If you’re reading this site, odds are you’re a fan of American political history. Since that’s the case, you probably know that the first televised presidential debates occurred in 1960 between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon. Famously, Nixon’s haggard and sweaty appearance on camera caused JFK to be considered the winner of the debates, even though those who listened to the debates on radio felt that Nixon had won.

If you are familiar with this bit of political history, congratulations! Just one problem: it’s wrong.

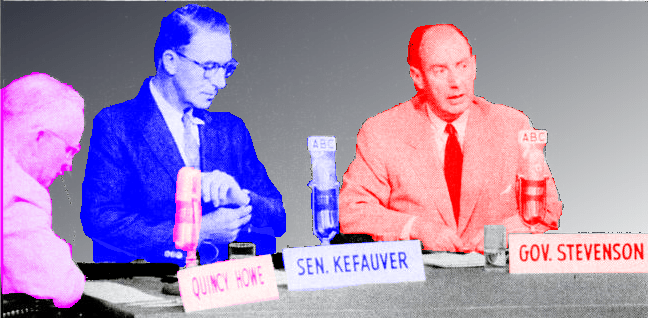

Sure, Kennedy and Nixon held the first televised general-election presidential debates. But for the first presidential debates of any kind to appear on the tube, you need to go back four years earlier, when Estes Kefauver and Adlai Stevenson faced off in the midst of the hotly contested 1956 Democratic primary.

This debate occurred on May 21, 1956 in the studio of station WTVJ in Miami, but was broadcast nationwide. The debate came at a pivotal time in the campaign. The Florida primary occurred one week after the debate, with the California primary coming a week later. With Kefauver having scored an upset win in Minnesota and Stevenson having taken Oregon, the Florida and California primaries were considered must-wins for both candidates. (As it turns out, Stevenson won both, all but ending Kefauver’s chances for the nomination.)

The debate lasted about an hour, with the candidates discussing a wide variety of issues including atomic bomb tests, America’s diplomatic posture toward the Soviet Union, military spending, civil rights, the plight of small farmers, and more.

Unlike modern debates, the hallmark of this one was how frequently the candidates took virtually identical positions on issues. As the New York Times wrote in their recap of the debate, “Senator Estes Kefauver and Adlai E. Stevenson canvassed their political differences for an hour on television tonight and found very little to disagree about.”

Nor did the candidates result to personal insults to paper over their policy agreements; the tone of the debate was quite civil, with only the mildest of jabs here and there. For those accustomed to the insult-comic style of modern politics, the amiable tone of these proceedings is downright refreshing.

And thanks to the magic of YouTube (and the grace of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum), you can see it for yourself here:

For those who don’t have an hour to spare, or who would like some context on the highlights of the proceedings, my thoughts are below:

- Our moderator is Quincy Howe, a longtime newspaper, radio, and TV commentator. Breaking things down for viewers who are unfamiliar with the debate format, Howe describes his role as “kind of a traffic cop,” who will move the candidates along if they spend too much time on a subject or slow them down if they speed through a question too quickly.

- Kefauver begins his opening remarks with a reference to the hydrogen bomb test that America had conducted the day before the debate, the first in a series of tests known as Operation Redwing. The US dropped an H-bomb from a B-52 over Bikini Atoll at a height of 50,000 feet; the bomb detonated at 15,000 feet, thus proving that it could be used as an airborne weapon. “There can be no mistake that we are now face-to-face with a double-edged possibility of total destruction and the possession of total destructive power,” Kefauver notes somberly. He calls for bilateral discussion with the Soviets about a mutual halt to nuclear arms testing, a “crash program” to produce more scientists, and greater focus on peaceful uses of atomic energy. He also says that “[w]e must turn [the H-bomb’s] very terror into the last best argument for world peace. We cannot continue on a path past hope and fear.”

- Stevenson focuses his remarks on the importance of the idea of America. He quotes President Sukarno of Indonesia, who wanted to visit America because it is “the center of an idea.” To Stevenson, the central question of the campaign is, “What is America about, what does it mean, in this midpoint of the 20th century?” He vows to restore American strength and leadership, and describes the ongoing battle between America and its allies and the Communist bloc for the allegiance of “the great uncommitted peoples of the earth.” This is a theme he will return to repeatedly during the debate.

- Given the news about the H-bomb tests, it’s no surprise that the first half of the debate focuses on foreign policy. At the outset, Kefauver tries to establish a difference between the candidates by dinging Stevenson’s call for a unilateral halt to nuclear testing. Kefauver argues that we should wait for a good-faith agreement from the Soviets before halting tests. Stevenson defends his position by noting that it’s impossible to test an H-bomb in secret, so we’ll be able to tell if the Russians are violating the agreement. Kefauver replies that Khrushchev had recently announced his intention to continue missile testing, saying that this indicates bad faith. Stevenson says that he never proposed stopping development of missiles, and the candidates skirmish briefly over whether it’s possible to test missiles separately from warheads before letting the matter drop.

- Both Stevenson and Kefauver knock the Eisenhower administration for allowing the US to fall behind other countries on the development of atomic energy for peaceful use. Kefauver calls out the administration for leaving the development of nuclear plants to private industry, while Stevenson stresses the importance of providing nuclear energy to those “uncommitted” developing countries.

- Those of you who read this site regularly will understand why Kefauver was so pleased with himself when he worked a Dixon-Yates reference into his answer on atomic energy. For those unfamiliar, you can read the story here.

- Howe asks the candidates to comment on the “new Soviet look,” referring to Khrushchev’s policy of de-Stalinization and his recent decision to cut back on the size of their ground troops. After initially ignoring the question both times Howe asks, the candidates agree that it’s more of a propaganda move – and a recognition that the possibility of nuclear reduces the need for a large standing army – than anything. Kefauver holds out the possibility that this could be a good-faith opening, provided that the Soviets are willing to allow free and fair elections in Poland and the Baltic states. Stevenson again returns to those uncommitted countries, saying that the US will need “some ingenious ideas if we’re going to compete for their allegiance, especially in the direction of peace.”

- The first domestic issue that Howe brings up is segregation, specifically school segregation in the wake of the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education. This isn’t a comfortable issue for either candidate, as they need to avoid saying anything too pro-integration (to avoid losing votes in Florida) or too pro-Southern (to avoid losing votes in California). They both wind up with essentially the same answer: the Supreme Court’s ruling must be obeyed and desegregation is the right thing, but that it will need to be done carefully to avoid a major backlash, and that prominent leaders of both races will need to work together to smooth the transition. Kefauver points out that Southern anti-black prejudice is not the only problematic form of discrimination in the country, citing prejudice against Hispanics and Asian-Americans.

- Kefauver’s answer on civil rights name-checks Florida Governor LeRoy Collins, one of several times when he references Florida-based issues and politicians throughout the debate. He seems much more inclined than Stevenson to tailor his answers for the audience in Miami, while Stevenson seems more aware that the debate is being broadcast nationally.

- Kefauver ties the struggle for civil rights in America to the struggle against colonialism and oppression around the world. He tries to quote a line he had used the month before about the winds of freedom blowing around the world, but he can’t remember it, so he winds up on “The winds of freedom and the demand to be equal and have rights are all around the world today,” which is barely even a coherent sentence.

- Howe’s question about Texas and LBJ is fairly opaque to a modern audience, so a bit of context: Governor Allan Shivers led a faction of conservative Texas Democrats known as “Shivercrats.” In 1952, Shivers endorsed Eisenhower over Stevenson for President (and would do so again in ’56), helping facilitate the General’s win in the state. The Shivercrats fought for control of the Texas Democratic Party with a more liberal faction led by Lyndon Johnson and Sam Rayburn. The incident that Howe mentioned was a debate over which faction would represent Texas at the Democratic convention, a debate won by the Rayburn/LBJ faction. Stevenson and Kefauver, unsurprisingly, were both happy about this outcome. (The Shivercrats eventually wound up in the Republican Party along with most other Southern conservatives.)

- Howe invites the candidates to ask a question of each other, leading to Kefauver’s biggest mistake in the debate. He takes issue with Stevenson citing his not-infrequent absences from Senate votes, noting that there was a reason for his absences in each case (in 1948, he wasn’t yet in the Senate; in 1950 and 1951, he was traveling the country for the organized crime hearings; in 1954, he was in a tough re-election race). This complaint is a hanging curveball for Stevenson, who says that he was merely responding to a question from reporters about why Kefauver’s Presidential bid had so little support from his Congressional colleagues, and speculating that his frequent absences might be the reason. Kefauver tries to save face by pointing out that Stevenson was surely absent from the governor’s chair frequently during his Presidential run in 1952, but Stevenson retorts that the legislature wasn’t in session them. The whole exchange is a self-inflicted disaster for Kefauver, who would have been better off not asking anything.

- Howe asks Kefauver what issues he’s hearing about from voters on the campaign trail. He mentions the plight of small farmers, who are facing falling prices and rising expenses. He recommends price and income supports for family farms as a solution. Stevenson agrees that the plight of small farmers is an important issue, noting that the farmers’ struggles also hurt the small businesses in farm towns as well as agricultural equipment manufacturers.

- Stevenson’s mention of small businesses gets Kefauver off and running on his favorite topic, namely the danger that “we will have more and more of this country in the hands of fewer and fewer people.” He proposes revision of antitrust laws to lengthen the notification period on proposed mergers, favorable tax treatment of small business, and greater federal support for small business (along the lines of what the then-new Small Business Administration will later do). Stevenson agrees that small businesses need help, but (as usual for him) seems more interested in the philosophical implications of the “problem of bigness.”

- In his final question, Howe asks the candidates to evaluate the effectiveness of different methods for reaching the public. Both agree that TV is very effective for reaching many people at once, but that it’s expensive (Kefauver in particular notes that his cash-strapped campaign can’t afford much TV time). Kefauver stands up for the importance of shaking hands and meeting people in person, poking fun at Stevenson for his having recently shaken hands with a mannequin in a department store. (Stevenson’s somewhat bizarre response: “I found her very tempting.”)

- For the closing statements, Howe asks each man to address the issue of “why I am a candidate.” I found these statements the most illuminating part of the whole debate. Even though Kefauver and Stevenson’s issue positions were quite similar, you could learn a lot about the differences between them by listening to the closing statements. (They begin at the 48:06 mark of the video.) Stevenson begins by saying that no one should run for President “to serve a personal ambition or just because you want the job,” a blatant jab at Kefauver. In his mind, the right reason to run for President is because you have deep convictions about your party’s principles and the issues facing the world. He talks about the important issues facing the country and the world such as war and peace, resource conservation and development, the Bill of Rights, and the need to show a sympathetic understanding of the problems facing underdeveloped nations in order to beat back the challenge of the Soviets. To Stevenson, the Presidency – and the Cold War – is all about philosophies and ideas. It’s a political science professor’s view of the Presidency. Kefauver, meanwhile, lists off all the things he’d like to accomplish as President, the policies he’d like to enact and the constituencies that would benefit from his help. His is a much more pragmatic take on the Presidency than Stevenson’s; if you want to get things done, you have to come up with specific policies and work to make them happen. Kefauver is not indifferent to big ideas – indeed, he has a deep reverence for the American founding principles of democracy, self-government, and human freedom – but he understands that great ideas and intentions are meaningless unless you do the work and round up the votes to turn them into reality. Kefauver quotes Sir Thomas More, who wrote, “The things, Good Lord, that I pray for, give me Thy grace to labor for,” and says that he would like to labor for the issues he mentions and to lead the American people in getting them. It’s why, as much as I admired Stevenson and his intellect, I believe Kefauver would have been a more effective President: because he wanted to be a doer-in-chief, not just a thinker-in-chief.

I don’t know if the debate wound up changing many minds in the primary. But it set the stage for decades of televised debates to come, as the primary political battleground shifted from smoke-filled back rooms to voters’ living rooms.

One response to “Lights, Camera, Action!”

[…] someone’s legacy can look when you look at it through different lenses. When I watched the Kefauver-Stevenson debate from 1956, Kefauver came off as the practical, hard-nosed realist in comparison to Stevenson’s ivory-tower […]

LikeLike