Estes Kefauver’s record on civil rights for black Americans defies easy categorization. Certainly, by the standards of a Southern politician in the mid-20th century, he stood at the liberal end of the spectrum. Most of his fellow Southerners in Congress considered him a traitor to the South, an integrationist, or worse.

If you look at the highlights of his civil rights record – consistently opposing poll taxes, refusing to sign the Southern Manifesto calling for massive resistance to the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education, voting for the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960 – Kefauver looks as proudly liberal as he did on civil liberties.

Zoom in, though, and the picture gets murkier. Throughout his career he cast several votes, and made some statements, that aligned with his more segregationist colleagues. Unlike Kefauver’s clear and consistent record on the civil liberties of alleged Communist sympathizers, for instance, his record on issues related to black Americans is spottier.

If Kefauver wasn’t a clear champion on civil rights, then what was he? A fence-straddler? An opportunist? A hypocrite? Confused?

Let’s take a closer look at Kefauver’s history on civil rights first, and then try to make sense of it.

The Early Days: No on Poll Tax, No on Filibuster, Yes on Segregation

From the beginning of Kefauver’s House career, he opposed poll taxes, blasting them as “repugnant to democracy” and adding that they were “unreasonable, without foundation, and have nothing to do with the qualification of the voter.” As a Representative, he voted for anti-poll tax bills four separate times. He acknowledged that “voting for this bill is not politically expedient. I am only doing and saying what I think is right.”

He wasn’t quiet in his opposition, either. On the House floor in October 1942, he cast the abolition of poll taxes as a way to beat back fascism: “Today, we are trying to sell the representative form of government to people and nations throughout the world. To do that we must remove the shackles here at home. What a fine example we would be setting if now we would show the world our confidence in democratic processes and remove an obstacle which disenfranchises millions of American citizens.”

Also, one of the legislative reforms in his 1948 book A Twentieth Century Congress was the abolition of the filibuster, a popular tool used by Southern senators to block civil rights legislation. In the book, he describes the filibuster as “the most sacred cow on Capitol Hill” and calls for making cloture votes easier. Although he cast this recommendation primarily in the name of efficiency, he cited specific examples of filibusters used to oppose civil rights legislation.

While these positions were unusually progressive for a Southern politician of the era, Kefauver’s overall civil-rights record as a Congressman was mixed. He voted against a federal anti-lynching law, saying that state laws against murder were sufficient. He also voted against bills to make the Fair Employment Practices Commission – created during World War II to combat anti-black discrimination in defense and government jobs – permanent.

In addition, Kefauver made several public statements indicating that he was comfortable with segregation, if not outright in favor of it. “The Negroes of the South are not interested in [antisegregation] legislation,” Kefauver claimed before Congress in 1948. “They want schools, better economic opportunity, and houses. I hope their lot in these respects can be improved. It would not be in the interest of their own welfare to fan the fires of passion and disunity by espousal of Federal nonsegregaton laws.” As late as 1950, he publicly insisted, “I am opposed to abolishing segregation.”

“Winds of Freedom Are Blowing”: Kefauver Shifts Toward Integration

The Supreme Court upended the status quo on segregation in 1954 in Brown v. Board of Education, holding that segregating public schools based on race was unconstitutional. This ruling sparked a notable change in Kefauver’s civil rights stance as well. From that point forward, he would never again express support for segregation. Instead, he urged compliance with the ruling and for whites and blacks to come together at a local level to determine the path forward.

As Kefauver explained to the New York Post in 1956, “I think I’ve lived and developed with the problem in the last two or three years. I think it’s been apparent that segregation couldn’t be justified… Coming originally from the South, it takes a little time to adjust to those realities.”

The Brown v. Board decision dropped at a particularly challenging time for Kefauver, in the middle of his reelection campaign to the Senate. His primary opponent, Rep. Pat Sutton, attacked Kefauver as an integrationist. Despite Sutton’s attacks, Kefauver declined to criticize the Court or the decision. “I refuse to appeal to prejudice in connection with it,” he said of Brown v. Board.

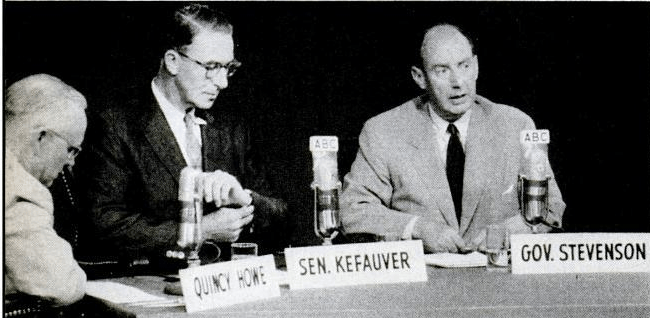

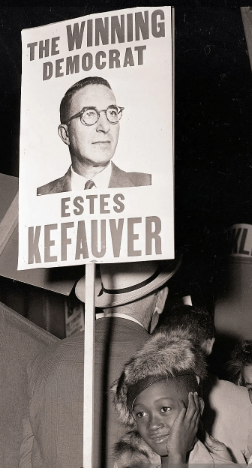

By the time of his second Presidential campaign in 1956, Kefauver’s civil rights views were indistinguishable from those of his prime opponent, Adlai Stevenson. If anything, Kefauver was more outspoken in support of civil rights, knowing that as a Southerner he was automatically suspect in the North.

“If I am elected,” Kefauver told voters on the campaign trail, “it will be my duty to uphold the Constitution of the United States, and the Supreme Court decision is the law of the land… You know and I know it’s ridiculous to say that a Supreme Court decision is unconstitutional.”

The infamous Southern Manifesto, calling for the reversal of Brown v. Board and condemning racial integration in public spaces, was written just as the ’56 primaries were heating up. Kefauver was one of only three Southern senators (along with his fellow Tennessean Albert Gore and Texas’ Lyndon Johnson) who refused to sign it.

“The Supreme Court decision is the law of the land,” Kefauver told Time magazine to explain his decision. “I could not sign or agree with the Southern manifesto; we cannot secede from the Supreme Court. The manifesto can only result in increasing bitterness and hard feelings and adding confusion to an already difficult situation.”

Perhaps his most eloquent statement came in a speech at Occidental College in April of that year, in which he tied black Americans’ struggle for civil rights to the fight against colonialism and oppression around the world:

Winds of freedom are blowing all over the world and everywhere men are demanding freedom and dignity. They are going to find the answer and they are going to find it in this generation. These winds are blowing in America just as they are blowing in Asia and Africa – everywhere.

When we in America have learned that all men in their own nation are due the full dignity of their humanity, are due the right to equal opportunity in the life of their nation for themselves and their children, then we can face the world with pride and confidence.

Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960

Kefauver’s rhetoric in his 1956 campaign set the stage for his votes on the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960. He demonstrated considerable political courage in voting for both of them. However, the positions he took during the negotiations on both bills were sometimes confusing to friends and enemies alike.

On the 1957 Act, Kefauver sponsored an amendment guaranteeing jury trials in criminal contempt cases for voting rights violations. This was anathema to many liberals, who (rightly) feared that Southern juries would refuse to convict those accused of violating the voting rights of black Americans. Kefauver, however, considered trial by jury to be a bedrock Constitutional right.

“If there is any imperfection in the jury system, it will not be corrected by doing away with and surrendering the right to trial by jury,” he noted. “The cure for any imperfection is a better appreciation of the responsibilities of government, of citizenship, and of education, and by a greater use of the right to vote, the ballot box approach.”

On other amendments aimed at weakening the Act, Kefauver voted with the liberals. And of course, he voted for the final bill, one of only five Southern Democratic senators to do so. “I thought it was a fair and just bill,” Kefauver said, “and I could not clear it with my conscience to vote against the right to vote.”

Shortly before President Eisenhower signed the 1957 Act into law, the nation was rocked by a showdown at Little Rock Central High School. Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus called out the National Guard to prevent a group of nine black students from entering the high school due to an alleged “imminent danger of tumult, riot and breach of peace.” After a tense multi-week standoff, Eisenhower federalized the Guard and sent the 101st Airborne Division to escort the black students into the school.

Kefauver, whose vision of integration revolved around patient collaboration, dialogue, and goodwill between the races, was horrified by the incident. He condemned both Faubus’ use of the National Guard and Eisenhower’s deployment of the Airborne troops. “I was distressed by the Little Rock situation,” the Senator wrote to a constituent. “It seems to me that mistakes were made by nearly everyone involved… [C]ertainly the use of troops is no final solution to problems of human relations.”

The debate over the Civil Rights Act of 1960 occurred during another re-election year for Kefauver, and he once again faced a segregationist challenger, Judge Andrew “Tip” Taylor. Facing heat at home, he took a couple of unexpected stances that allied him with arch-segregationists like Mississippi’s James Eastland.

Most notably, he sponsored an amendment allowing black plaintiffs in voting-rights cases to be cross-examined and permitting the voting registrar or his counsel to appear in the hearing. Again, the amendment was opposed strongly by liberals who feared that black voters would be intimidated out of filing voting rights complaints. For Kefauver, again, it was a matter of principle: specifically, the right of the accused to face his accuser. He stoutly defended the amendment on the floor of the Senate as a means to prevent a “star chamber hearing…. which would be repugnant to our judicial system of procedure.”

Ultimately, Kefauver again voted for the final bill, this time one of only four Southern Democratic senators to vote aye (joining Gore, Johnson, and Ralph Yarborough of Texas). Announcing his intent to vote for the Act, Kefauver said, “I shall do so because I believe it is reasonable, constructive, and morally right… I have always been of the opinion… that all qualified citizens – regardless of race or color – should have the right freely to register and vote. This bill strengthens that basic right, and its provisions on this subject are workable and fair.”

He stood behind his vote on the trail. Campaigning in his opponent’s hometown, Kefauver outlined the passages of the Act one by one, stopping after each to say, “Well, I’m for that. I think it’s right. Is there anyone in the audience who’s against it?” Each time he received applause. At a stop in Memphis, he vowed, “I shall continue to favor the expansion of the right to vote until every qualified citizen, regardless of race, creed or color, is able to exercise his franchise.”

Making Sense of It All

So where did Kefauver really stand on civil rights? Was he a liberal at heart, who cast just enough conservative votes to placate the folks back home in Tennessee? (Or, in the less charitable framing of his Southern enemies, a race traitor who voted the other way occasionally to try and cover his tracks?) Was he (in a charge so often thrown at him on many issues) an opportunist, tacking with the wind and trying to craft a record conservative enough for Tennessee and liberal enough for his Presidential runs?

In my view, none of those narratives fits quite right. Certainly, Kefauver’s comments in support of segregation prior to Brown v. Board put the lie to the idea that he was a pure liberal on the issue. At the same time, Kefauver’s votes in support of black civil rights were costly enough – both in terms of support in Tennessee and among his fellow Southerners in Congress – that he wouldn’t have cast them if he didn’t really believe in them.

As for the charge of opportunism: his votes for the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and – especially – 1960 didn’t benefit him politically. By 1960, Kefauver knew that his hopes of winning the Presidency were over. Facing a tough primary challenge in Tennessee in 1960, it would have been easy for him to vote no and blunt the charge that he was an integrationist. (As an example, look at Gore, whose otherwise solid record on civil rights was blemished by his vote against the Civil Rights Act of 1964 – which came during his re-election campaign.)

Rather, Kefauver’s views on civil rights were complicated but based on several bedrock principles. And his complex and sometimes conflicting voting record on civil rights issues represented his honest attempt to balance those principles. While he assuredly kept an eye on political considerations – he was, after all, a politician – he also remained true to his beliefs.

Chief among those beliefs was his commitment to equal rights and protection for all Americans under the law. Throughout his career, Kefauver opposed laws that singled out a group of Americans for discriminatory treatment, whether those were poll taxes or limits on the free speech rights of Communists.

Relatedly, Kefauver was a firm believer in the rule of law, arguably to a fault. When he said that he “could not sign or agree with” the Southern Manifesto, he meant it literally; whatever his personal feelings about the Brown v. Board decision may have been, he recognized it as settled law and was not going to support any scheme to defy the Court’s decision.

At the same time, he was not going to support any civil-rights solution that he saw as creating shortcuts or workarounds to the American criminal justice system, even if those workarounds would lead to more black Americans being able to exercise their right to vote. Although Kefauver understood the reality of Southern racism, he didn’t believe that the solution was to change the system to reduce the opportunities for racism to drive unfair decisions; rather, he believed that the right approach was to trust in the fairness of our approach to criminal justice and to appeal to the better angels of Southern whites and persuade them to follow the law.

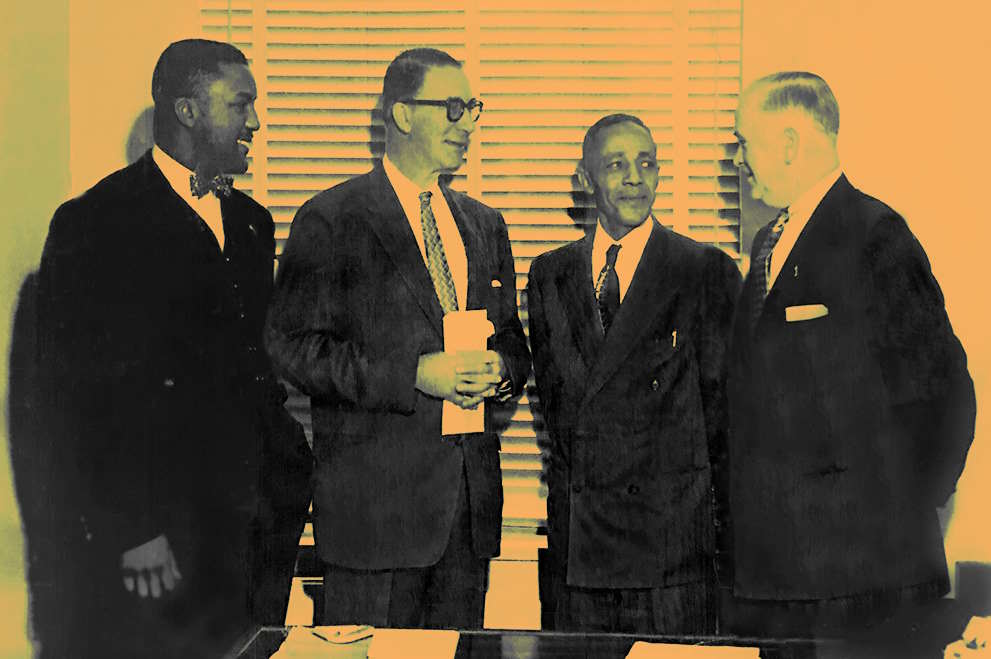

This was also consistent with Kefauver’s deep and abiding faith in the people. His frequent appeals for “intelligent people of both races” to come together in good will to figure out the path toward integration weren’t just rhetoric; he believed it. Back during the crime hearings in the early ‘50s, Kefauver justified his hearings by saying, “There is nothing the American people cannot overcome if they know the facts.” His approach to civil rights was consistent with this belief.

Kefauver didn’t believe that Southern whites could be forced to accept integration against their will, whether that meant Federal troops escorting black students into school or laws that cut racist juries and registrars out of the justice system. But he also believed that Southern whites weren’t irredeemable, and that their racism wasn’t intractable; with patience, education, and dialogue, they could be persuaded to give up their support for segregation, as he himself had been.

Lessons for Today’s Culture War

From a modern-day vantage point, there is plenty to criticize in Kefauver’s stance on civil rights. One could certainly argue that his faith in the people and in the impartial rule of law was naïve. And there’s no question that civil rights would have come much more slowly if we’d proceeded at the pace that he advocated.

That said, I believe his approach to this question holds important lessons for us even today. In our time, there are many cultural and rights-based issues that are as divisive as civil rights for black Americans were in Kefauver’s day. For true believers on both sides of today’s cultural divides, there’s a lot of loose talk about revolution, massive systemic changes, “national divorce,” civil war, and other approaches that basically amount to either forcing one’s preferred vision of the future on unwilling opponents or cutting the opponents out of the picture entirely by splitting the country in pieces.

If Estes Kefauver were alive today, I’m certain he would reject those approaches. He’d remind us that America – both the idea of it and the country itself, as a united whole – is a treasure worth preserving. He’d remind us that the right to vote, and the right to a trial before a jury of our peers, are hard-won treasures that we should not sacrifice.

And he’d encourage people on both sides of the cultural chasm to drop their ideas of revolution or crushing their opponents and to keep talking, in good faith and with good will, to figure out the way forward. It may not be the easiest approach, but it’s the one that’s true to the principles on which America was founded.

Leave a comment