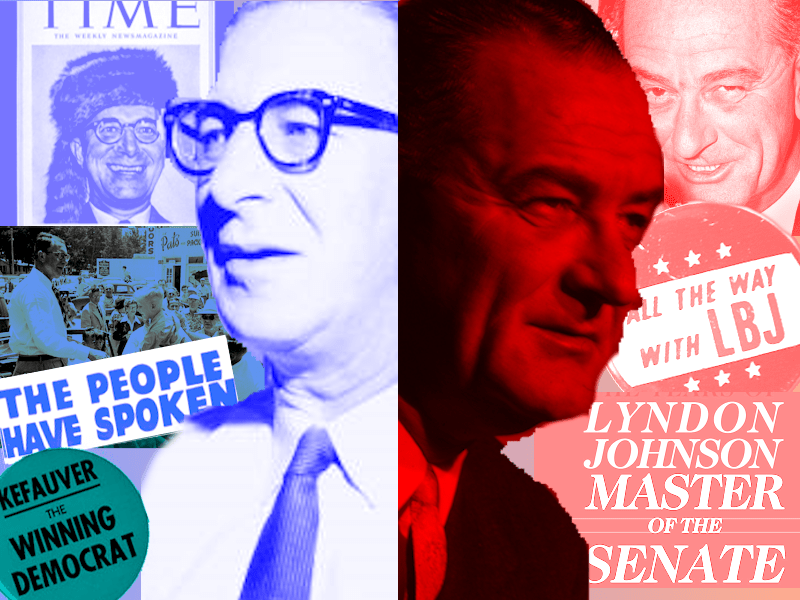

Estes Kefauver and Lyndon Johnson both entered the Senate in the same year, 1948. Both were ambitious Southerners who craved higher office. Both were more liberal than most of the Southern colleagues, particularly on civil rights issues. And yet Johnson quickly rocketed to the top of the Senate power structure, ultimately becoming Vice President and then President, while Kefauver remained a perpetual outsider for most of his Senate tenure and found his aspirations for higher office opposed by Democratic power brokers at every turn. Why the difference?

I’m not the only one to ponder this question. Kefauver himself wondered the same thing. For instance, when Kefauver refused to sign the pro-segregation Southern Manifesto, he was denounced as a traitor by his regional colleagues, while Johnson was not similarly castigated for doing the same thing. “How does Lyndon do it?” Kefauver once mused to adviser A. Bradley Eben.

The answer reveals a lot about the two men’s very different approach to politics.

Kefauver biographer Charles Fontenay answered the question this way: “Lyndon ‘did it’ by wooing the good will of the senators as assiduously as Kefauver wooed that of the voters.” Johnson was the ultimate insider: he sought to learn the unwritten rules of whatever situation he was in, then quickly used them to his advantage. Kefauver insisted on playing by the rules as they were written; the idea that there might be a separate set of unwritten rules seemed to offend him. As Fontenay put it, “Kefauver [was] always as wrapped in the mystique of abstract principle – the equality of men under the law, the equality of senators under the rules – as Johnson was devoted to pragmatism.”

While Johnson took the insider’s route to power, Kefauver took the outsider’s route, making his case directly to the voters as he criss-crossed the country, driving himself to exhaustion to shake every hand that he could. This made Kefauver one of the most popular and admired Senators in the country, but because he didn’t play by the unwritten rules that Johnson mastered, he remained relatively unpopular with his colleagues. As LBJ aide Harry McPherson wrote in his memoir, “Power outside the Senate did not follow from power within, and vice versa. Neither popular favor or significance in the national party flowed from a senator’s ability to move a bill. Indeed there were times when they seemed mutually exclusive.”

Kefauver’s pursuit of the organized crime probe was a case study in the strengths and weaknesses of in his approach to politics. Tasked with examining the influence of organized crime on American cities, Kefauver diligently did so. He promised to run a “no stones unturned, no holds barred, right down the middle of the road, let the chips fall where they may” investigation, and he did exactly that. In doing so, he won the hearts of voters across the country and made himself into a national figure.

However, when Kefauver was placed in charge of the crime subcommittee, there was an unwritten instruction attached: Whatever you do, don’t embarrass the Democratic Party in advance of the 1950 midterm election. Not only did Kefauver not obey this instruction, he seemed completely oblivious to its existence. Two of the first cities where he turned up evidence of high-level political corruption were Chicago (which led to him being blamed for the defeat of Majority Leader Scott Lucas, who was from Illinois) and Kansas City (which earned him the permanent enmity of President Truman, who was a product of KC’s political machine).

If LBJ had run the crime investigation, it would have gone very differently. He would have focused on the handful of Republican machines in existence in places like Philadelphia and Cincinnati, and would have steered well clear of Chicago and Kansas City, unless he had the chance to embarrass Democratic opponents. Likely, he would have done his best to wrap the probe up quickly. In short, it would likely have been a far less extensive and meaningful investigation. But it would have enhanced his standing with Democratic leaders, even if it failed to register with the people.

Another example of the difference between Johnson and Kefauver is the way each man dealt with Texas Governor Allen Shivers. Johnson was perfectly happy to align with the conservative Shivercrat faction of Democrats in order to get elected to the Senate, and he was just as happy to turn his back on them and push them out of the party when they became a drag on his national ambitions. Kefauver, meanwhile, refused to tell Shivers that he would consider a bill to allow states to control offshore oil drilling in exchange for the delegates that might have won him the 1952 Presidential nomination. (More on that story here.) Kefauver wouldn’t bend on his principles, even for a shot at his greatest dream. LBJ was much more willing to be flexible on both principles and ideologies in his quest for power.

In addition, Johnson dabbled freely in the darker political arts. He worked with shady operators like Bobby Baker, folks who weren’t afraid to use bribes to buy votes, who knew which politicians had a weakness for alcohol or women and manipulated them accordingly. Not only did Kefauver not work with staffers like that, he would have fired anyone on his staff who behaved that way. Instead, Kefauver hired staffers who scoured the local Tennessee papers for graduation announcements and obituaries so that he could send out congratulations and condolence letters. Again, Kefauver’s mode of operation made him very popular with the average voter, but not with his fellow Senators.

Given Johnson’s adeptness at playing the inside game in the Senate, it’s no surprise that he quickly rocketed into a leadership position, becoming Democratic whip in 1951 and Minority Leader in 1953 (the most junior Senator ever to hold the position), taking over as Majority Leader two years later when the Democrats retook the Senate. And as he rose to power, he did his best to thwart Kefauver’s ambitions.

On some level, the reason for this was obvious: Kefauver was another ambitious Southern Democrat, and there was likely not enough room for both of them in a future Presidential race. But Johnson’s stated justification for blocking Kefauver was that he felt the Tennessean wasn’t enough of a team player.

When Kefauver applied for a spot on the Senate’s Democratic Policy Committee in January 1955, Johnson called Kefauver to tell him that the spot would go to someone else, saying, “I have never had the particular feeling that when I called up my first team and the chips were down that Kefauver felt he ought to be identified and ought to be on that team.” Kefauver’s frustrated reply: “Honestly, you never have given me a break since you have been the leader.”

When a spot opened up on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee the following year, Kefauver applied for the spot, only to be turned aside in favor of John F. Kennedy, who had four years less seniority. In response, Kefauver wrote Johnson an angry letter stating, “I am disappointed and feel I have been done very badly… I have tried, Lyndon, to cooperate with you and be helpful to you… Notwithstanding all of this, I have been turned aside on every request for Committees that I have made since you became the Democratic leader.” He went on to cite “rumors” that Johnson blocked his request in order to keep him for running for President in 1960.

(Ironically, Bobby Baker himself came to regret this decision. In a 1974 interview, Baker noted that JFK shirked his duties on the committee, and that “the one regret of my whole life is that we didn’t put Senator Kefauver on the Foreign Relations Committee,” calling it “a miscarriage of justice.”)

Naturally, when Kefauver decided not to run for President in 1960, focusing instead on his re-election as Senator, Johnson was all too happy to help. He gave Kefauver the plum Appropriations Committee spot that he sought, convinced Governor Frank Clement not to challenge Kefauver in the primary, and openly backed him against challenger Tip Taylor. In exchange, Kefauver supported Johnson’s unsuccessful Presidential bid.

It’s ironic how different someone’s legacy can look when you look at it through different lenses. When I watched the Kefauver-Stevenson debate from 1956, Kefauver came off as the practical, hard-nosed realist in comparison to Stevenson’s ivory-tower rhetoric and elitist insistence that there was no greater sin than openly seeking power. But when compared to LBJ, that Machiavellian insider operator, Kefauver’s insistence on principle and belief in the power of the people seems almost laughably naïve.

But that was Kefauver. He never quite fit in any group: not pure enough for the ideologues, too idealistic for the pragmatists, too independent for the party regulars, too moderate for Northern liberals, too liberal for Southern conservatives. He insisted on following his own path, even though it cost him the chance to achieve his highest goals. It’s why I find him such a fascinating figure – and why I admire him the way I do.

Leave a comment