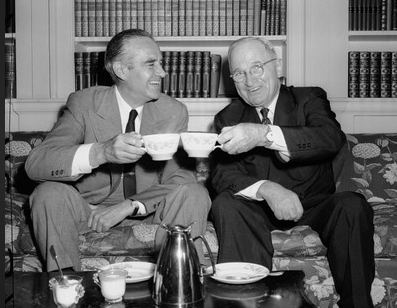

(featured image source: Life Magazine archive)

Practically from the moment that Estes Kefauver was denied the Presidential nomination at the 1952 Democratic convention, he had his eyes set on running again in 1956.

As early as the summer of 1955, while Kefauver was still downplaying any interest in making the race, Time magazine noted that “Estes has put his well-manicured Tennessee hand into a whole fistful of investigations,” including his juvenile delinquency hearings and his crusade against the TVA Dixon-Yates power deal. The article added, “Among Washington’s politicians and pundits there is no doubt about what Estes Kefauver is up to. He is running hard for his party’s presidential nomination in 1960… It does not mean that he would turn down the nomination in 1956, if it should happen to come his way.”

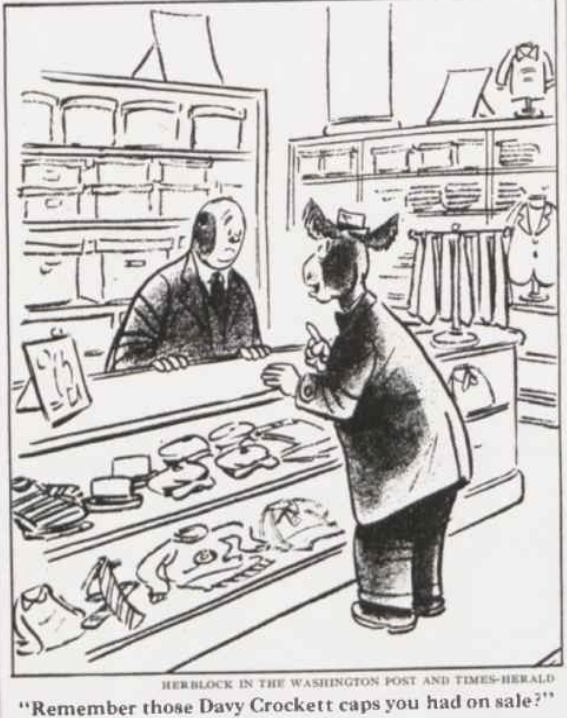

Coonskin Cap Back in the Ring

In the autumn of ’55, Kefauver began consulting with friends and advisers about whether he should run the following year. “I think I still have one good race in me,” he told a friend and supporter, “and I think maybe I ought to make it now.”

He realized, however, that there were a couple major obstacles in his path. First of all, incumbent President Dwight Eisenhower was hugely popular and would be extremely difficult to beat. However, there was some speculation that the 64-year-old Eisenhower might not run again. He’d been dropping references to the upcoming new generation of Republican leaders in his speeches. The heart attack he suffered in September of that year only fueled the rumors.

The Democratic nomination would be no cakewalk either. Despite his loss to Eisenhower in 1952, Adlai Stevenson had captured the hearts of party leaders, and the nomination was considered to be his for the taking, if he wanted it. Still the outsider among party regulars despite his loyal campaigning for Democratic candidates in ’52 and ’54, Kefauver knew that the only way to get the party to “come around” would be to “show them I’m the best vote-getter… They’ll take me if they think I’m the one they can win with.”

Kefauver faced another, more surprising opponent to his campaign: his family. The Kefauvers had four children by this point, and had just moved into a new home. Nancy Kefauver, who had campaigned vigorously with her husband to widespread acclaim in ’52, was adamantly opposed to the idea this time around, saying, “The children need me at home.” His children – especially his oldest daughter, Lynda – were also against the idea of their father spending all that time away from home on the campaign trail.

Given all the obstacles in his path, it might have made sense for Kefauver to take a pass and give it another try in 1960. But in the end, he decided that he couldn’t wait. On December 16, 1955, he threw his coonskin cap in the ring again (literally; he brought one with him to the announcement and threw it in the air for the photographers).

“The future of free men – your and my children – depends on how wisely and charitably we now apply the knowledge of the past to the problems of the future.” Kefauver said in explaining his decision to run. “I believe that the great experiment which our forefathers began has a potential for human good which even we can barely grasp.”

Nancy remained a dissenting voice. “I don’t know why he wants it,” she told a New York Post reporter about her husband’s Presidential yearning. “I try to figure it out myself. He just seems to be driven by this idea. He’s not ambitious about anything else – money or material things. I think he’s always been aiming at a goal a little higher.”

Despite Nancy’s misgivings, despite his lengthy odds of grabbing the nomination from Stevenson and his even lengthier odds of toppling Eisenhower, Kefauver was back on the trail in pursuit of his Holy Grail.

Deja Vu in New Hampshire

Just as in ’52, the road to the nomination began in the New Hampshire primary. Kefauver still had plenty of support among the state’s voters from his campaign their four years earlier, but Stevenson had the support of the party organization – including Democratic National Committeeman Henry Sullivan, who had been in Kefauver’s camp the last time around.

Stevenson, who was still hoping to claim the nomination without a fight, declined to campaign in the Granite State, but ran an organized write-in campaign, hoping to stop the Kefauver bandwagon before it got started. But while Stevenson reposed in his ivory tower back in Illinois, Kefauver barnstormed the state, shaking hands and riding in dog sleds.

When the results came in, Kefauver crushed Stevenson by a 5-to-1 margin. The race for the nomination was on.

A Minnesota Miracle

The Minnesota primary was up next, a week after New Hampshire. Stevenson figured the Gopher State would be his firewall. He had the entire apparatus of the state’s Democratic-Farmer-Labor party on his side, including Governor Orville Freeman and Senator Hubert Humphrey (who hoped to be Stevenson’s running mate). The only Minnesota elected official who supported Kefauver was first-term Rep. Coya Knutson. And since Kefauver had skipped that primary in ’52, he didn’t have the built-up goodwill he’d accumulated in New Hampshire.

It looked like a no-win situation, and Kefauver’s campaign staffers advised him to duck the primary. But the candidate had different ideas: “We might just win,” Kefauver told his staff, “and if we do we’ve changed the entire pattern of the campaign.”

He visited cities and towns all over the state, accompanied by the “glow wagon,” a campaign truck with his name in neon lights on the sides along with the slogan “Let’s Pick a Democrat who Can Win!” His campaign style quickly made an impression; one local reporter wrote, “Kefauver spent only a few hours in this southern Minnesota town, and I’m certain we could elect him mayor tomorrow. And we are kind of particular who we pick for mayor.”

Stevenson knew that Kefauver’s campaign blitz was making inroads, but he still felt confident of victory. That is, until primary night, when Kefauver stunned the political world by winning the state with 57% of the vote. As populist North Dakota Senator William Langer crowed the next day: “The politicians met, and they were for Stevenson. The common people met yesterday, and they reversed the decision.”

The Minnesota result (followed by an easy Kefauver win in Wisconsin, which Stevenson didn’t even bother to contest) detonated a bomb in the race. Freeman and Humphrey, who were counting on being Stevenson delegates, were suddenly left without seats at the convention. (Kefauver graciously offered them both spots in his delegation.) And Stevenson’s status as the inevitable nominee was shattered. His lead over Kefauver in national polls shrank from 34 points in February to just six in April.

Meanwhile, Kefauver was getting a second look from the party regulars who were previously determined to ignore him. “Before New Hampshire, hardly anybody would speak to us,” said campaign manager Jiggs Donohue. “After New Hampshire we got a polite ‘How do you do.’ After Minnesota, they really acted as if they were happy to talk to us. Since the Wisconsin vote some people are so polite it’s embarrassing.”

The Atlantic echoed Donohue’s assessment. “Already one can hear some ‘Well, why not Estes?’ talk in Washington,” said one May article. “If the senator sweeps the remaining primaries against Stevenson the ‘Why not Estes?’ chorus may drown out the protesting voices.”

The Illinois governor’s hopes for a front-porch campaign were out the window. As future Senator Alan Cranston, then chair of the California Democratic Council, said of Stevenson: “Adlai cannot be a reluctant candidate this time; that’s like trying to be a virgin twice.” If he wanted the nomination, he’d have to take a page from Kefauver’s book and earn it out on the trail.

Taking It to the Streets – and the Skies

The next two showdowns took place on the coast; unfortunately, though, not the same coast. The Florida primary would be held on May 29, with the California primary occurring a week later. (Both candidates didn’t campaign actively in Oregon, occurring in the same timeframe, as a favor to Senator Wayne Morse, trying to win over Democratic voters after being elected twice before as a Republican.)

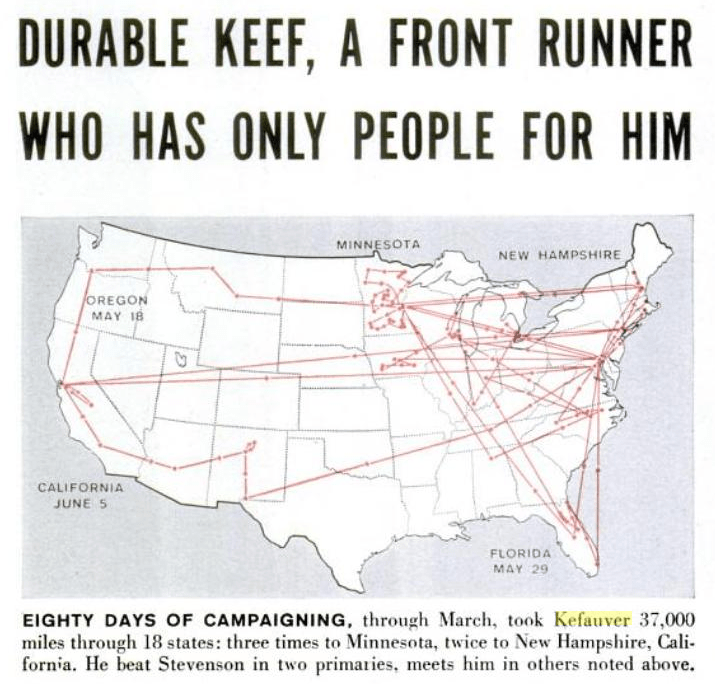

For Kefauver, this meant regular cross-country trips on top of his usual punishing campaign schedule. His typical campaign days began around 7 AM, followed by non-stop campaigning until 10 or 11 at night, after which he would often talk with supporters in his hotel until 3 in the morning.

Stevenson, meanwhile, was determined to match his rival stop-for-stop and handshake-for-handshake. The hilarious degree to which he hated having to campaign actively cannot be overstated. Facing a crowded room of reporters while preparing to go on TV in Los Angeles, he barked, “Do we have to have all the photographers here now?” In San Francisco, a voter pushed her young daughter into Stevenson’s arms and told her to kiss him; according to Time magazine, Stevenson “looked terribly embarrassed” at the scene. When reporters tried to get him to repeat the scene for their cameras, he snapped, “No! I’m not really in this kind of competition.” At one point, he got carried away with his determination to shake every hand, and wound up shaking the hand of a department-store mannequin.

But pushy photographers and strange children weren’t the only challenges the candidates had to face. Then as now, Florida and California were as far apart ideologically as they were geographically. This forced both Stevenson and Kefauver into uncomfortable straddles on the issues, particularly civil rights, to avoid upsetting voters in one state or the other. And since the candidates’ positions on most issues were largely identical, they were reduced to making a big deal out of small differences – or going negative and attacking each other personally.

The faceoff began amicably enough; Stevenson and Kefauver crossed paths in Florida, where they shook hands and pinned campaign buttons on each other’s lapels. But inevitably, the rhetoric of the campaign went downhill.

Stevenson objected to Kefauver’s characterization of him as the candidate of the party “bosses.” In return, he accused Kefauver of waffling on the issues (ignoring the fact that he was doing the same thing). Stevenson claimed that his positions “will not be changed to meet the opposition of a candidate who makes it sound in Illinois as though he opposed federal aid to segregated schools, in Florida as though he favors it, and in Minnesota as though he had not made up his mind.”

Kefauver initially tried to take the high road, saying “I have had only kind words to say about my competitors… I’m sorry Stevenson is putting the campaign on a personal basis.” But he couldn’t hold his tongue when ex-Florida Governor Millard Caldwell denounced Kefauver as an “integrationist” and a “sycophant for the Negro vote.” Stevenson, who spoke after Caldwell at the same event, did not denounce the remarks and later claimed he hadn’t heard them. An irritated Kefauver blasted Stevenson for what he called a “smear and smile” technique, which he likened to the infamous gutter-fighting campaign techniques of Richard Nixon.

Stevenson later got even more personal in a direct shot at Kefauver, calling him an absentee Senator. “There may be such a thing as wanting to be President too badly,” Stevenson charged. “And that may be one of the reasons why none of Senator Kefauver’s colleagues in the Senate has have endorsed him, and so few of the party’s leaders around the country.” It was a low blow, but an effective one.

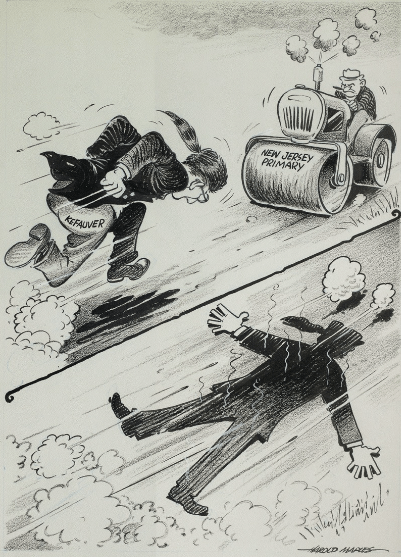

A Series of Unfortunate Events

Kefauver made a tactical error in April, choosing to actively campaign in the New Jersey primary, which Stevenson declined to contest. The problem was that the presidential preference vote was separate from the delegate vote, so Kefauver wound up getting almost all of the 122,000 votes cast in the preference ballot, but only received half a delegate from among the 26 delegates at stake. In short, it was a win on paper that looked like a loss.

When the Florida vote finally occurred, Stevenson won narrowly, by less than 15,000 votes among the 430,000 cast. The New York Times wrote that “neither [candidate] can justifiably claim victory” in the Sunshine State, and that “Mr. Kefauver did well, but not quite well enough.”

This only raised the stakes for the California primary, where Stevenson had again lined up prominent liberal supporters, including Eleanor Roosevelt and ex-Rep. Helen Gahagan Douglas. Kefauver had made some inroads with the black community due to his refusal to sign the Southern Manifesto, but he knew he was the underdog, and that a loss here would sink his chances.

At this point in the campaign, exhausted from the grueling round-the-clock campaign schedule and the coast-to-cost travel, and clearly feeling the weight of the Democratic establishment’s unyielding opposition to him, Kefauver got desperate.

He started launching uncharacteristically nasty attacks. He falsely accused Stevenson of vetoing an increase of old-age pensions as Governor. He claimed that “Stevenson made segregation the principal issue in Florida” and that the Illinois governor won there because “he was more suited to maintain the status quo of the South.” Campaign manager Donohue went even farther, claiming “a vote for Stevenson is a vote for [Mississippi Senator James] Eastland, [Georgia Governor Herman] Talmadge, [Louisiana Senator Allen] Ellender, and other white supremacist boys.”

The mudslinging wound up alienating a number of would-be supporters; even the Kefauver-friendly New Republic proclaimed itself “disheartened by this kind of attack.” Kefauver later apologized for the attacks, admitting, “I got mad and lost my head.”

Ultimately, though, it likely wouldn’t have mattered what Kefauver said. With all the prominent liberals in California behind him, Stevenson was in a strong position in the state, and he wound up scoring a huge win, rolling up almost 63% of the vote.

The End – and a New Beginning

The loss in California essentially killed Kefauver’s hopes of winning the nomination. Stevenson had rolled up more primary votes and more delegates, shattering Kefauver’s “Democrat who can win” argument.

But the California primary didn’t end the race. The mudslinging in Florida and California had taken some of the shine off Stevenson, and it just so happened there was an alternative waiting in the wings. New York Governor Averell Harriman, Kefauver’s old frenemy from the 1952 convention, had sat out the primaries. But with an endorsement from President Truman in his corner, he hoped to snatch the nomination at the convention, much as Stevenson had four years before.

Suddenly, Kefauver was once again a factor in the race. He didn’t have enough delegates to win, but he had enough to give a valuable boost to whomever he endorsed. Or, if he chose to keep fighting, he might just have enough support to deadlock the convention… and then who knows what might happen?

Harriman promised to retire Kefauver’s (substantial) campaign debt in exchange for his support. Stevenson offered to leave his VP choice open at the convention. Some members of Kefauver’s staff urged him to take Harriman’s deal; others urged him to work with Stevenson. Still others told him to take the fight all the way to the convention.

Kefauver agonized over the decision. “My people went through hell for me,” he moaned. “I can’t withdraw – they went through hell for me.” In the end, though, he couldn’t stand the idea of deadlocking the convention.

On July 31, he formally withdrew from the race and endorsed Stevenson. “I’ve got a lot of respect for a man who gets into the primaries and fights it out, as Adlai did,” he told reporters. “I couldn’t gang up to throw the nomination to someone who didn’t get into the primaries and make the race according to the American tradition.”

True to his principles, he didn’t take any of the deals offered to him, instead supporting Stevenson with no strings attached. And he worked faithfully to get his delegates to back Stevenson, calling personally to persuade the holdouts.

Kefauver’s Presidential quest was over. But his role in the 1956 election was just getting started.

Leave a reply to Give the Man a Hand! – Estes Kefauver for President Cancel reply