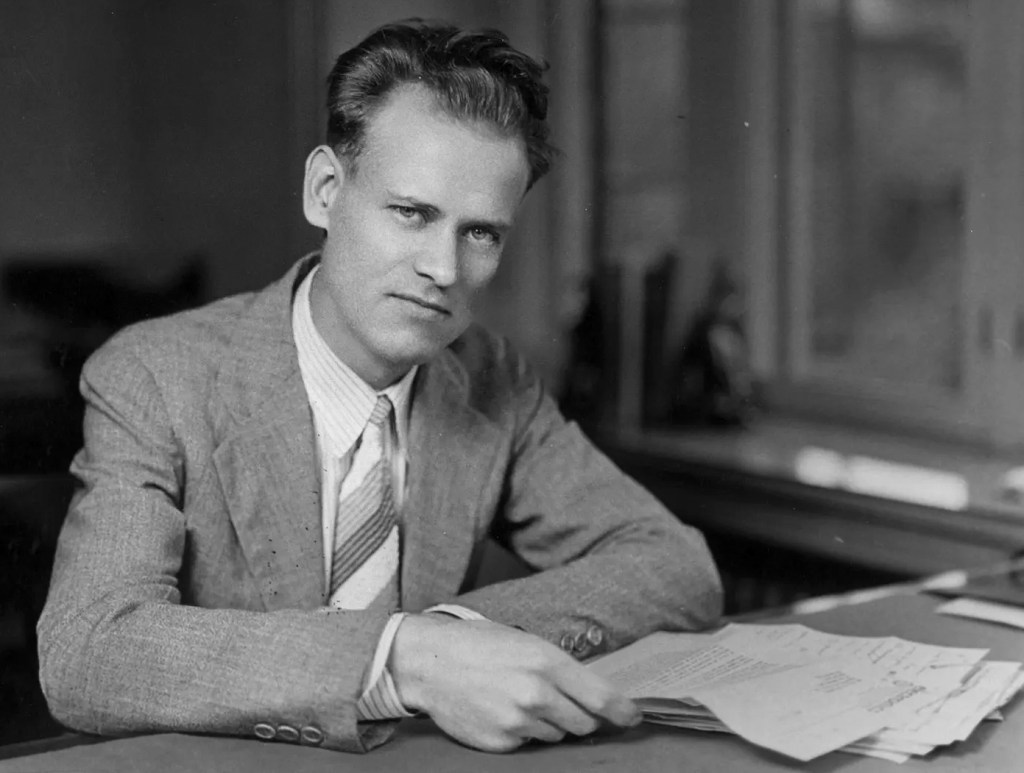

Have you ever heard of Philo Farnsworth?

Odds are that you haven’t. Farnsworth was a Utah-born inventor who developed electronic television, which had a revolutionary impact on our society and culture. So why isn’t he famous?

Because while he pioneered the technology, Farnsworth wasn’t able to make a commercial success of it. That fell to others, most notably David Sarnoff and RCA. They got rich off of television while Farnsworth died in 1971, alcoholic and in debt, largely forgotten.

Estes Kefauver had a lot in common with Farnsworth (including an unusual name). On one hand, the small screen made Kefauver into a household figure and earned him a reputation as a crusader for honesty and integrity in government. It’s highly unlikely that Kefauver would have been a contender for President in 1952 if not for television.

In the long run, though, Kefauver’s television exposure hurt him as much as it helped. His campaigning and speaking style didn’t lend itself well to TV, and his perpetually underfunded campaigns failed to capitalize on the medium the way other candidates did.

Ultimately, Kefauver’s relationship with television was similar to his relationship with the Presidential primaries: he was a pioneer, but because he didn’t make it all the way to the White House and was surpassed by those who came after him, his role has largely been lost to history.

Crime Does Pay… When It’s on TV

The Kefauver Committee hearings on organized crime were not planned as a televised spectacle. The committee traveled around the country to interview witnesses and gather facts, but there were no TV cameras in the hearings at first. It wasn’t until they reached New Orleans, eight months into the investigation, that a local station contacted the committee about the possibility of televising them.

The organized crime hearings weren’t the first Congressional hearings to be aired on television, either; that honor goes to a House subcommittee hearing on education which was held back in 1947. The crime probe did, however, mark the first time that a televised hearing captured the nation’s attention.

Why were the hearings such a hit? For one thing, they hit a sweet spot. In late 1950 and early 1951, many Americans had access to television for the first time, if not in their own homes then in a neighbor’s or at a local bar or movie theater.

At the same time, TV programming was still somewhat rudimentary; a lot of stations were desperate for compelling content, especially in the daytime. They could broadcast the hearings for hours at a time without drawing complaints from viewers angry about their favorite shows being bumped.

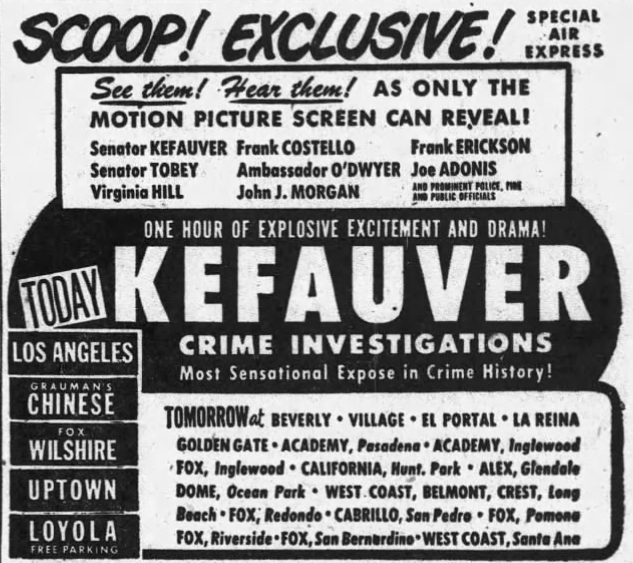

Even more important was the sensational subject matter. The hearings introduced Americans to a parade of crime bosses, corrupt politicians, and sleazy sheriffs, facing off against Kefauver and his fellow committee members. It was a classic good-vs.-evil showdown worthy of a Hollywood movie.

Indeed, many theaters that showed the hearings advertised them as though they were feature films, with Kefauver and the crime bosses listed like movie stars. (It’s no surprise that a wave of films based on the hearings were released over the next several years.)

Americans found it all irresistible. At the height of the hoopla – the New York hearings in March 1951, featuring the grilling of Frank Costello – over 30 million Americans were tuned in. As Life magazine wrote, “The Senate investigation into interstate crime was almost the sole subject of national conversation.”

Even at the time, the hearings were not without controversy. In The Atlantic, former assistant Attorney General Thurman Arnold attacked the concept of televised hearings as an invitation to mob justice. Others criticized the ad sponsors of televised hearings (a practice Kefauver eventually banned).

In his book Crime in America discussing the hearings, Kefauver acknowledged that televised hearings had positive and negative aspects, but argued in favor of keeping the cameras. “A public hearing is a public hearing,” he wrote, “and to me it makes no sense to say that certain types of information-gathering agencies may be admitted but that television may not, simply because it lifts the voices and faces of the witnesses from the hearing rooms to the living rooms of the people of America.”

It’s not clear whether the hearings, despite the attention they received, had the effect that Kefauver hoped. He wanted the public to respond to the revelation of crime and corruption in American cities by rising up and demanding action. However, Congress did not pass most of the laws the Kefauver Committee recommended to address the issues they uncovered, at least not in the short term.

Whether or not the hearings achieved everything Kefauver wanted, they achieved something important for him personally. They made celebrities out of many of the figures involved, but perhaps Kefauver most of all. His patient but persistent questioning and his impartial administration of the hearings won America’s heart and made him, in the words of David Halberstam in The Fifties, “[t]he first political star of television.”

“Estes Kefauver came off as a sort of Southern Jimmy Stewart,” Halberstam wrote, “the lone citizen-politician who gets tired of the abuse of government and goes off on his own to do something about it.” To many Americans, he became a hero. A poll taken at the end of 1951 named Kefauver as one of America’s most admired men, up there with the Pope and Albert Einstein. Kefauver even won an Emmy as a result of his hearings, and he was a celebrity mystery guest on the TV show “What’s My Line?”

Americans had gotten to know Kefauver through his presence in their living rooms, and they liked what they saw. Did they like it enough to propel him all the way to the White House?

Kefauver Rides the “Television Beam,” Ike Takes the White House

When Kefauver ran for President in 1952, the media tended to overlook his distinguished service in the House and much of his (admittedly short) tenure in the Senate. They acted as though he was running solely on the basis of his television celebrity.

For instance, Life magazine claimed that Kefauver “seeks to ride a television beam into the White House” and dubbed him “the nation’s first serious dabbler in a new brand of political magic – the awesome power of TV.” Rather snidely, Life argued that “his one asset, thanks to his Senate Crime Inquiry, was a name as well advertised as the most popular soap chips – and with an aroma equally antiseptic.”

Life’s sister publication, Time, was equally dismissive when writing about Kefauver after his shocking defeat of President Truman in the New Hampshire primary. They called him “a kind of Senator Legend—half man, half fiction” and added that “if the shadows of the television screen have made him a conquering legend, Kefauver is not the one who is going to spoil the picture by turning on too many lights.” They begrudgingly acknowledged that “[p]erhaps New Hampshire proves that Truman is already treed on Kefauver’s television antenna.”

Time and Life weren’t the only ones to treat the Kefauver phenomenon as a creation of television. Puppeteer Bil Baird’s CBS show included depictions of the major candidates in the primaries. Dwight Eisenhower, for instance, was represented by a miliary hat. Robert Taft’s puppet was bald and wearing an outdated dark suit. Kefauver’s puppet was clad in buckskin and clutching a television camera.

Kefauver’s televised celebrity definitely gave him an introduction to voters, but he worked hard in the primaries to turn that introduction into votes. And he did it the old-fashioned way: by giving speeches, shaking hands, and traveling the country. His shoestring campaign could barely afford a staff, much less television airtime.

Kefauver rolled through the primaries, winning almost every one he entered. But as discussed here many times before, that wasn’t enough to secure the nomination in those days.

As the convention approached, the Kefauver campaign – doubtless understanding the party leaders’ resistance to his candidacy – were hoping that the convention being televised would again generate a groundswell of support for their man. An AP story from shortly before the convention stated that it was “clear the Kefauver backers are counting on television at the Democratic national convention to boom the Tennessean’s chances of victory.”

Sadly, the boom never happened; Adlai Stevenson walked away with the nomination.

If there was a candidate who benefitted from television in the 1952 campaign, it wasn’t Kefauver; it was Dwight Eisenhower. Ike’s campaign hired the Madison Avenue executive Rosser Reeves, who managed to transform Eisenhower from a wooden and somewhat crochety old man into a warm and avuncular made-for-TV star. Reeves worked with Roy Disney and others to create the famous “Ike for President” commercial:

Stevenson, naturally, was horrified by the idea; he preferred televised 30-minute speeches to one-minute spots. “This isn’t a soap opera,” he huffed. “This isn’t Ivory Soap versus Palmolive.” (Stevenson’s campaign would produce some one-minute spot, although they weren’t nearly as catchy as “Ike for President.”)

Eisenhower, of course, rolled to victory. The role that Madison Avenue’s campaign for him played in that victory can be debated. But it was an example of the point: although Kefauver was a pioneer of the use of TV in politics, he wasn’t the one who reaped the biggest benefits.

The Dark Side of Televised Politics

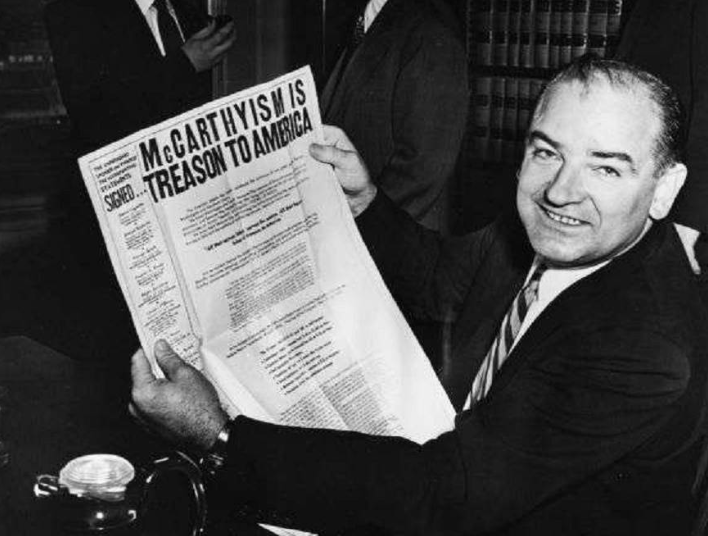

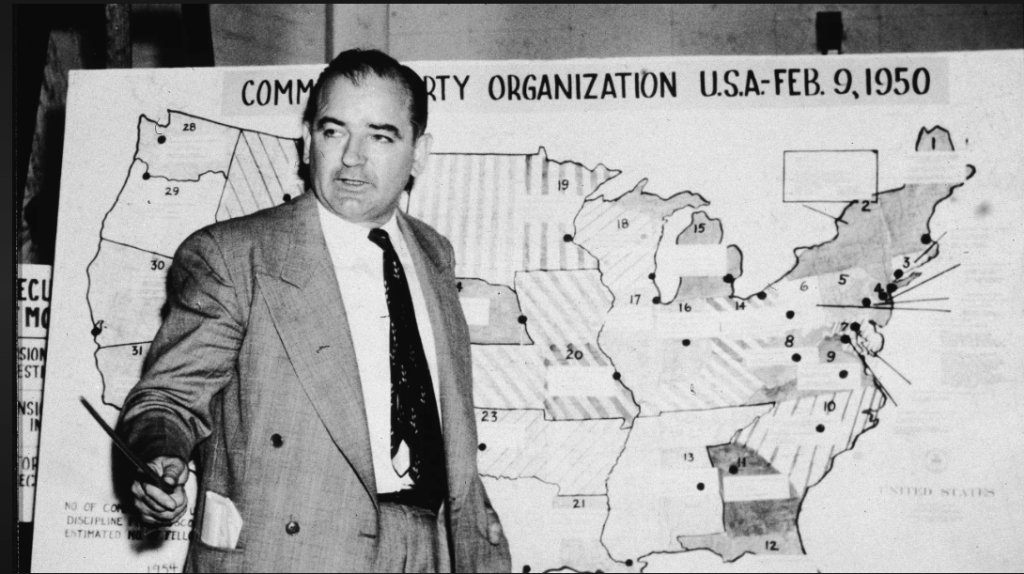

Of course, Kefauver and Eisenhower weren’t the only politicians making use of television during this era. There was also the infamous Senator Joseph R. McCarthy, who used television and other media to mount a public campaign of paranoia and trumped-up charges that the government was thoroughly infiltrated by Communists.

When the GOP gained control of the Senate after Eisenhower’s election, McCarthy became chair of the Committee on Government Operations. He used this perch to hold a series of hearings into alleged Communist infiltration of the Government Printing Office, the Army, and other government organizations.

Not only was McCarthy able to use TV to promote his wild and over-the-top charges, he and his acolytes were able to have a deep impact on the television industry itself. By threatening boycotts of companies that sponsored shows that featured supposed “subversives,” McCarthy-affiliated groups were able to effectively blacklist numerous actors, directors, and producers for their alleged Communist sympathies.

This ultimately came to a head during the Army-McCarthy hearings in the spring of 1954. Similar to Kefauver’s hearings on organized crime, these hearings were televised gavel-to-gavel, generating a similar public spectacle. This time, though, instead of the straightforward good-vs.-evil showdown of the crime hearings, viewers saw McCarthy and Roy Cohn flinging charges of Communism at the Army, who in returned accused McCarthy and co. of blackmail.

The hearings ultimately helped lead to McCarthy’s downfall, but they also helped sour Americans on the concept of televised public hearings. Kefauver had hoped the hearings would produce the sunshine-as-disinfectant approach, drawing the people’s attention to corruption and sparking a cry for change. But the McCarthy phenomenon showed that television could also be used by demagogues to promote inaccurate smears and foment widespread fear and paranoia.

I can’t help but think that the charges of demagoguery that were occasionally thrown at Kefauver, both at the time and in the decades since, stemmed in part from the backlash against McCarthy and the Red Scare. For some people, the memory of the crime hearings got tangled up with McCarthy’s war on Communism. That would happen even more often with the hearings Kefauver led next.

Kefauver Investigates TV… on TV

When Kefauver began gearing up for another Presidential run in 1956, he went back to the well, using television to boost his national profile. Assuming the chairmanship of the Senate’s juvenile delinquency subcommittee in January 1955, he hoped to turn it into another nationwide sensation like the organized crime probe of four years earlier.

While Kefauver’s juvenile delinquency investigation did indeed earn him more face time on television, it also looked at the dark side of the medium. Kefauver held a series of hearings aimed at determining whether TV was contributing to the surge in juvenile delinquency.

The subcommittee’s report on the subject noted that television “is gaining prominence over the radio, movies, the reading of magazine, newspaper and books,” especially among younger people, and that students spent as much time watching TV as they did in school. “Television is frequently the teacher,” the report concluded.

And what were the children learning? Subcommittee staffers surveyed TV shows during the hours when kids were most likely to watch, and didn’t like what they saw. “It was found that life is cheap; death, suffering, sadism, and brutality are subjects of callous indifference and that judges, lawyers, and law enforcement officers are too often dishonest, incompetent, and stupid,” the subcommittee reported.

What could be done about this? The subcommittee suggested that citizens’ groups maintain vigilance and advocate for more wholesome programming for children. They suggested more widespread adherence to the voluntary code of standards advocated by the National Association of Radio and Television Broadcasters (along with recommending some improvements to the code).

And although the subcommittee rejected all suggestions of government censorship of television, they did suggest that the FCC take TV stations’ compliance with broadcast standards into account when deciding whether to renew their broadcast licenses. “[T]hose conducting the mass media have a responsibility to exercise freedom of speech and press with due regard to the public welfare,” the subcommittee wrote in its report.

More TV Milestones, But No Victory

By the time Kefauver ran for President again in 1956, he had enough of an established reputation – and television was an established enough medium – that he was no longer treated as a creation of television. Unfortunately, his primary campaign had little more money this time than in 1952, so TV ads again weren’t in the budget.

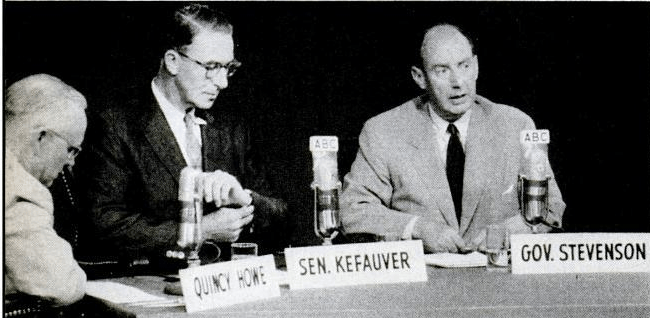

The 1956 primary did lead to one TV-related milestone: the first televised primary debate, between Stevenson and Kefauver from Miami on ABC. I recapped that debate on a previous post on this site.

The debate wasn’t particularly revealing, as Stevenson and Kefauver had similar views on the topics that were discussed, but it did begin a tradition that would flourish in the coming decades.

Kefauver was again denied the nomination in ’56, but he did become Stevenson’s running mate, and as such he appeared in several of Stevenson’s commercials. Stevenson begrudgingly agreed to work with a Madison Avenue agency this time around, and the campaign made a point of raising money specifically to run TV ads.

Sometimes Kefauver appeared alongside Stevenson in ads – as in this cringe-worthy commercial in which Stevenson tries to pretend he understands the problems of farmers – but more often he would appear in the “attack dog” mode that running mates often play.

For instance, he was featured in the “How’s That Again, General?” series of commercials, which features clips of Eisenhower’s promises from his ’52 campaign, followed by Kefauver explaining how Eisenhower abandoned or failed to live up to that promise while in office.

These commercials took advantage of Kefauver’s reputation as a truth-teller, as established back in the organized crime hearings. In each case, Kefauver used facts to bolster his case that Ike had in some way not lived up to his prior campaign rhetoric. (The commercials didn’t work, alas, as Eisenhower was re-elected in a landslide.

The True TV Candidate Arises

If you watched some of the Kefauver clips above, you probably noticed that he wasn’t a particularly telegenic personality. He came off as rather solemn and stiff when he was reading from a script; when speaking extemporaneously, he had a bad habit of serving up word salad and mixing up names.

Kefauver may have been the first politician to be prominently associated with television, but he was hardly a natural fit to the medium. Even Halberstam, who dubbed Kefauver “[t]he first political star of television,” fairly described him as “intelligent, shrewd, but also awkward and bumbling.” He had pioneered the use of television as a route to political fame, but America would have to wait for a politician who had the comfort and charisma to make the most of it.

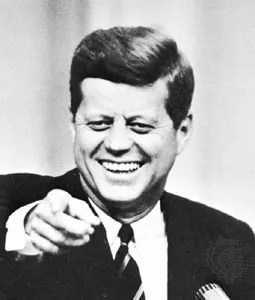

Someone like John F. Kennedy. The Senator from Massachusetts and television were made for one another. Even before he ran for President, JFK was a regular on shows like “Meet the Press” and “Face the Nation.” During the 1960 election, he famously won the televised debates with Richard Nixon in part became he looked relaxed and comfortable on camera while Nixon looked haggard and sweaty. Once in office, JFK was the first president to conduct live televised press conferences.

Even though some of his advisors worried that he might screw up, Kennedy correctly gambled that voters would react well to hearing the President’s unedited words and to his natural wit and charm. His first press conference attracted over 65 million views, and a 1961 poll revealed that 90% of respondents had watched at least one of his conferences.

Much of the myth of JFK was shaped by television. In the words of American Experience, “A skillful media manipulator, the new president used television to present a carefully constructed public image to Americans. Kennedy’s constituents saw him as vigorous, healthy, a dedicated husband, a giant among men. That he was none of these things did not matter. Americans viewed televised images of domestic harmony and regal splendor, and they believed what they saw.”

Veteran CBS broadcaster Bob Schieffer put it even more simply: “JFK was our first television president.”

He took the playbook that Kefauver pioneered and ran it to perfection. And because of that, he succeeded where Kefauver failed, and is remembered while Kefauver is largely forgotten.

Postscript: The Forgotten First

Being a pioneer is hard. You have to figure things out on the fly; there’s no example for you to follow. The risk of failure is huge. And you run the risk of incurring the wrath of people who are inherently suspicious of change. (Kefauver, for instance, developed an utterly unfair reputation as a shallow, demagogic publicity hound.)

And there’s always the risk that someone else will come along, follow in your footsteps, and reach heights that you never could. Frustratingly, these are often people who already have numerous advantages.

In Farnsworth’s case, RCA was a huge corporation with the resources to overwhelm the inventor. Kennedy, meanwhile, was rich, handsome, and from a politically powerful family. When Kefauver ran for President, he had to battle the hostility of Harry Truman and the Democratic power structure; by contrast, Kennedy had a virtual glide path to the Presidency.

It would have been easy for Farnsworth to grow embittered by the way things worked out. Fortunately, though, he was able to find some peace. His wife Pem recounted that when they watched the moon landing on TV, he turned to her and said, “Pem, this has made it all worthwhile.”

Similarly, Kefauver managed to make peace with his inability to reach the White House. After the 1956 campaign, he settled down to focus on his work in the Senate. In addition to earning the respect from his colleagues than had long eluded him, he had his most productive years as a Senator, including his landmark prescription drug bill. When Kennedy became President, Kefauver never begrudged him the success, and sought to work collaboratively with the administration.

And if his place in history isn’t quite what it should be… well, I’m working on that.

Leave a reply to All’s (Not) Fair in Politics and War: Kefauver Proposes a Congressional Code of Conduct – Estes Kefauver for President Cancel reply