standards of human welfare” than those dominated by “a few large plants owned by distant and outside interest.” He also wondered whether “a great concentration of industry would inevitably lead to [a] collectivistic state in which our democratic liberties and political rights would cease to exist?” The link between economic freedom and political freedom was a theme that Kefauver would emphasize throughout his career.

In his paper, he proposed several recommendations to strengthen antitrust enforcement, including greater appropriations for enforcement, a crackdown on corporate mergers, and even the breakup of existing companies that controlled too large a percentage of an industry.

Exposing Corporate Conspiracies in the Senate

Kefauver’s focus on issues of monopoly and economic concentration continued unabated after his election to the Senate. While defending the Celler-Kefauver Act in 1950, he asked his colleagues: “Shall we permit the economy of the country to gravitate into the hands of a few corporations?” He would devote some of his finest years in the Senate to examining that question.

In 1953, the Senate Judiciary Committee established a Subcommittee on Monopoly and Anti-Trust; Kefauver was one of its founding members. In 1957, after the completion of his Vice-Presidential campaign, Kefauver became the Subcommittee’s chairman. He would focus on the subcommittee’s work for the remaining years of his life.

That January, Kefauver announced that the subcommittee would hold hearings “industry by industry” to examine “the effect [of economic concentration] on free enterprise and especially small business.” The hearings began that summer; by the time they were done, they would fill 26 volumes and over 18,000 pages with their findings.

Throughout the subcommittee’s years of detailed and grueling work on these issues, Kefauver was guided by a set of questions that he asked his staff whenever they questioned whether all the effort was worth it. “Is it right? Is it in the public interest? Does it need to be done?” Kefauver would ask. When the staffers answered each question in the affirmative, the Senator replied, “Well, then, we had better go ahead.”

At the outset of the hearings, Kefauver explained that that the subcommittee was “trying to come to grips with… the Nation’s current No. 1 domestic economic problem – the problem of inflation.” In his view, one of the primary drivers of inflation was the phenomenon of “administered prices.”

The theory of administered prices, originally developed by economist Gardiner Means, held that in industries that were dominated by a handful of large corporations, prices tended not to be dictated by supply and demand, but rather by the whim of the dominant firms, seeking to maximize profits. Or as Kefauver summarized it in his book on the hearings, In a Few Hands, “An increasing number of important industries in our economy have acquired – and continue to acquire – a built-in immunity to the forces of the market.”

The subcommittee’s hearings demonstrated just how pervasive that immunity to market forces could be, and exposed the fun-house logic that the executives used to defend their anti-competitive practices.

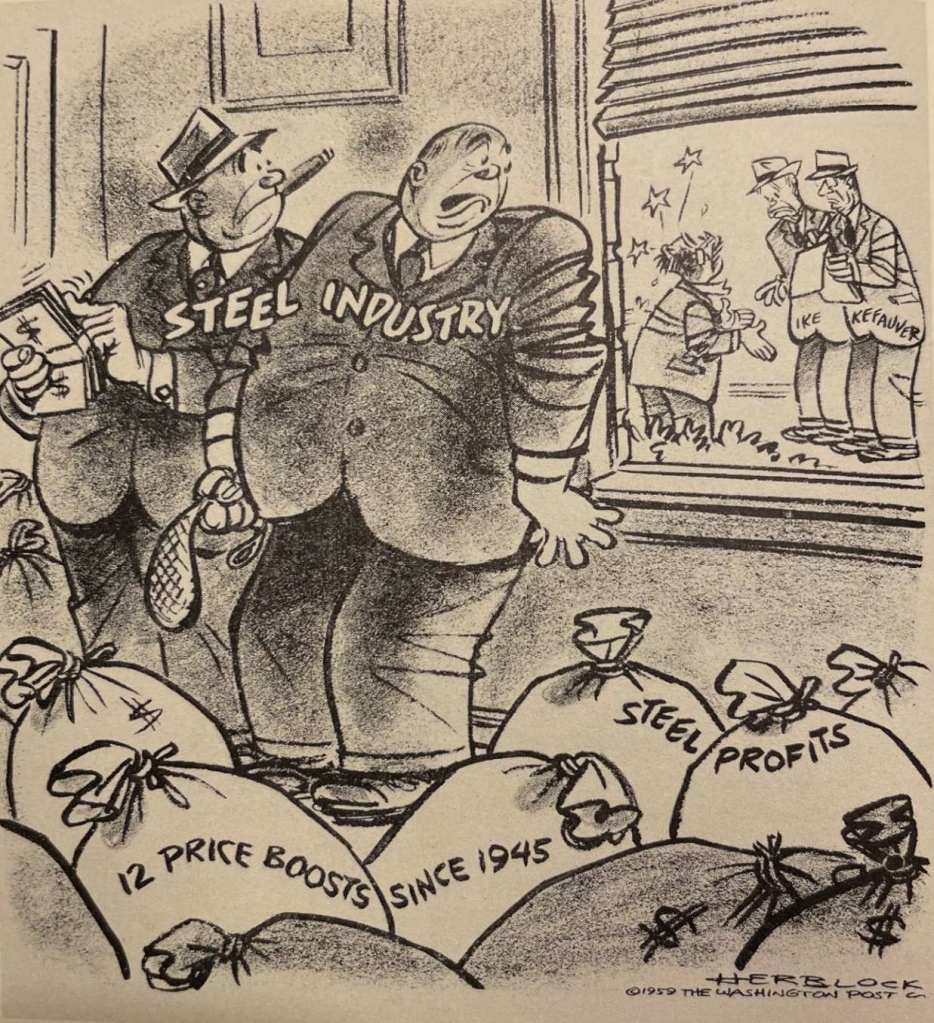

In the steel industry, for instance, the subcommittee found that the American firms charged identical prices to the leading firm, U.S. Steel, even though several competing firms had lower production costs and were operating well below capacity. Roger Blough, chairman of U.S. Steel, defended the industry’s anti-competitive behavior with this logic-mangling statement: “My concept is that a price that matches another price is a competitive price… I would say that the buyer has more choice when the other fellow’s price matches out price.” (Kefauver sardonically replied: “That’s a new definition of competition that I have never heard.”)

Other steel firms employed the same warped logic as Blough. George Humphrey, chair of National Steel and former Treasury Secretary under Eisenhower, testified before the subcommittee. Kefauver pointed out that National’s production costs were lower than U.S. Steel, but that they were running at only 80% of capacity. Why not lower their prices and increase market share? “[I]f we made a lower price everybody would meet it,” Humphrey replied, then took the argument to the point of absurdity: “It is not going to help this country or anyone else if we go down to a point where this industry does not make any money, and it will hurt the Government very seriously if that should occur.”

The president of Bethlehem Steel made the same ridiculous slippery-slope argument, claiming “you can carry it on to the point where you would not be making any money… you will end up that the last one in the business will be the most efficient one, and the rest of them will be out, and you will have a monopoly with one company supplying our country with whatever steel they can supply them, and it will not be enough[.]”

In the drug industry hearings, Schering president Francis Brown was even more blunt in defending his company’s high prices, saying, “Schering cannot expand its markets by lowering prices… After all, we cannot put… two people in every hospital bed when only one is sick.”

The hearings also exposed corporate behavior that seemed straight out of Kefauver’s organized crime hearings a decade earlier, in which dominant corporations acted like the Mafia trying to muscle smaller competitors out of business.

In the bread industry, for instance, corporate bakeries tried to buy up their independent competitors at under-market prices. When the smaller bakeries refused, the corporations sold loaves under cost in the home markets of the smaller competitors, paid supermarkets for favorable placement, overcrowded store shelves with their products to squeeze out the smaller bakers, and even persuaded the Teamsters and baker’s union locals to demand wage hikes from independent bakers.

The hearings into the auto industry didn’t reveal mob-like competitive tactics; instead, they revealed a never-ending game of follow-the-leader. The leader was General Motors, which made over half of all new cars sold in America at the time. The subcommittee found that GM had an annual target profit rate of 15-20%, and it hit that target every year except during the Great Depression. In the decade after World War II, they averaged a 25% annual profit.

Their competitors, meanwhile, followed GM’s lead on prices. In 1957, Ford initially announced it would raise its prices an average of 3% over the year before; a week later, when GM announced a 6% increase for ’57, Ford promptly raised its prices to match (and Chrysler followed suit). Rather than attempting to compete on price, the Big Three attempted to win customers with annual styling changes and ever-larger cars with more powerful engines.

The subcommittee wound up concluding that GM held too large a share of the market, and recommended that the Justice Department take action to break up GM (and possibly Ford and Chrysler as well). This recommendation was ignored, but Kefauver presciently forecasted in the pages of In a Few Hands that foreign competitors would respond to consumer demand for smaller, more efficient, and better built cars if the Big Three continued to ignore it; Japanese and European automakers wound up doing precisely that about a decade later.

The subcommittee survived several attempts by Republicans to undermine its work. In 1958, Senate Minority Leader William Knowland of California led an effort to slash the subcommittee’s budget. His efforts were met with fervent pushback; even fellow Republican Everett Dirksen of Illinois, an unabashed supporter of big business who served on the subcommittee and frequently disagreed with its conclusions, defended its important work and the performance of his “able and affable friend from Tennessee.” Knowland’s motion was voted down by a 61-28 margin.

In 1961, conservative critics attacked the subcommittee again, this time accusing it of going beyond its scope and generating plenty of headlines but little actual legislation. Kefauver stoutly defended his subcommittee’s work on the Senate floor, calling its work part of what Woodrow Wilson called the “informing function” of Congress, and pointed out that “no meaningful bill can even be drafted until the facts of the matter are known and understood.”

And by the time of Kefauver’s death in August 1963, the Subcommittee on Anti-Trust and Monopoly had achieved quite a bit more than headlines.

A Proud Legacy… and an Example for Today

In the fall of 1958, the Tennessee Valley Authority sought bids for a new generator at one of its power plants. Although it was a sealed bid process, General Electric and Westinghouse submitted almost identical bids – less than $70,000 apart on a $17.5 million bid – while a British firm submitted a bid that was almost $5 million lower. Upon further investigation, the TVA found a pattern of identical sealed bids from multiple companies for electrical components.

Kefauver’s subcommittee launched hearings into the matter, which attracted the attention of the Justice Department. Their investigation ultimately led to GE and 28 other companies receiving over $2 million in fines and seven executives being sent to prison, with 23 others received suspended sentences.

But the landmark accomplishment of the subcommittee under Kefauver came as a result of its hearings into the drug industry in 1959 and 1960. The story of those hearings deserves to be told in full, and I’ll cover it in a separate post. They resulted in what was arguably Kefauver’s landmark accomplishment as a Senator, the Kefauver-Harris Drug Act of 1962. Among other things, the Act required pharmaceutical manufacturers to prove that their products were both safe and effective in order to sell them.

With less fanfare, Kefauver shepherded another antitrust bill through Congress that year. Called the Antitrust Civil Process Act, the law empowered the Attorney General to demand corporate records as part of a civil antitrust investigation without having to convene a grand jury first.

This law stemmed from the subcommittee’s own bitter experience. In 1962, at the urging of the Kennedy administration, the subcommittee subpoenaed the 12 largest steel companies for price data in order to determine whether their planned price hikes that year were justified. Several companies defied the subpoena, and when the subcommittee voted to hold the companies and their officers in contempt of Congress, the full Judiciary Committee voted to override them.

(The subcommittee got no help from the White House, who had made the request in the first place. Once President Kennedy was able to convince the steel companies to cancel the planned price hikes, the administration lost interest in the data. This wound up costing them the following year, when the steel firms hiked their prices over administration objections. That cost data the subcommittee wanted probably would have helped!)

Beyond their legislative impact, the subcommittee hearings also opened the public’s eyes to the many ways in which corporations took advantage of consumers. “It is astonishing what a variety of rapscallions this one investigator has exposed,” the New Republic wrote of Kefauver. “…[I]t is not without cause that the felonious element in American business hates the man. And the force of their hatred has lifted him out of the ruck of anonymities whose period in Washington has benefited none but themselves and has put the Tennessean in the relatively short list of those whose membership in Congress has profited the country as a whole.”

Ironically, Kefauver’s death in 1963 came at a time when big business was at a high tide of power and influence. As a result, even many of Kefauver’s admirers felt that his anti-monopoly efforts were a quixotic crusade against an inevitable future. The New Republic wrote in their eulogy of Kefauver, “He was a legacy from the past – from the muckrakers and the progressives – when it was still fashionable to believe that the people were the ultimate repository of wisdom and virtue. His faith is today largely discredited, But the new age which is dawning has yet to discover a new faith to replace it.”

As it turned out, the “new age” that they mentioned would demonstrate that Kefauver’s faith was far from discredited.

One of Kefauver’s last major efforts in the Senate was an attempt to establish a federal Office of Consumers. He envisioned the office as “a daily burr in the hides of Government officialdom to get important consumer issues raised, and to aid in their settlement in such a fashion that consumer interest will be heard and taken account of.” He raised this bill in three successive Congresses, 1963 being the last.

Although Kefauver’s federal Office of Consumers wasn’t established, in the decade-plus after his death, a major grassroots consumer movement emerged in America, led by activists like Ralph Nader. Though Nader and his compatriots weren’t elected officials, they were heirs to the Kefauver tradition. So is Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren, who has made a career out of exposing the ways the banking and finance industries take advantage of the average American.

Nader and Warren, carrying on Kefauver’s fight.

The issues of monopoly and the power of big business are arguably even more vital today than they were in Kefauver’s era. His concern about economic concentration threatening the people’s political power echoes through our ongoing debates over the power of social media to influence our elections and political debates. Kefauver would no doubt be as concerned about the power and influence of Amazon, Google, and Facebook today as he was about General Motors and General Electric in his time.

“Just as there is no end to the task for making our social institutions responsive to the needs of the people,” Kefauver wrote in In a Few Hands, “so it is with the equally arduous job of maintaining a competitive economy.” Those words are as true today as when he wrote them 60 years ago. Kefauver was a tireless fighter for the people in that never-ending struggle. We should strive to follow his example.

Leave a reply to Kefauver on Cars, Part 2: Let’s Get Small – Estes Kefauver for President Cancel reply