We Americans frequently debate about our political system. We debate how representative our representative democracy really is. We debate whether it’s really a democracy or a republic. We debate whether our elected officials care what the voters want, or if they’re just doing the bidding of their biggest donors. We debate whether to raise or lower the voting age, whether to abolish the Electoral College, whether to expand the House, and even whether to get rid of the Senate.

One thing we rarely debate is the responsibility of the people in our political system. Any American citizen over 18 who hasn’t been convicted of a felony (depending on the state) is legally permitted to vote. But how much of a responsibility do citizens have to inform themselves before voting? And is voting enough, or are citizens also responsible for holding politicians accountable after they’re elected? If so, how do they do that?

As I said, we don’t discuss these questions much nowadays. But Estes Kefauver cared a great deal about them. To him, active citizens were the key to making America work.

In the spring of 1951, fresh off his tenure as chair of the Senate subcommittee on organized crime, Kefauver gave a speech about what he believed Americans needed to do to continue the fight against crime. The speech laid out his vision of the role that both public officials like himself and citizens played, not just on organized crime, but in the American system of government.

The Perilous Problem of Public Apathy

Kefauver’s speech was part of the Sixth National Conference on Citizenship. The conference, jointly sponsored by the National Education Association and the Justice Department, was a forum for leaders in a variety of fields to discuss the meaning of citizenship in America. (The organization still exists today, and still holds annual conferences; their 2025 conference takes place this week.)

The theme of the 1951 conference was “Freedom in One World: Today and Tomorrow.” With America now the world’s most powerful nation, what was American citizens’ role in promoting freedom and democracy both at home and around the world?

Organized crime was only tangentially related to the conference’s theme. I suspect the organizers wanted to leverage Kefauver’s newfound fame to drum up interest in the conference. But the Senator managed to make the topic relevant, by focusing on the problem of public apathy and the damage it does to communities.

Kefauver framed his argument by quoting his future Presidential rival, Adlai Stevenson, on the major causes that allowed crime to flourish. Stevenson cited the usual suspects: corruption, bribery, underpaid and understaffed police forces and prosecutor’s officers.

The last factor Stevenson mentioned, though, was public indifference, adding “that you could put out all of the [other causes] and just leave [apathy] and you would have the entire and complete picture.”

Kefauver agreed with Stevenson’s view. While he acknowledged the need for changes in federal and state laws, he argued that they would be meaningless without “an aroused public opinion, interest by the citizens at the local level.” Replying to those who looked to the federal government to combat organized crime, “I say conditions will be just as good as the people back home want them to be.”

What was Kefauver’s evidence of public apathy? Disinterest in voting, for one. “It is only through the exercise of our right of the ballot… that we have any way of managing our government,” he said.

He noted that voter turnout in the 1948 election was barely above 50%, and that turnout in off-year and local elections was even lower. Those weak numbers, Kefauver argued, made it easier for criminals to get a foothold in local government.

“You can be quite certain,” he said, “that the criminal and the racketeer who is looking for protection… gets his people out and he uses his influence and his money to see that candidate are elected who are going to be kind to him.”

He noted that when his subcommittee went into “wide open” cities where illegal activity was broadly tolerated, “The public officials felt they owed their election to the money and the influence of the racketeers, that they had to have it, and that they couldn’t be reelected if they went against their wishes.”

The real blame, Kefauver believed, belonged not to the craven or corrupt officials but to the citizens who couldn’t be bothered to vote them out. “You hear a great many people, preachers, educators, say, ‘What are you going to do about it?’ Asked if they vote, ‘Oh, well, we didn’t pay much attention to that.’”

But citizens’ responsibility didn’t end with voting, Kefauver argued. “[T]oo many Americans, if they do vote, forget about the public official,” he said. “They do not advise him constructively.”

He argued that citizen advice should not just involve criticism, but also praise for a job well done. “When officials stand up for the good of the masses… there is no encouragement frequently from the good citizens,” he said. “Public officials not only need to be able to rely upon you [to vote]; they need to be backed up by you after they have been elected.”

Kefauver’s news wasn’t all bad. He noted with approval the formation of local crime committees, estimating that 35 to 40 had been stood up in the wake of the subcommittee hearings. “Not only are they going to keep the spotlight of public attention upon officials to see that they enforce the law,” he said, “but they are… going to back up honest officials, and in that way we are going to going to have good government.”

Strong Communities Deter Tomorrow’s Criminals

Kefauver said that engaged citizens were critical not just to combatting crime, but to avoid creating a new generation of criminals. Based on the testimony from the crime hearings, Kefauver believed that the existing crime bosses were beyond saving. But he held out hope that the younger generation might not follow the same path.

The subcommittee asked the criminals who testified, “What started you into a life of crime?” They had many reasons, but there was a common theme. “Many of them said, ‘It just didn’t seem like anybody cared what happened to me,’” Kefauver explained. “There was no association, no group, no good citizen who took an interest in the child, and he went on his way and made a bad start.”

Like Hillary Clinton a half-century later, Kefauver believed it took a village to raise a child. Presaging his future juvenile delinquency hearings, he argued that communities had a responsibility to provide children with the material and emotional support that would allow them to thrive.

“if you go to a city where there are good schools and churches and recreational facilities, interest in children, and people making a fair living and no slum areas, you are not going to find very much crime,” he said. “If you go to a city where kids are playing in the mud puddles and living in slum conditions, the schools are down and the churches are not taking very much interest, then you have a hotbed of criminal activity.”

(If this formulation seems a tad naïve, you’re not wrong. But 75 years later, we’re still struggling to answer the same questions.)

This speech illuminated Kefauver’s approach to government. Throughout his career, critics frequently complained that his public hearings succeeded in attracting attention, but failed to solve the problems that he spotlighted. But he never expected the hearings to solve the problems on their own, certainly not in the case of a complex problem like organized crime.

As Kefauver saw it, his hearings were meant to shine a spotlight on a problem and stir up public attention. After that, however, it was up to the citizens to take the baton, either by lobbying their elected officials to pass necessary legislation or by getting active in their communities.

Are We Up to the Challenge?

Did Kefauver expect too much from the people in terms of active citizenship? Some of the other conference speakers thought so.

Kefauver’s speech was followed by a panel of radio and newspaper reporters who discussed the issues he raised. They agreed that public apathy was a genuine problem. However, they also offered some perspective.

Agnes Meyer, who reported on social issues for the Washington Post, said that in her travels around the country, “I found that our society has been so shattered by two world wars and a depression that people are isolated. They feel isolated… They are isolated in our big urban cities, and as a result they think that the individual no longer counts and that personal efforts such as voting are futile.”

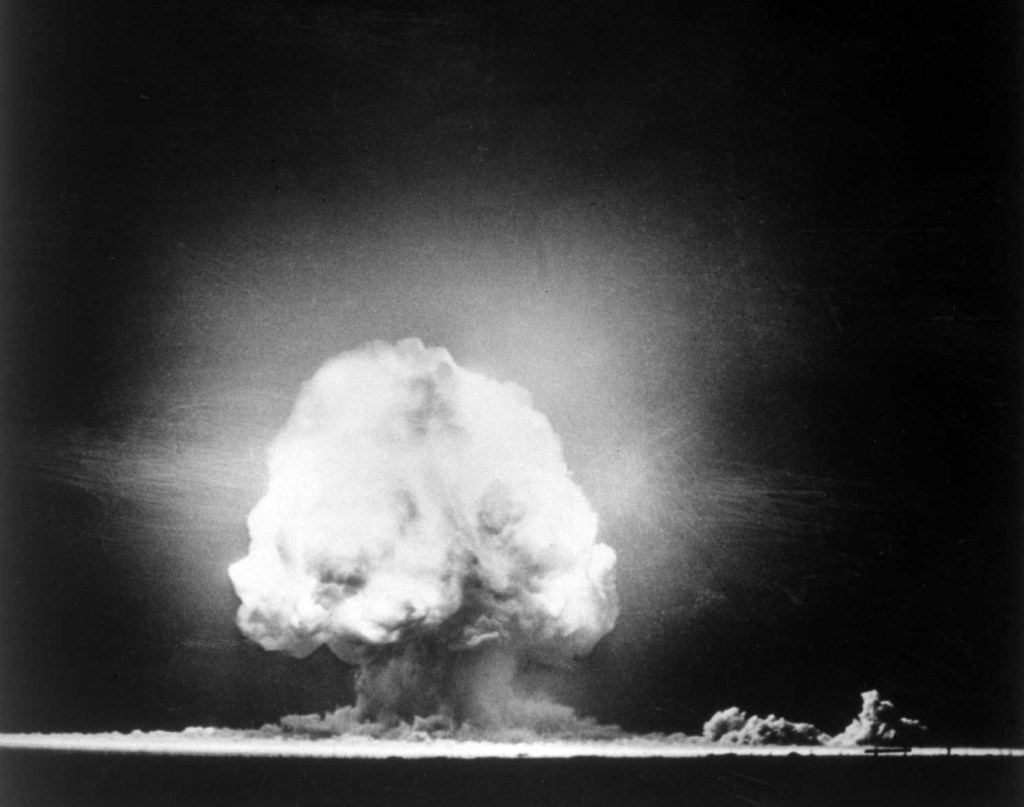

Ruth Montgomery of the New York Daily News agreed that the Kefauver Committee hearings “should terrorize us into doing something,” but noted that Americans were being told to be alarmed about everything from the atomic bomb and civil defense to the Korean War to juvenile delinquency. “I think Stalin eventually will lick us just by ulcers if we aren’t careful,” she quipped.

Meyer and Montgomery both had valid points, ones that have only become more salient in the decades since. Many people today feel more disconnected from their neighbors and communities than ever; we look back at the Fifties as a golden age of community in comparison. And in our modern social-media age, there’s no shortage of issues that people demand that we be outraged and/or terrified about on a daily basis. How’s that working out?

Still, I think Kefauver was also right. We don’t talk nearly enough about the responsibilities of citizenship. And if it’s true (as his critics believed) that Kefauver was too idealistic about our political system and our citizens, I’d rather be too optimistic about my fellow Americans than to give up hope.

Our country is full of cynics who complain about corrupt and out-of-touch politicians, who proclaim our system of government broken beyond repair, who argue that the only solution is to burn it all down or blow it all up.

To those people, I say: What are you going to do about it? Firing off angry posts on social media doesn’t count.

Vote, write or call your representatives, volunteer for candidates and causes you believe in. Run for office if you’re so inclined.

As Kefauver said, conditions will be just as good as the people want them to be. Want a better, cleaner country? Grab a mop and get involved.

Leave a reply to A Unified Theory of Kefauver – Estes Kefauver for President Cancel reply