It might seem logical that Estes Kefauver’s interest in reforming the Electoral College began after he ran for President in 1952 and 1956. In truth, however, he had long understood the shortcomings of our system for electing President, and had started calling for the abolition of the Electoral College even before he arrived in the Senate.

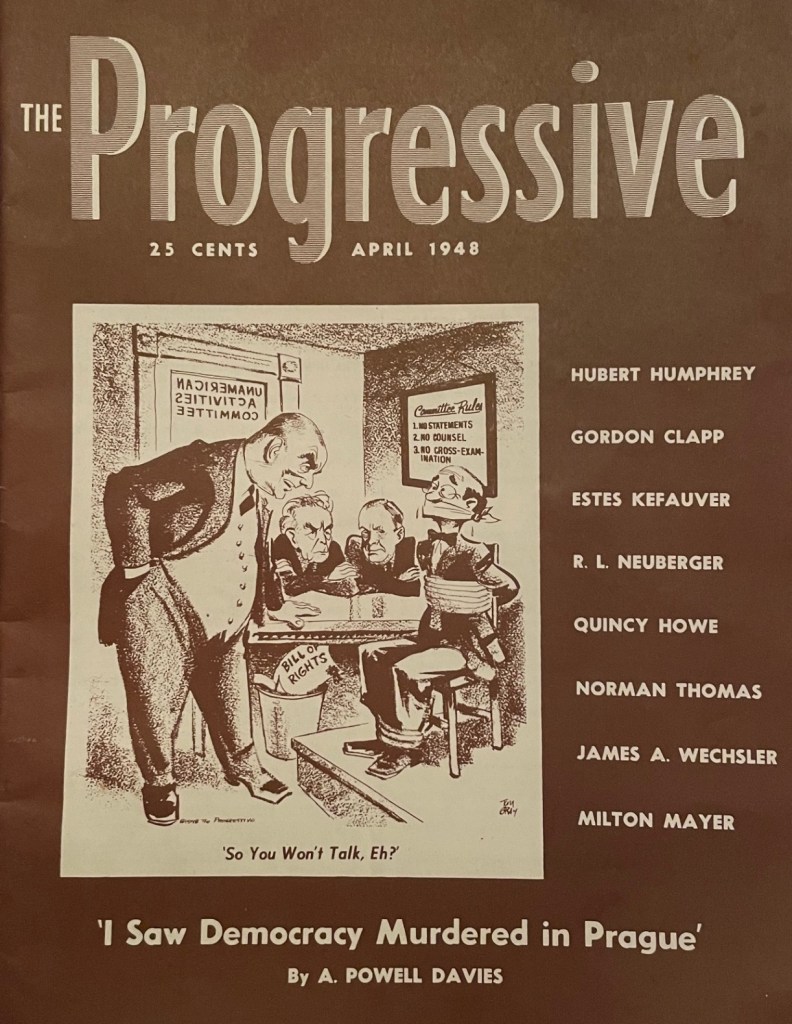

Need proof? Let’s talk a look at an article he wrote in The Progressive magazine in April 1948, entitled “A College for the Ashcan.”

(As an aside, that particular issue of The Progressive had a real All-Star list of contributors. In addition to Kefauver, the issue included contributions from future Oregon Senator Dick Neuberger, six-time Socialist Presidential candidate Norman Thomas, TVA director Gordon Clapp, and newsman Quincy Howe, who would moderate the Kefauver-Stevenson primary debate in 1956. The headliner was future Senator and Vice President Hubert Humphrey, writing on the seemingly evergreen topic of “What’s Wrong with the Democrats?” (I may have to cover that piece in a future post.)

The article demonstrates that Kefauver perceived and articulated the weaknesses of the Electoral College system from early in his political career. Comparing this article to the one he wrote on the same subject in 1962, there are a lot of similarities.

In both articles, he expressed deep concern about faithless electors casting ballots for the wrong candidates, the winner-take-all electoral vote system that focuses campaigns on a handful of swing states, and the possibility of third-party candidates playing spoiler in close elections.

One key difference in the 1948 Progressive article, however, is that Kefauver was writing much more from his perspective as a Southerner.

A good deal of the article revolved around the potential threat of revolt by Southern electors refusing to support the Democratic nominee in the Electoral College. Given the article’s timing, this might make Kefauver seem clairvoyant, since the 1948 convention – and the accompanying Dixiecrat walkout – hadn’t happened yet.

But Southerners had tried a similar stunt four years earlier, and they were already making noises about doing so again in response to President Truman’s special message to Congress that February calling for a package of civil rights legislation.

What’s interesting is that while Kefauver condemned the Southerners’ attempts to hijack the Electoral College, and called for changing the system to prevent it, he seemed at least somewhat sympathetic to what they were trying to accomplish.

Pointedly declining to weigh in on the merits of Truman’s proposed civil rights legislation, Kefauver instead focused on the idea that the South’s interests were frequently ignored in national politics. “[I]t is clear that the national leaders of the Democratic Party regard the South as ‘safe,’” Kefauver wrote. “Since it is confidently expected that the South will vote Democratic no matter what policies are followed by the Democratic Party, the national leaders of the party are under little compunction to give adequate consideration to the special problems of the South.”

Not only did the South’s issues get snubbed, Kefauver argued, so did their candidates for higher office. “Since both national parties are mainly concerned with winning the electoral votes of the doubtful states and since the South is hardly ever doubtful,” he wrote, “a system has developed of political discrimination against Southerners in the selection of Presidential candidates.” (Although he had not yet run for President at this point, you get the idea that he was thinking about it.)

But if Kefauver agreed with the rebels that the “South is pitifully neglected” by the national parties, he staunchly opposed their method of fighting back. He denounced the idea that “a revolt in the Electoral College provides an instrument for the political liberation of the South,” calling such a strategy “short-sighted and self-defeating.”

So what did Kefauver think would help the South’s plight? Genuine two-party competition. If the Democrats couldn’t take the South’s electoral votes for granted, they’d be forced to take the region’s interests more seriously. Similarly, if the Republicans had a chance to win votes there, they’d be incentivized to appeal to Southerners, rather than just writing the region off entirely.

Kefauver’s solution for this: allocate electoral votes proportional to each party’s vote in a given state or district. Under the winner-take-all system, it didn’t matter if the losing party got 49% of the vote or 4%; either way, they received no electoral votes.

In order to deal with the third-party-spoiler problem, he proposed abolishing the requirement that the winning candidate receive a majority of electoral votes; instead, whichever candidates had the most electoral votes would be declared the winner. This would also dramatically reduce the chances of elections being thrown into the House, which Kefauver considered terribly anti-democratic.

He noted that this was actually closer to the spirit of the original Electoral College system. Initially, electors were chosen in most states on a district-by-district basis. (The Federalists abolished this system in their states in 1800 in hopes of propping up John Adams’ failing re-election bid; the Democratic-Republicans quickly followed suit.)

This approach provides a window into Kefauver’s thinking about politics. He was a deep believer in America’s democratic system and the idea that the will of the people should prevail. However, he did not believe that the Constitution was a magical, flawless document.

When circumstances changed over time or the actual practice of politics revealed flaws in the system as designed by the Founders, Kefauver believed in making amendments to fix it. He most definitely did not believe in exploiting flaws in the system for the benefit of a particular party or faction.

“The answer to the problem,” he wrote, “is not to misuse an already defective process but rather to iron defects out of the system.”

Kefauver acknowledged that the Founders had conceived the Electoral College as a group of independent actors. “It was intended to avoid, on the one hand, the popular tumult and passion that a direct election by the people might involve,” he wrote, “and on the other hand, it was intended to avoid legislative domination of the executive by the Congress.”

In practice, however, the system never functioned as the Founders envisioned, due to the formation of political parties. “The electors… became only robots or puppets,” he wrote, “selected under a moral restraint to vote for a particular person in a particular party.”

But those “moral restraints” were not accompanied by any legal restraints on the electors’ behavior. At the time of Kefauver’s article, only two states (California and Oregon) had legislation requiring electors to vote for the ticket that won the state’s popular vote.

Given that, he concluded that “the only clear-cut way to remove the threat of a revolt among the electors is to abolish the electors themselves as entities differing in any way from the voters to cast their ballots at the polls.”

Sadly, the Electoral College reforms Kefauver sought were not adopted in 1948, or afterward. As it turned out, the South never staged a successful Electoral College revolt, instead – as Kefauver recommended – becoming open to voting Republican.

Unfortunately, after being competitive for a generation or two, the South eventually became a one-party region again, this time solidly Republican instead of solidly Democratic. Whether the region will ever really get the hang of two-party competition remains to be seen.

If we would make the Electoral College reforms that Kefauver advocated, I think it would help. If the Democrats wanted to show a real commitment to competing everywhere, they’d do well to dust off Kefauver’s old playbook.

Leave a comment