One of the knocks on Estes Kefauver’s Senate career was that he garnered a lot of headlines, but didn’t have many legislative achievements. This isn’t really fair; he proposed plenty of laws to address the issues he uncovered in his hearings, but often couldn’t convince his colleagues to take action. Often he tried to warn them about potential dangers, but since they weren’t active crises at the time, his warnings were ignored.

A perfect case in point was the 25th Amendment to the Constitution, which specifies what happens when the President is unable to serve. Kefauver deserves to be remembered as a father of this amendment, but because he couldn’t get his colleagues to act on it before his death, his name is often written out of the story. It’s time to correct the record.

When the President Sneezes, America Catches a Cold

There’s a school of thought that treats the U.S. Constitution as something like holy scripture, and considers the Founding Fathers all-knowing wise men. In truth, while the Constitution is indeed a remarkable document, it had some holes and ambiguities.

Take the question of presidential succession. You’d think this was covered, since the Constitution provided for a Vice President to take over if something happened to the President. But what are the rules about when the Vice President takes over? Here’s the relevant passage from Article II, Section 1:

In Case of the Removal of the President from Office, or of his Death, Resignation, or Inability to discharge the Powers and Duties of the said Office, the Same shall devolve on the Vice President, and the Congress may by Law provide for the Case of Removal, Death, Resignation or Inability, both of the President and Vice President, declaring what Officer shall then act as President, and such Officer shall act accordingly, until the Disability be removed, or a President shall be elected.

Well, that clears it up. But wait a second: “the Same shall devolve on the Vice President…”? What exactly is “the Same”? Is it the “Office” itself (that is, the Presidency), or the “Powers and Duties” of the office? That is, does the Vice President become “Acting President” or the actual President? The language isn’t clear.

John Tyler answered the questions – sort of – in 1841. When William Henry Harrison died of pneumonia (and 19th-century medical care) a month into his term, Tyler took the oath of office, declared himself the President, and rebuffed all suggestions to the contrary.

In so doing, Tyler settled the question of the Vice President’s status in the case of a Presidential vacancy. Thereafter, whenever the President died or resigned his office, the Vice President was considered the President, without the word “acting” in his title.

Problem solved! But wait: what about that clause in Article II about “Inability to discharge”? Death and resignation are final; in those cases, the President isn’t coming back. But what if the President is just… sick? Too sick to perform his job duties, but still alive? What happens then?

In a situation like that, does the Vice President become the President, or just Acting President? When the President recovers from his illness, does he become the President again? And who decides when the President is too sick to do his job, or recovered enough to start doing it again?

Amazingly, America lived through not one, but two crises where the President was incapacitated for extended periods without managing to settle this question.

In 1881, James Garfield was shot by a lunatic office-seeker, but he lingered in a hospital bed for 80 days before dying (of 19th century medical care, mostly). During that time, he was largely unable to do his job.

What did the government do while Garfield was in his sickbed? Well… not much. Any business that didn’t require the President’s direction or approval continued. The Cabinet thought it might be a good idea for the Vice President to become Acting President, but they didn’t really trust VP Chester Arthur and they weren’t sure whether Garfield could legally become President again if he recovered, so they did… nothing. (Arthur became President when Garfield finally died.)

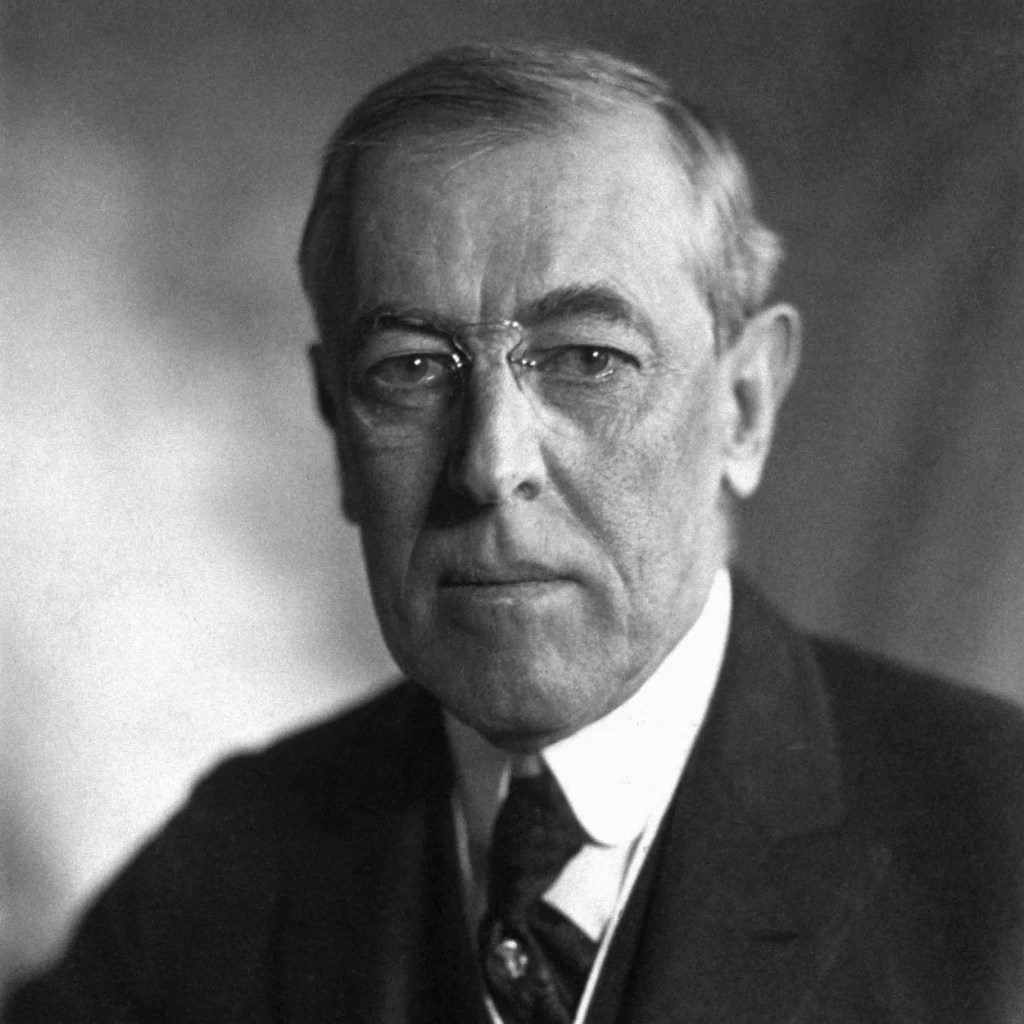

In 1919, Woodrow Wilson suffered a massive stroke while touring the nation to whip up support for his League of Nations proposal. For months, Wilson was bedridden and essentially incommunicado. In a scheme that sounds like a deleted scene from “Weekend at Bernie’s,” Wilson’s wife and doctors controlled all access to the President, going in to “consult” with him on critical matters but otherwise not letting people see or talk to him.

Again, the Cabinet and Vice President Thomas Marshall – with virtually no information about Wilson’s condition – were left to decide what to do. Secretary of State Robert Lansing took it on himself to organize Cabinet meetings; once Wilson “recovered” enough to leave his sickbed, he fired Lansing for disloyalty. And Wilson’s advisors didn’t really think Marshall was up to being President. So again, everybody did… nothing.

(There was also the time Grover Cleveland had secret cancer surgery on a yacht during his second term, but we won’t count that one since virtually no one knew about it at the time.)

After each of these incidents, there was a general agreement that we really needed to do something to fix this Constitutional loophole. But then… nothing.

At least until Estes Kefauver came along.

Kefauver’s Fix Gets Bogged Down in Details

Kefauver was no stranger to Constitutional loopholes. He spent much of his career trying to fix the issues that he spotted.

In 1940, the year after he joined the House, he proposed a bill to address a gap in the 20th Amendment, which changed the start and end dates for the terms of the President, Vice President, and members of Congress. The amendment left it up to Congress to determine who would be President if there was no President-elect or Vice President-elect on Inauguration Day (either because they both died, or the election was deadlocked and Congress hadn’t selected a winner).

Kefauver’s bill would have made the Speaker of the House (or in his absence, the President Pro Tem of the Senate) the temporary President. He introduced the bill five times; the House passed it in 1941, but the Senate never took action (Kefauver speculated later that was “because they wanted their man to come first”).

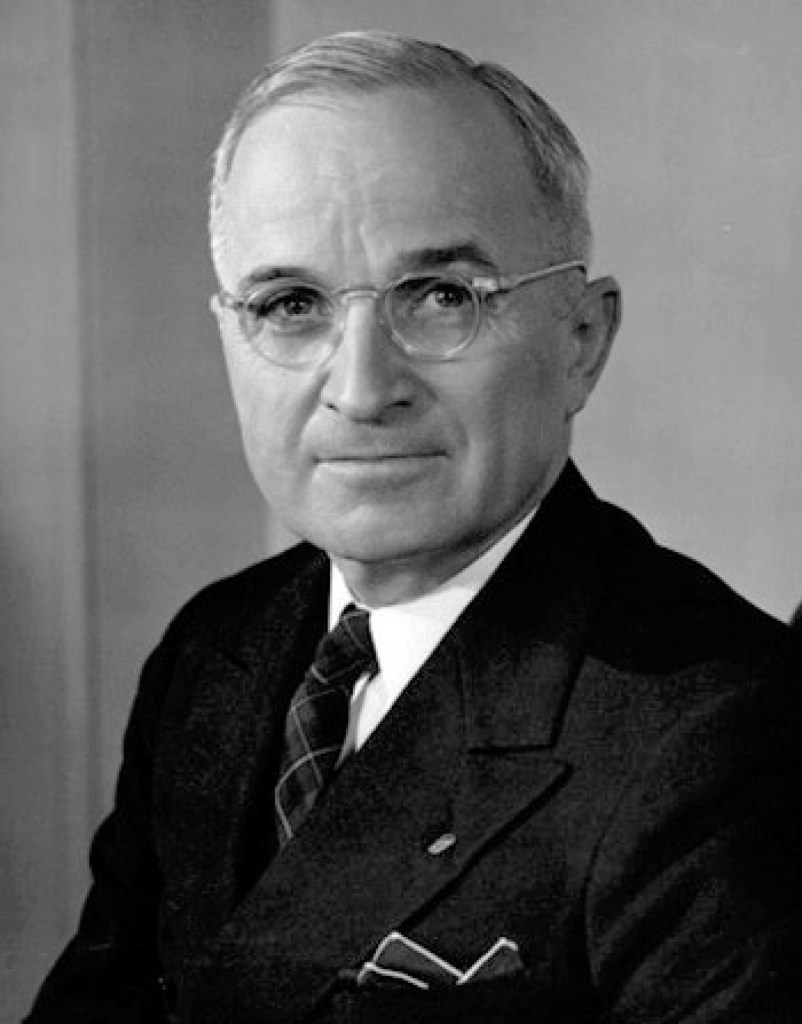

When Harry Truman assumed the Presidency after FDR’s death, he asked Congress to modify the line of presidential succession to make the Speaker and President Pro Tem third and fourth in line, respectively, ahead of the Cabinet secretaries. Kefauver introduced legislation to this effect in Congress, which eventually became the Presidential Succession Act of 1947.

In 1955, Kefauver proposed a Constitutional amendment to address the emergency functioning of Congress in case of, say, a nuclear strike on the Capitol. Kefauver’s amendment would have authorized state governor to appoint temporary members “on any date that the total number of vacancies… exceeds half the authorized membership.” Kefauver filed this amendment multiple times, but it was never adopted.

(When he filed the bill in 1959, other members attached amendments – one to give DC residents the right to vote in national elections, the other to abolish the poll tax in federal elections – that became the 23rd and 24th Amendments, respectively. Kefauver’s original bill, however, didn’t make it out of the House.)

During this period, the question of Presidential inability to serve reared its head due to Dwight Eisenhower’s somewhat frail health. His heart attack in February 1955 raised questions about his ability to run for a second term. He ran anyway and rolled to victory, but faced serious health challenges in his second term, including ileitis and a stroke.

To Eisenhower’s credit, he sought to address the matter by making an informal agreement with Vice President Richard Nixon. In the event that Ike was unable to serve, Nixon would serve as acting president until Ike declared himself well enough to resume his duties.

Kefauver, meanwhile, sought a more permanent solution. In 1958, he held hearings in his Senate Subcommittee on Constitutional Amendments to discuss the issue. These hearings built on similar hearings held a couple years earlier by his friend Rep. Emmanuel Cellar and the House Judiciary Committee. Kefauver’s subcommittee heard testimony and received memoranda and letters from numerous constitutional experts.

One witness, Attorney General William Rogers, endorsed a version of idea proposed by the previous AG, Herbert Brownell. Modeled on Eisenhower’s agreement with Nixon, the proposal was as follows:

- The Vice President would become Acting President if the President submitted a written statement that he was unable to perform his duties.

- If the President became ill before he could submit a written declaration, the Vice President could become Acting President with the consent of a majority of the Cabinet.

- In either case, the President would resume his duties once he submitted a written declaration that he had recovered.

- Alternatively, the Vice President could ask Congress to declare him Acting President, with approval of a majority of the Cabinet. If a majority of the House and 2/3 of the Senate agreed, the Vice President would serve as Acting President for the remainder of the term.

Rogers’ proposal was approved by Kefauver’s subcommittee in March 1958, but the Congress adjourned without taking action on the bill. They also failed to pass a bill in 1959 or 1960. This wasn’t they disagreed over the need for an amendment; instead, they couldn’t agree on the details, particularly on who would decide whether the President was unable to serve and whether he was recovered enough to resume office.

“I do not believe that the failure of Congress to approve a constitutional amendment…. is due to indifference or apathy,” Kefauver explained later. “It is due instead to disagreement and doubt as to the form which a constitutional amendment should take.”

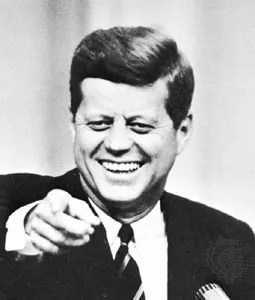

When John F. Kennedy succeeded Eisenhower in 1961, Congress’ concern for the issue waned. With a young and (seemingly) healthy President in office, the matter no longer seemed like a crisis, and they were ready to drop it.

Kefauver, however, implored his colleagues not to let it go. He continued to raise the issue for consideration, and he what he could to keep the issue in the public spotlight.

In 1962, Nebraska attorney and political scientist Richard Hansen wrote a book entitled “The Year We Had No President,” highlighting the issue and historical instances (including the Garfield and Wilson examples) where it came into play. Kefauver wrote the book’s foreword.

“The subject of this book is as important as the office of the United States Presidency itself,” Kefauver wrote. “The demands of the nuclear age upon the office of President require that the discharge of its duties never be in suspension or uncertainty.”

In June 1963, Kefauver and New York Senator Kenneth Keating, who had sponsored competing versions of the amendment, joined forces and submitted a revised bill. To head off debates over details, the Kefauver/Keating amendment left it up to Congress to enact legislation to determine how the beginning and end of the President’s period of inability would be determined, as well as what to do in the scenario that the President and VP were simultaneously unable to serve.

To drum up interest in the amendment, Kefauver held another round of subcommittee hearing. Seven witnesses, including Deputy AG Nicholas Katzenbach, spoke in favor of the proposal.

Kefauver urged his colleagues to act now. “[T]he essence of statesmanship is to act in advance to eliminate situations of potential danger,” he said, urging Congress to “take advantage of our present good fortune to prepare now for the possible crises of the future!”

Unfortunately, Kefauver’s unexpected death in August brought progress to a halt. But just three months later, another unexpected death would get things going again.

Assassination Sparks Action, Finally

Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963 shocked the world, and reminded Congress of the importance of closing this loophole. “As distasteful as it is to entertain the thought,” Keating noted, “a matter of inches spelled the difference between the painless death of John F. Kennedy and the possibility of his permanent incapacity to exercise the duties of the highest office of the land.”

Indiana Senator Birch Bayh took over leadership of Kefauver’s subcommittee on Constitutional amendments (rescuing it from elimination by Judiciary Committee chair James Eastland). He held yet another set of hearings in the beginning of 1964. “Here we have a constitutional gap – a blind spot, if you will,” Bayh said. “We must fill this gap if we are to protect our Nation from the possibility of floundering in the sea of public confusion and uncertainty.”

Meanwhile, the American Bar Association held a conference to consider the issue in January, and issued their proposal the following month. Bayh’s subcommittee reported out a bill based on the ABA’s recommendations in May, and the Judiciary Committee unanimously approved it in August. But the House took no action, and the bill died at the end of session.

Bayh tried again in 1965, with Cellar filing a companion bill in the House. Lyndon Johnson sent a special message to Congress that January asking them to take action.

The Senate acting quickly, approving the bill (with minor changes) unanimously in February. At the same time, the House Judiciary Committee held hearings. By April, they’d moved it to the House floor.

Cellar urged his colleagues to approve the amendment, calling it a “well-rounded, sensible, and efficient approach toward a solution of a perplexing problem – a problem that has baffled us for over 100 years.”

House Speaker John McCormack revealed that after Kennedy’s assassination, he’d signed an agreement with Johnson similar to the one Eisenhower signed with Nixon. He acknowledged that it was “outside the law,” but called it “the only thing that could be done under the circumstances, when we do not have a disability law in relation to the President in existence.”

“We cannot legislate for every human consideration that might occur in the future,” McCormack said. “All we can do is the best that we can under the circumstances.”

The House passed the amendment overwhelmingly.

The amendment then moved to conference committee to resolve differences between the House and Senate versions. The committee deadlocked for two months over the question of how to proceed in the event there was a challenge to the President’s declaration that he was fit to resume office. They ultimately compromised, giving the Vice President and Cabinet 4 days to submit a challenge to a Presidential declaration of recovery, mandating that Congress convene within 48 hours to consider the challenge, and then giving them 21 days to decide the question.

The House approved the conference report on the last day of June 1965, with the Senate approving it a couple days later after a debate. It then went to the states for ratification, finally becoming law when Nevada became the 38th state to approve on February 10, 1967.

“It was 180 years ago, in the closing days of the Constitutional Convention, that the Founding Fathers debated the question of Presidential disability,” said Johnson upon the amendment’s ratification. “It is hard to believe that until last week our Constitution provided no clear answer. Now, at last, the 25th amendment clarifies the crucial clause that provides for succession to the Presidency and for filling a Vice Presidential vacancy.”

It is indeed hard to believe that it took almost two centuries for the country to settle this important question. But thanks in large part to Kefauver’s tireless efforts over many years, we finally reached a solution.

This gets back to my original point. Kefauver often trod a lonely road in the Senate, trying desperately to get his colleagues to act on issues he saw as important. But because they weren’t active fires, his pleas often fell on deaf ears. We’d be better off as a country if, as Kefauver said, our leaders thought like statesmen and fixed issues before they became crises. By then, it’s often too late.

Leave a reply to Duck and Cover: America’s Troubled History with Civil Defense – Estes Kefauver for President Cancel reply