Originally, this post was supposed to cover an article Kefauver wrote for The Progressive magazine in 1948, making the case for major reforms to the Electoral College (a cause he championed throughout his career).

This post is not about that article. Why not? Because in the middle of it, Kefauver made a passing reference to an organized effort by Southerners to manipulate the Electoral College in the 1944 election. Wait, what?! Why hadn’t I heard of this before? (And why does there seem to be a pattern here?)

So I immediately dove straight into yet another research rabbit hole. Let’s talk about the attempted Electoral College revolt of 1944. Maybe I’ll get back to Kefauver’s article in The Progressive next week.

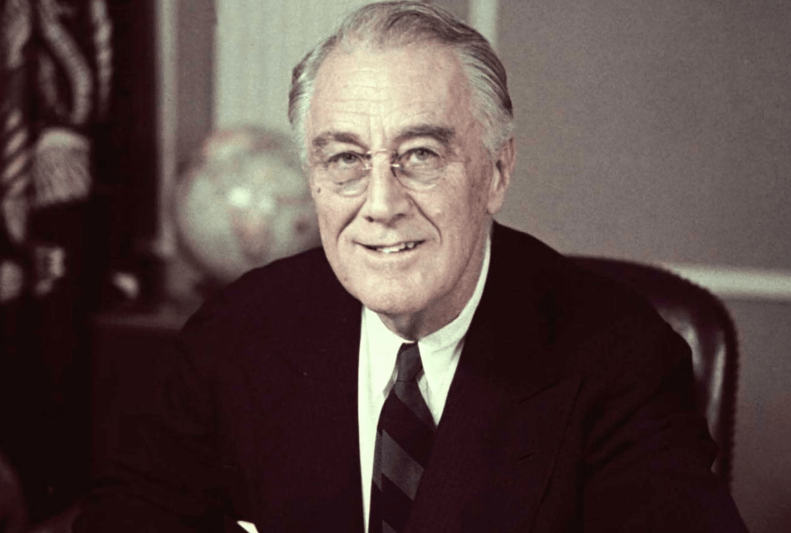

As FDR Tries for Four, Southern Storms Gather

Franklin Roosevelt is the only U.S. President ever to seek a fourth term. Despite knowing (but not publicly admitting) that he was in failing health, he was determined to see America through to victory in World War II. After playing coy for months, he officially declared for reelection in the summer of 1944.

The Democratic Party was all aboard the President’s reelection train. However, not everyone in the party was on board. Conservative Southern Democrats were increasingly opposed to both the New Deal and Roosevelt himself.

There were several reasons for this. For one thing, many Southern Democrats were opposed to FDR’s dramatic expansion of the federal government. Many of them focused on Vice President Henry Wallace as the symbol of what they saw as liberalism run amok.

The biggest issue, however, was civil rights. Northern whites were beginning to call for black Americans to receive equal treatment under the law, and Democratic leaders saw the possibility of making inroads with both black and liberal white voters. Even though Roosevelt’s record on the issue was mixed at best, Southern Democrats were beginning to realize that they no longer dominated the party, and they didn’t like it.

Two events early in 1944 stoked the furnace of Southern resentment.

One was a Congressional debate over a bill to enable soldiers serving overseas to vote. The original bill would have placed the federal government in charge of managing and distributing the ballots, and would have outlawed the collection of poll taxes or other state-level barriers to soldier voting.

Senate Minority Leader Robert Taft, believing that soldiers would vote overwhelmingly for FDR, kicked up a fuss over the poll-tax provision (ignoring the fact that Congress had passed a similar provision two years earlier) to woo Southern Democrats to his side.

Taft’s ploy succeeded, and Democratic Sen. Joe Guffey of Pennsylvania made things worse by accusing Southern Democrats of joining an “unholy alliance” with Republicans against the bill. In response, North Carolina Sen. Josiah Bailey warned Guffey that “we can form a Southern Democratic party and vote as we please in the Electoral College.”

The second event was the Supreme Court’s ruling in Smith vs. Allwright that states could not permit parties to hold segregated primaries. As most Democratic primaries in the South were open to whites only, the decision was deeply unpopular there.

In May 1944, signs emerged that the South might just take Bailey up on his threat. Unsurprisingly, the first move came from the Lone Star State.

The Eyes of Texas Are Upon You, Mr. President

The anti-New Deal Texas Democrats were organized by a wealthy Dallas businessman named E.B. Germany. He had the support of several state leaders, including former Gov. John Moody, Sen. W. Lee “Pappy” O’Daniel, and Rep. Martin Dies Jr.

This faction felt that they had lost control of the national Democratic Party to a collection of labor leaders, Communists, and black people. They demanded that the party return to its roots – specifically, white supremacy and states’ rights.

Germany’s group targeted the state Democratic convention in Austin on May 23rd, where the party was to select its delegates to the national convention and its slate of presidential electors.

On convention day, the anti-New Dealers had a majority. They voted to send a supposedly “uninstructed” delegation to Chicago. I say “supposedly” because, while they were not told which candidates to support for President or Vice President, they were directed to press a lengthy list of demands.

The delegates called for the restoration of the two-thirds rule, requiring that the Presidential and Vice Presidential nominees receive the support of at least two thirds of convention delegates. They also demanded that the party adopt a platform supporting segregated primaries (in defiance of Smith v. Allwright), protecting the poll tax, opposing required integration of schools, and upholding white supremacy. In addition, they demanded the replacement of Wallace on the ticket with House Speaker Sam Rayburn or someone similarly sympatico to Southern interests.

The anti-New Dealers also chose a slate of electors that were not only not bound to support the national Democratic Party ticket; they were instructed that if the convention did not meet their demands, they should vote for somebody else. That “somebody else” remained unstated: perhaps the Republican nominee, or perhaps a Southerner who was not a candidate.

The pro-New Dealers walked out and held their own rump convention, where they selected a different slate of delegates and electors, all pledged to support the party’s nominee.

Texas’s Democratic National Committeeman, Myron Blalock, tried to broker a truce between the two sides, but found them both unwilling to budge.

The Texas rebels would soon have company.

Magnolia and Palmetto States Join the Fight

In early June, the Mississippi Democratic Party voted to send an “uninstructed” delegation to the national convention, and to release their electors from the requirement to vote for the Democratic nominee in the Electoral College.

South Carolina opted for a wait-and-see approach. They sent a similar group of unpledged delegates to Chicago. As for the electors, they declared that they’d wait until after to convention to determine whether their electors would be bound to vote for the party’s ticket or if they would be similarly unpledged.

The three states combined could not deny Roosevelt the nomination. But if the election was close – which seemed possible – they might have enough votes to deny Roosevelt victory in the Electoral College, or at least force him to bargain for their votes.

The possibility was met with delight in many Southern papers.

“There’s revolt already against the Democratic Party,” exulted John Temple Graves in the Columbia Record. “[T]he South is capable of deserting the Democratic Party. For the first time since the War Between the States it is possible.”

“The South has been given the political brush-off throughout the New Deal,” wrote the Staunton Daily News Leader in an editorial (blithely ignoring the TVA). “[T]he Democratic tower of strength for generations, it is a step-child in its own home. Its growing revolt is a healthy indication of political independence which is its only hope.”

The Roosevelt administration, of course, wasn’t going to take this revolt lying down. Neither were its supporters.

Florida Sen. Claude Pepper lamented “the folly and tragedy of secession from the Democratic Party… threatened by reported plans to bolt in the electoral college.”

“If the Democratic Party splits,” he noted, “it means the certain election of a Republican, as it did in 1860.”

Columnist Drew Pearson pointed out that the South’s gambit might backfire. “What most people don’t realize… is that, in the Electoral College, the South is able to vote its Negro population even though the Negroes themselves don’t vote,” Pearson wrote.

States are assigned electoral votes by total population. But because many Southern states prevented blacks (and some poor whites) from voting, their turnout was much lower than in Northern states with similar populations.

“This added political strength which the South has enjoyed since the Civil War would evaporate if the Electoral College were abolished,” Pearson concluded. “And politicos of both parties agree that its abolition is just as sure as tomorrow if electors refuse to obey the mandate of the people.”

Showdown in Chicago

As the Democratic convention approached, a key question arose: Who would represent Texas? Both the anti-New Deal and pro-New Deal forces claimed that theirs was the legitimate Texas delegation.

The pro-New Dealers claimed the national party promised that they would be seated at the convention. “The [anti-New Deal] delegation might be welcomed in Chicago if they will repudiate… their work in Austin and assist in undoing it,” said Woodville Rogers, one of the leaders of the pro-New Deal delegation. “Otherwise, they are not entitled to sit in a Democratic convention.”

The anti-New Dealers fired back, “We have not so far had any reason to believe we will not be seated as the official delegates from Texas.” They had the somewhat reluctant support of Myron Blalock, who said he would recommend that the “regular” delegation be seated.

“There is, of course, talk of a possibility that both ourselves and the bolting delegates will be seated,” the anti-New Dealers’ statement continued, “but that is too absurd to contemplate.”

Turns out it wasn’t too absurd, because that’s exactly what happened: the convention split the Texas delegation between the “regular” and pro-New Deal groups.

This time, the anti-New Dealers walked out. They issued a blistering statement charging that “the bureaucrats, the CIO Political Action Committee, and a liberal sprinkling of Communists joined forces to tell Texas Democrats just where they stand in national politics.”

As for their demands, the convention largely told the rebels to pound sand. Roosevelt rolled to renomination on the first ballot, despite a handful of protest votes for Virginia Sen. Harry Byrd. The convention did boot Henry Wallace from the ticket, but instead of selecting a Southerner (like Jimmy Byrnes of South Carolina, reportedly FDR’s top choice), they opted for Harry Truman, a border-state moderate.

As for the platform, it contained no endorsement of white supremacy, the poll tax, segregated primaries, or segregated schools. Instead, it included a fairly anodyne statement arguing that racial minorities were entitled to equal protection under the law.

The Texas anti-New Dealers blasted the platform, which they claimed was “designed to secure the support of Negroes, the CIO, the Communists and other radical minority groups.” They vowed to “meet the challenge of these un-democratic elements, and… make sure that they shall not gain control of the Democratic Party.”

But how far would they go? America would soon find out.

The Struggle Continues… Then Collapses

After the convention, South Carolina continued to straddle the fence. The state Democratic Party met in early August and instructed its electors to vote for the Roosevelt-Truman ticket in the electoral college. But shortly thereafter, a group of so-called “Southern Democrats” got an unpledged slate of electors added to the ballot as well.

The Charleston News and Courier praised the unpledged-elector move. “In South Carolina eight Democratic candidates for presidential electors opposed to Messrs. Dewey and Roosevelt will be placed in the field,” they wrote. “We believe the majority of South Carolinians will vote for them.”

“As both national parties and their candidates are in policy hostile to South Carolina… it [would be] common sense for [the electors] to use their power under the constitution to gain now what advantage they can,” the editorial continued. “In a close contest… [g]uaranties of the South’s safety could be extorted from” one of the parties.

In early September, though, the plot began to unravel, as E.B. Germany – leader of the dissident Texans – overplayed his hand.

Germany wrote a letter to the electors of Louisiana and Mississippi, inviting them to join “a common program” with Texas to withhold their electoral votes until FDR made a deal with them.

“[T]hose in control of the Democratic party would be willing to bargain with the South rather than allow the Republicans to gain control of the patronage,” Germany wrote.

Unfortunately for him, one of the Mississippi electors, Rich Russell, was a staunch supporter of FDR and took extreme offense at Germany’s proposal. He shared the letter with the papers, saying that it confirmed “that there is some kind of selfish, iniquitous and hidden scheme behind all this Southern revolt against the Democratic party.”

Germany’s letter sparked an uproar. Louisiana quickly announced that it would not participate in the scheme. State Democratic Chairmen John Fred Odom announced that his state’s electors were bound to support the Roosevelt-Truman ticket, and if they felt otherwise, they “should resign and let some be elected who will carry out the mandate of the party.”

Germany’s stunt also pissed off Myron Blalock, who fumed that “It’s a fine come-off when we Texas Democrats have to find out from Mississippi what are the secret plans of Texas Democratic electors.”

He didn’t need this crap.

He promptly held another state convention. This time the pro-New Dealer were in the majority, and they replaced the “uninstructed” electors with a slate pledged to support the party ticket. (The dissident faction, who dubbed themselves the “Texas Regulars,” responded by filing the original electors as a separate slate on the ballot.)

But what about Mississippi? Russell aside, the electors remained noncommittal on their plans. Under pressure, they met in early September and pledged to vote for the Roosevelt-Truman ticket “unless something occurs which would make it contrary or inimical to the best interests of the people of Mississippi for us to do so.”

Apparently, something must have occurred, because at the end of October, three of the electors declared that they would vote for Harry Byrd in the Electoral College.

The New Orleans Daily States blasted this move as “a defiance of the will of the people. In plain language, the voters are told that they are a bunch of saps and don’t know what they want… Talk about bossdom, the attitude of the ‘rebel’ electors in Mississippi makes some of the dictators look puny and insignificant!”

In response to the electors’ mutiny, Governor Thomas Bailey called a special session of the legislature, which removed the rebels (along with two others who refused to pledge their votes for FDR) and replaced them with electors who agreed to support the administration. It was too late to remove the original elector slate, however, so they both appeared on the ballot.

All the states that had threatened revolt now had electors committed to vote for the administration. But they also had slates of unpledged electors. Now it was up to the voters.

A Failed Revolution… Or Was It?

On one level, the Electoral College revolt of 1944 was a total failure. None of the “unpledged” elector slates was chosen, and it wasn’t close.

In Texas, the “Regulars” got 11.8% of the vote, while the official Democratic slate received 71.4%. In South Carolina, the “Southern Democratic” slate received 7.5%, compared to 87.6% for the actual Democratic slate. In Mississippi, the original electors (including the rebels) got just 5.5%, while the pro-FDR slate received 88%.

Ultimately, Roosevelt was still hugely popular in the South, and the anti-New Deal dissidents a small minority. But even though this particular effort went nowhere, it still highlighted a few important things.

First, it demonstrated – as Kefauver and other reformers pointed out – the dangers lurking in the Electoral College system. All the papers that endorsed the Southern scheme took pains to stress that it was totally legal under the Constitution, which was true. But it shouldn’t be.

The electors are supposed to cast their ballots for the candidate who wins their state’s vote, but nothing requires them to do so. That opens the door for a plot like this.

It’s also worth noting that these rebel electors didn’t have an actual candidate. Many of them expressed plans to vote for Harry Byrd, but he never actually put himself forward as a candidate, and he explicitly stated that he did not encourage anyone to vote for him.

But it didn’t matter, because there was never any plan to elect Byrd President. They just needed a name, so that they could either trade their electoral votes for concessions from one of the actual candidates or force the election into the House.

Second, this revolt was strictly about civil rights and the South’s political power. Some of the pro-revolt editorials groused about the South’s supposed economic subjugation by industrialists from the North and East, or made noises about Communism and the all-powerful federal state. But if you look at the actual list of demands, there’s nothing about economic assistance for the South, lower taxes, or reduced bureaucracy.

All the demands – save for the restoration of the two-thirds rule, designed to give the South a veto over any candidate who didn’t meet their approval – were about civil rights. They wanted the Democratic platform to endorse segregation and white supremacy. Anyone who argued that this revolt was really about “states’ rights” or the size of government was selling a line of nonsense.

Finally, this set the stage for the Dixiecrat third-party effort in 1948. A lot of the folks involved in the 1944 revolt also showed up in the Dixiecrat movement four years later.

It’s also worth noting that the votes for anti-FDR electors were concentrated among the wealthiest parts of their respective states. Anyone who tries to claim this was a “grassroots” revolt is deeply misguided.

You might also wonder why the dissident Democrats never considered, you know, voting Republican. If you decide that the party you’ve long supported has abandoned you, why not vote for the other party? (Kefauver made this point in an essay six years later.)

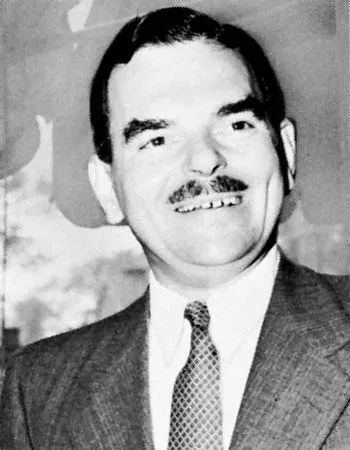

Well, old habits die hard; to a lot of Southerners, the Republicans were still the party of Lincoln, and they couldn’t stomach the idea of voting that way. Besides, it’s not like Republican nominee Thomas Dewey was any friendlier on civil rights issues.

It took another couple election cycles for Eisenhower to make real inroads into the Solid South, and a generation before Republicans really started flipping the region into their column.

At any rate, diving down this rabbit hole was a real eye-opener. I’m glad Kefauver opened my eyes to this chapter of history – and I’m left to wonder why my history classes didn’t.

Leave a comment