(featured image source: University’s of Tennessee’s Estes Kefauver Crime Collection)

On the rare occasions that Estes Kefauver is remembered today, his name most often comes up in connection with the televised hearings that he oversaw in 1950 and 1951 as chairman of the Senate Special Committee to Investigate Crime in Interstate Commerce. The hearings were a landmark moment in politics, and also for Kefauver himself. The hearings made him a household name (in the words of Life magazine, his was “a name as well advertised as the most popular soap chips”), a national hero, and a Presidential contender.

The Committee’s Beginnings

Given the way the hearings catapulted Kefauver to national fame, it’s little surprise that he was often accused of being motivated primarily by publicity, a charge that would dog him throughout his career. (The well-worn story is that Washington Post publisher Phillip Graham convinced an ambivalent Kefauver to sponsor the hearings by saying, “Don’t you want to be Vice President?”)

While it’s true that Kefauver hoped the crime investigation would garner public attention, crime and corruption were sincere concerns of his. The links between organized crime and politics, in particular, offended his strong sense of public ethics. As a House member in 1945, Kefauver was named chairman of a subcommittee that investigated federal Judge Albert Johnston of Pennsylvania. The probe, which prompted Johnston to resign, turned up connections to underworld figures. In the years that followed, Kefauver studied the reports of state crime commissions for evidence of criminal activity crossing state lines.

In response to these concerns, Kefauver introduced in January 1950 a resolution calling for an investigation “to determine whether… an organized syndicate operating in interstate commerce… is menacing the independence of free municipal governments, for the benefit of the criminal activities in the syndicate.” He noted that several big-city mayors had complained that they lacked the tools to combat organized crime effectively and had appealed to the Federal government for help.

To make his resolution reality, Kefauver had to overcome the resistance of the Judiciary Committee chairman, Pat McCarran of Nevada, who opposed the probe on Vegas-based grounds. The investigation then got caught in a turf war between the Judiciary and Interstate Commerce Committees. It wasn’t until May that the Senate authorized the committee’s formation; even then, Vice President Alben Barkley had to cast the tie-breaking vote. It wound up being a special committee staffed with members from both Judiciary and Interstate Commerce, with Kefauver as chairman.

The Committee

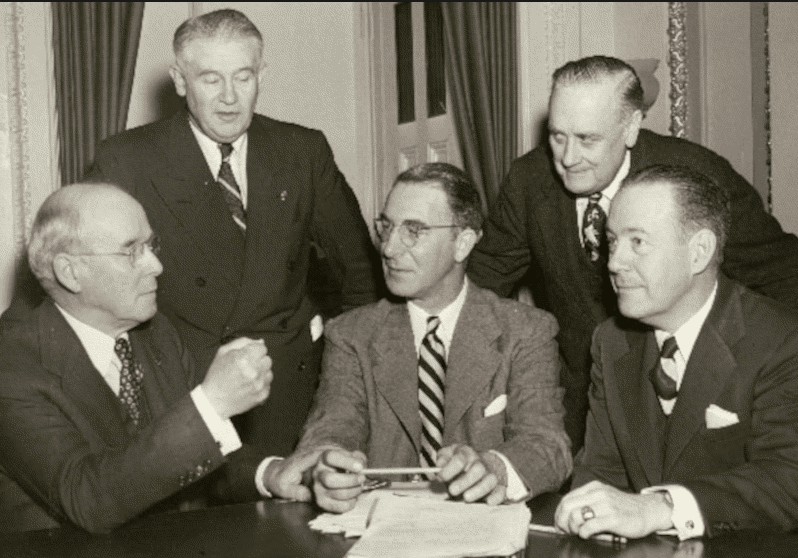

The special committee, popularly known as the “Kefauver Committee” or the “Crime Committee,” consisted of five total members, three Democrats and two Republicans.

Democrat Herbert O’Conor was a former State’s Attorney and Maryland Attorney General. Kefauver said that the Marylander’s “legal training and experience helped bring clarity to the shaping of many important decisions.” When Kefauver stepped down as chairman of the committee in May 1951, he tapped O’Conor to succeed him.

Republican Alexander Wiley of Wisconsin was leery of the committee at first, suspecting that they might attempt to bury or soft-pedal evidence of Democratic misdeeds. He quickly came around, though, impressed by Kefauver’s integrity and honesty. Kefauver wrote that “once [Wiley] became convinced that we had no partisan ax to grind, we had no stronger defender.”

Democrat Lester Hunt of Wyoming earned Kefauver’s praise for his “great gift for common sense and arriving at sound decisions.” Hunt ran the committee’s hearings in Tampa, which occurred around Christmas 1950. Kefauver skipped this hearing in order to spend time with his family; Hunt, meanwhile, was happy to go, because he got a free trip to Florida to watch the University of Wyoming play in the Gator Bowl a few days later.

The committee’s most colorful member was Republican Charles Tobey. The man Time dubbed “the seriously Christian Senator from New Hampshire,” provided hearty doses of moral outage. “Why don’t you resign?” he thundered at one corrupt sheriff. “I simply cannot sit and listen to this type of… political vermin who comes up before us and shoots off and defies the law.” Questioning a mobster at another hearing, Tobey called the mobster’s associated “a couple of rats” and erupted, “You know in your heart how crooked and rotten these things are. You ought to hate yourself for being in them.”

Tobey’s moral histrionics were counterbalanced by the committee’s chief counsel, Rudolph Halley. His just-the-facts manner and insistent questions, backed by carefully collected evidence, overmatched most of the witnesses who came before him.

And in the center of it all was the chairman, Kefauver, with his gentle Southern drawl, patient persistence, and quiet dignity. He approach the committee’s mission with his usual unflagging work ethic; he ran many of the early hearings as a committee of one, with staff assistance. His even-handed and impartial conduct of the hearings earned him widespread public praise. Journalist Sidney Shalett called Kefauver “the conscience of America,” while one admirer praised the Senator’s “quietly eloquent, almost Lincolnesque quality.”

The Hearings

The committee held its first hearing on May 26, 1950. It was the beginning of a nationwide odyssey that took them to 14 different cities from Miami to LA, from Chicago to New Orleans. Kefauver himself logged over 50,000 miles of travel on committee business. At those hearings, the committee heard the testimony of almost 800 witnesses in 92 separate days of hearings.

Through all of those hearings and all of that testimony, Kefauver aimed to reveal exactly how organized crime syndicates operated. Another key goal, believe it or not, was showing the American public that these syndicates existed. In our modern world of The Godfather, Goodfellas, and The Sopranos, it’s hard to envision a time when most Americans hadn’t heard of the Mafia. But in 1950, it was true.

Americans’ idea of organized crime in those days was represented by characters like Edward G. Robinson’s Johnny Rocco, the past-his-prime exiled gangster in the 1948 movie Key Largo, blustering vainly about Prohibition coming back someday and the gangs working together this time.

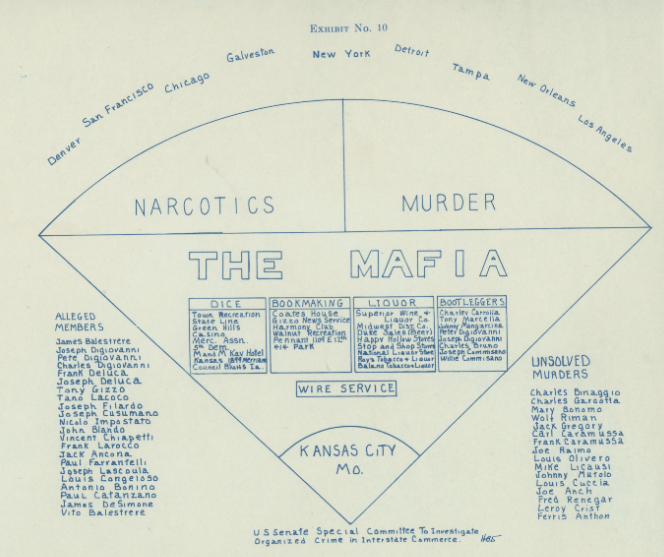

In reality, American crime syndicates were working together to a degree Rocco wouldn’t have imagined in his wildest dreams. As Kefauver wrote in his 1951 book Crime in America, the committee demonstrated the existence of “a loosely organized but cohesive coalition of autonomous crime ‘locals’ which work together for mutual profit.”

The committee patiently unearthed the tangled web of connections between gangs in various cities, illustrating the links with intricately detailed charts.

The hearings really captured the public imagination, though, by bringing America face-to-face with the modern mobster, showing that he was in some ways (and literally, in some cases) the guy next door. The “new aristocrats of the criminal world,” as Kefauver described them, weren’t ostentatious hot-tempered psychopaths like Johnny Rocco. Instead, they styled themselves as respectable businessman. In their March 1951 article on the hearings, Time described the typical criminal boss of the time like this:

His clothes are no longer flashy; everything’s gotta be in good taste. He is a homebody. He lives comfortably but not fabulously in a respectable neighborhood, contributes to charity, hobnobs with cafe society, is a friend to politicians, sends his children to summer camp and the big kids to college. He allows himself a Cadillac (usually registered in his wife’s name) and a home in Miami. He never, never carries a rod.

These gray-flannel gangsters weren’t sitting around pining for the return of Prohibition, either; they had found a perfectly lucrative replacement in gambling. Since the investigation was intended to have an interstate-commerce angle, the committee focused on the wire service that transmitted horse-racing results to bookies around the country. In the hearing, and in Crime in America, Kefauver declared the racing wire to be “Public Enemy Number One.”

The committee revealed the way that the Capone syndicate in Chicago muscled their way into control of Continental Press, the nation’s leading racing wire service; when previous owner James Ragen attempted to resist the takeover, he wound up dead.

The committee also revealed that the wire operators were savvy operators indeed. During World War II, a plane crash knocked out a vital telegraph circuit in California. The Fourth Army took about three hours to restore the circuit; Continental Press had their wire back up and running within 15 minutes.

Smile, You’re On Camera!

Arguably, the committee’s central achievement was bringing “the face of U.S. gangdom,” as Time called it, in front of the American people. Big-time gangsters like Meyer Lansky, Mickey Cohen, Tony Accardo, “Dandy Phil” Kastel, Carlos Marcello, and Joe Adonis testified before the committee. So did the corrupt sheriffs, police officers, and politicians who were in cahoots with the gangs. Some were congenial, some were belligerent, some were defiant – but in the end, they were brought low, faced with evidence of payoffs given and taken, taxes dodged, official duties shirked.

Their downfalls became national drama thanks to a relatively new innovation: television. In January 1951, a TV station in New Orleans telecast the entire hearings in the city. They proved a hit, and the public committee’s hearings from then on were fully televised. As the fervor grew, the networks – starved for daytime content – got in on the action. And the nation was hooked; Life magazine said that the hearings would “occupy a special place in history. The U.S. and the world had never experienced anything like it… There, in eerie half-light, looking at millions of small frosty screens, people sat as if charmed. For days on end and into the nights they watched with complete absorption.”

The audience for the hearings in New York and Washington was estimated at 20 to 30 million. Those who had TV sets at home tuned in; those who didn’t watched with neighbors or in bars. Even movie theaters started showing the hearings. An epidemic of delayed chores swept the nation; one woman wrote to Kefauver, “My husband started to repair a screen door at the noon recess, but was so interested in the broadcast, he did not finish the job yet. We watched the whole day.”

The highlight of the televised hearings was the showdown with Frank Costello, head of the New York mob, the man described by Chicago Crime Commission director Virgil Peterson as the “most influential underworld leader in America.”

Costello wound up testifying before the committee for seven days; he threatened to walk out on multiple occasions and actually did more than once, but returned later. At one point, the committee ordered the television cameras not to show his face; they focused instead on his hands. That was enough; his nervousness and agitation were apparent.

On the screen, the hearings played out as a classic showdown between good and evil. As David Halberstam wrote in The Fifties, “Estes Kefauver came off as a sort of Southern Jimmy Stewart, the lone citizen-politician who gets tired of the abuse of government and goes off on his ow n to do something about it.” Even the Television Academy took notice, awarding Kefauver a special achievement Emmy.

The Committee’s Impact

What was the ultimate impact of the crime hearings? The answer depends on how you measure it. The committee’s final report, issued in April 1951, made a total of 22 recommendations for laws to aid in combatting organized crime, the vast majority of which were not adopted. Kefauver’s call for a federal crime commission was ignored (J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI, who preferred to focus on chasing Communists, strongly opposed the idea). Only one law, expanding appropriations for the Narcotics Bureau, was passed as a direct result of the committee’s work. (Years later, though, Congress finally acted. In 1961, they passed the Federal Wire Act, criminalizing the use of the wire for sports betting. The RICO Act, which is frequently used to prosecute organized crime, was passed in 1970.) Suffice to say, the legislative legacy of the committee was slim.

But in other ways, the Kefauver Committee had a profound impact. Over 70 states and localities set up crime commissions in the wake of the hearings. Voters in Arizona, California, Massachusetts, and Montana, appalled by the committee’s findings, voted down referenda to legalize gambling in their states. Several of the gangsters who testified before the committee wound up in jail for tax evasion, contempt of Congress, and other crimes uncovered during their testimony. And the careers of many corrupt sheriffs and politicians were tarnished, if not ended altogether, due to the committee’s exposure of their misdeeds. Most notably, William O’Dwyer – former mayor of New York City and then Ambassador to Mexico – was grilled by the committee about his lax approach to prosecuting Murder, Inc. and his cozy relationship with Costello. He resigned his ambassadorship under pressure in 1952 and lived in virtual exile in Mexico for eight more years.

Perhaps the figure most dramatically impacted by the committee was Estes Kefauver himself. The televised hearings launched Kefauver to national stardom, something virtually unheard of for a freshman senator. Certainly, there’s no way he would have been a credible candidate for President in 1952 if not for his work on crime.

But the hearings were a double-edged sword for Kefauver; if anything, he and the committee did their jobs a bit too well. He ran a fair and impartial investigation, one that revealed considerable wrongdoing on the part of fellow Democrats. As a result, Kefauver earned several powerful enemies within the party.

Shortly before the 1950 election, the committee went to Chicago, where they questioned Dan “Tubbo” Gilbert, a police captain and candidate for Cook County sheriff. Gilbert admitted that he made thousands of dollars annually gambling on football games, boxing matches, and elections. Although Gilbert testified in closed session, a reporter secretly obtained and published a transcript of the testimony. Unsurprisingly, this sank Gilbert’s campaign for sheriff. It also sank the re-election bid of Scott Lucas, the Senate Majority Leader from Illinois. Lucas never forgave Kefauver for his defeat.

Florida Governor Fuller Warren, whose campaign was revealed by the committee to have been funded heavily by gambling interests, also became an implacable Kefauver opponents, calling him an “ambition-crazed Caesar” and a “shyster politician.”

The most dangerous enemy of all, though, was the incumbent President. Harry Truman was a known product of the Kansas City political machine. The committee turned up extensive ties between Kansas City politicians and organized crime. Kefauver painted a highly unflattering picture of KC in Crime in America, describing the city as “struggling out from under the rule of the law of the jungle.” Now add in the fact that the committee torpedoed O’Dwyer, Truman’s ambassador to Mexico.

Beyond the hit to Truman’s reputation, the President was a loyal party man, and he knew that revelations of urban corruption would hurt Democrats (who, then as now, were strongest in cities) generally. Though silent publicly, behind the scenes he worked harder than anyone to sink Kefauver’s Presidential ambitions.

In short, as a result of the crime hearings, the people loved Kefauver, but his fellow politicians hated him. This established a theme that would recur throughout his career.

Leave a reply to Kefauver at the Movies: “Turning Point” – Estes Kefauver for President Cancel reply