Estes Kefauver was forever thinking about ways our political system could work better. He proposed countless changes to the structure of the federal government, and numerous amendments to the Constitution itself. He waged a decades-long war to get rid of the Electoral College.

As a Presidential candidate, he was a trailblazer, the first candidate to attempt to win the nomination via the primaries, rather than the smoke-filled rooms at the convention. Kefauver had the unusual idea that the people, rather than party leaders, should choose their Presidential candidates.

Given Kefauver’s reformist tendencies and populist leanings, it’s no surprise that he also had ideas for reshaping national political conventions. He wrote up his proposals for reform in a New York Times Magazine article in March 1952.

He began by acknowledging what conventions did well. “As spectacles the national conventions have color and drama of wide public interest,” he wrote. “They tend to stimulate political activity on all levels, both national and local, which is desirable.”

But when it came to their stated purpose – to select Presidential candidates and determine the party’s platform – he felt that they left something to be desired, questioning whether “this is quite the way the two parties should conduct their business when such decisive choices and issues are at stake.”

What was wrong with the conventions in Kefauver’s eyes? For one thing, they gave too much power to party leaders and not enough to regular voters. “The method of selecting and instructing delegates in most states works to block adequate expression of rank-and-file opinion in most states,” he wrote.

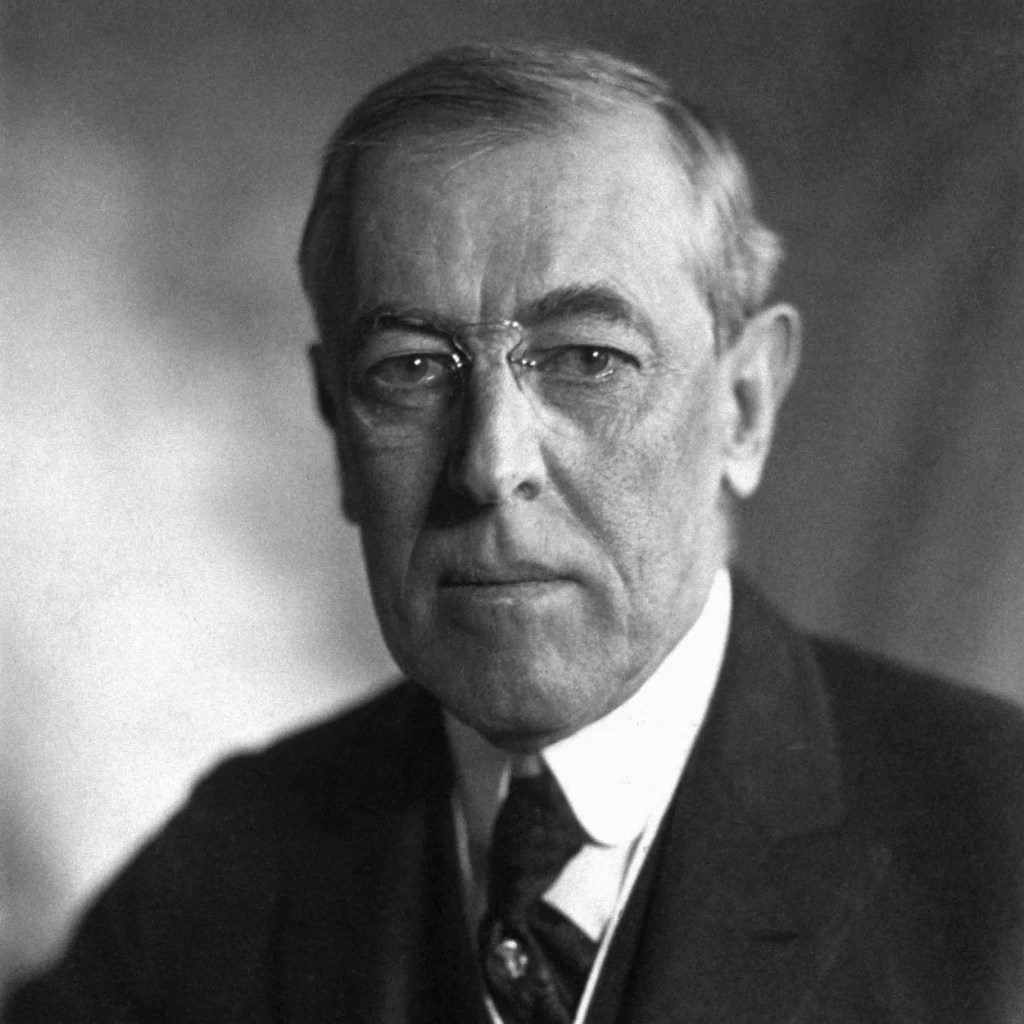

To fix this, he argued that the Presidential nominees should be chosen by primaries in each state. Critics likely scoffed that this suggestion was self-serving, given that Kefauver was widely unpopular with party leaders, but he pointed out that his was not a new idea: Woodrow Wilson had proposed it as early as 1913.

At the time of Kefauver’s article, only 16 states held Presidential primaries. And not all of those awarded delegates to the winner; some states essentially held glorified straw polls, for some reason. (Kefauver argued that delegates should be bound to the winner of their state’s primary until released by the candidate.)

“I regard it as the democratic right of the American people to have as wide a choice as possible in choosing their national leaders,” Kefauver wrote. “There is a place, and a need, for new blood and new ideas in both parties – a statement, I think, with which few will disagree.”

Party leaders ignored Kefauver’s idea at the time, but events would ultimately force their hand. After Hubert Humphrey won the Democratic nomination in 1968 without entering a single primary, the grass roots finally revolted. This led to the reforms of the McGovern-Fraser commission, finally dragging the party in the direction Kefauver had suggested twenty years earlier.

Kefauver understood that knowing the nominee in advance would make the conventions less interesting. “[L]eft with the task of writing platforms and directing party affairs [and] stripped of their role in nominating candidates,” he wrote, conventions “would [lose] their vitality.” (Time has proved him right; today, conventions are basically week-long infomercials for the nominee and the party.)

Given that, it might seem surprising that Kefauver wanted to hold conventions every other year instead of every four years. Why? With the conventions no longer focused on picking nominees, they could spend more time on what Kefauver considered underappreciated tasks: building up the parties and adopting national platforms.

During the existing quadrennial conventions, he pointed out, “[t]here is simply no time to deal adequately with such vital matters as strengthening party machinery, developing intraparty democracy and protecting local party organizations against the inroads of gamblers, gangsters, and other corrupt elements.” By meeting more frequently, these activities could receive the attention they deserved.

(The bit about gamblers and gangsters was an obvious callback to his hearings on organized crime, which had concluded the year before.)

Of course, “strengthening party machinery” doesn’t make for compelling television. That’s where the platform comes in.

Today, Presidential candidates generally treat platforms as an afterthought. But Kefauver envisioned them as the party’s chance to tell the voters what they wanted to accomplish. Essentially, it allowed them to set up their fall campaign.

Kefauver saw multiple benefits to this approach. For one, it would “dramatize the national importance” of midterm elections. For another, it would give the parties’ rising stars and potential future Presidential candidates a chance to introduce themselves to a national audience. Further still, it would allow the parties to react to events that occurred between Presidential election cycles.

To illustrate, he imagined if the parties had held conventions in 1950. The arrival of the Korean War, he suggested, would have dominated their thinking.

The war might have forced Republicans to resolve the conflict between the isolationist and internationalist wings of the party. Perhaps then Eisenhower wouldn’t have had to deal with the Bricker Amendment. (Or, if the party had committed to isolationism, Ike might not have run at all.)

On the Democratic side, a 1950 convention might have forced a reckoning with the Dixiecrat revolt of 1948 and helped the party come to an agreement on civil rights. “Probably the shock of Korea would have helped the Democratic party to pull itself together on a problem it must face,” Kefauver wrote.

Naturally, Kefauver wanted the people to have a voice on the platforms too. DNC Chairman Frank McKinney had recently established an Executive Committee consisting of representatives from each region of the country as well as three at-large members. The Executive Committee’s function was to share the “thinking of the people of America from coast to coast – from the big city to the smallest hamlet.”

Kefauver supported this move, but wanted to go even further. He wanted the Resolution Committee (assembled at each convention) to become a standing committee charged with keeping “their finger on the pulse of the party throughout the country.” They would maintain a dialogue with voters and local party and elected officials around the country in order to “keep in close touch with their problems and what they have on their minds.”

Having proposed dramatic changes in the structure and purpose of conventions, Kefauver also took aim at the selection of delegates. At the time, both parties had approximately 1,200 delegate votes. “For a country as huge and varied as the United States, 1,200 delegates are not too many,” he wrote. “They bring grass-roots sentiment into the convention and carry back to the folks at home the message of their party.”

However, many states split their delegations so that delegates might have only a half-vote or quarter-vote apiece. In addition, every delegate was assigned an alternate, each of whom was invited to attend. This meant that in 1952, each convention would have over 3,000 delegates, and that was too many in Kefauver’s eyes, rendering the conventions “an unwieldy and ineffective instrument.” He recommended abolishing or limiting the practice of splitting votes between multiple delegates, and significantly reducing the number of alternates in attendance.

In addition, Kefauver wanted to change how the delegates were apportioned. At the time, each state was assigned delegates by population, similar to the allocation of electoral votes. However, this created a variation on the UK’s “rotten borough” problem, where there were too many delegates from states dominated by the other party. So, Democrats in the Great Plains and (at the time) Republicans in the South were overrepresented at their respective conventions.

Kefauver recommended indexing the apportionment of delegates by both population and party strength in each state. The Democrats started moving in this direction in the 1960s, and today they use a formula that takes into account both electoral votes and the relative strength of the party into account. (As a result, there are many more delegates from Massachusetts than from Tennessee at the Democratic convention, even though both states have 11 electoral votes.)

As we can see, in the end some of Kefauver’s ideas were adopted, while others were not. As usual, he gets no credit for this, since the ideas were generally adopted after he died.

Among his ideas that weren’t adopted, I think the concept of holding conventions in midterm years has a certain appeal. It might have forced the parties to rethink the purpose of conventions, rather than watching them descend into near-irrelevance as the primary system became the primary avenue for choosing Presidential nominees.

One of the most successful midterm elections in recent memory was 1994, when Republicans used their “Contract with America” to capture houses of Congress, gaining 54 seats in the House and 8 in the Senate.

Perhaps midterm conventions would encourage both parties to develop coordinated campaign strategies like that. They wouldn’t all be as successful as the Contract with America, but they might help boost turnout and, as Kefauver said, dramatize the national importance of those elections.

At the time Kefauver wrote his piece, it might have come off as another poke in the eye of the political bosses he opposed throughout his campaign. But in truth, his suggestions feel like a sincere extension of his lifelong desire to reform the political system and give more power to the people. As he wrote in his piece, “There is nothing the matter with the two-party system and the institution of national conventions that more democracy cannot cure.”

Leave a comment