One of the sad ironies of Estes Kefauver’s career is that he was frequently – and falsely – accused of taking positions in service of his own ambition. Whether it was his vigorous and impartial management of the organized crime hearings or his refusal to sign the Southern Manifesto and his openness to civil rights, the party bosses and other Kefauver detractors wrote it all off as an act to curry favor for his Presidential bids.

In fact, almost every position and action that Kefauver took as a politician was grounded in genuine principle, whether it helped him or hurt him politically. The ironic part is that his career is full of examples where his stands on principle wound up hurting his chances to climb the political ladder.

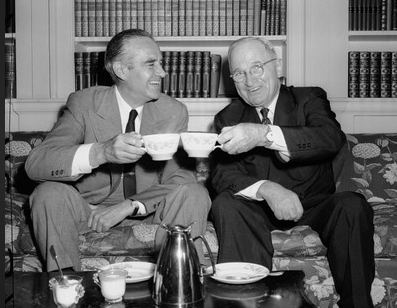

The crime hearings were arguably just such an example; they made him a national hero, but his refusal to soft-pedal or avoid revelations of crime and corruption in Democratic cities angered President Truman – a proud product of the Kansas City political machine – and other party bigwigs, who became determined to stop him at all costs from winning the Presidential nomination in 1952.

At the ‘52 convention itself, his unwillingness even to entertain a bill allowing states to engage in offshore oil drilling cost him the support of the Texas delegation, which might have allowed him to snatch the nomination anyway.

But if there were two things that did the most damage to Kefauver’s prospects for political advancement, they were his unwillingness to play by the rules of the Senate “club,” and his refusal to build a political organization. I talked a little about that first one in my article about Kefauver and LBJ. Today, I want to focus on the second one.

Given Kefauver’s general popularity in Tennessee and his impressive record in winning statewide elections, you might assume that he had a powerful home-state political organization working behind him. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Naturally, he had a group of supporters who turned out loyally to campaign with him whenever he was on the ballot. But he never – at either the state or national level – built the kind of network that reinforced his power and influence, or helped like-minded candidates get elected.

What’s more, that was a deliberate choice on Kefauver’s part.

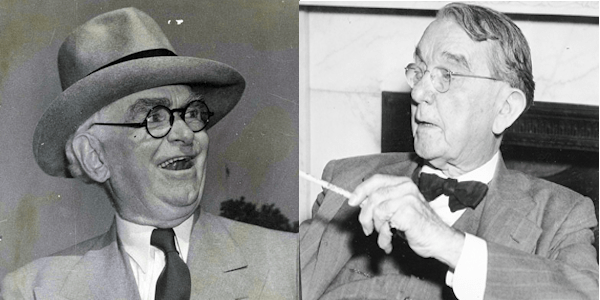

He certainly was quite familiar with how political machines worked. In 1948, he made it to the Senate by defeating the powerful Crump-McKellar machine in Tennessee. That was a classic political machine, combining Boss Crump’s control of votes in and around Memphis with Senator McKellar’s ability to dole out political patronage.

Shortly after Kefauver was elected to the Senate, a couple of his close advisors tried to convince him to start setting up a statewide political organization of his own, complete with operators in each county to coordinate requests for political appointments and dispense favors. Kefauver shut down any such talk immediately. “No, that’s the way other people operate in politics,” he told his advisors. “We’re not going to operate that way.”

As a populist, Kefauver was horrified by even the slightest appearance of machine politics, and he was determined to avoid ever becoming a political boss. This was a noble stance on his part, but it caused him numerous practical problems both in his own Senate bids and in his runs for President.

As biographer Charles Fontenay pointed out, Kefauver’s unwillingness to create a home-state political organization meant that “every race he ran in Tennessee had to be organized from scratch[.]” This made his re-election campaigns considerably harder than they had to be. His Presidential campaigns were even more ramshackle, chronically underfunded and understaffed.

His lack of organization definitely cost him at the 1956 Democratic convention. His home-state delegation was controlled by Governor Frank Clement, an ambitious man in his own right who had little interest in helping Kefauver.

This meant that when Adlai Stevenson threw the selection of a running mate to the delegates, Kefauver had to deal with a less-than-friendly home delegation as well as the ambitions of fellow Senator Albert Gore, who decided to throw his hat in the ring for VP as well. A friendlier delegation would surely have been able to keep Gore out of the running and consolidate support for Kefauver. (Ultimately, influential Nashville newspaper publisher Silliman Evans had to threaten to ruin Gore’s career in order to get him to drop out.)

The organization problem might also have cost Kefauver a third try at the Presidency in 1960. The Tennessee governor’s chair came open in 1958 (Clement was prohibited from running for consecutive terms). It wound up being a close three-way race between Agriculture Commissioner Buford Ellington, a Clement ally; judge Andrew “Tip” Taylor, who would run against Kefauver for Senate in 1960; and Memphis Mayor Edmund Orgill, a longtime Kefauver friend and supporter.

Kefauver obviously wanted his friend Orgill to win. But he was so concerned about being viewed as a boss that he was reluctant even to give Orgill his public endorsement. As a result, Orgill wound up finishing third, but just 9,000 votes behind the winner Ellington out of over 685,000 votes cast.

If Kefauver had been willing to campaign openly for Orgill – or if he’d built an organization to do it for him – the Memphis mayor likely would have won. And with a friend statewide political organization behind him, Kefauver might have been able to run for President and for re-election to the Senate simultaneously, as LBJ did that same year.

The other problem with Kefauver’s lack of an organization is that it meant that every campaign – whether for Senate or for President – became a personal endurance test for him. He held himself to a punishing campaign schedule, traveling all over, giving as many speeches and shaking as many hands as he could.

It was an exhausting way to run for office. And since Kefauver never took a race for granted, it meant that he subjected himself to this punishment five times – 1948, 1952, 1954, 1956, 1960 – in the span of a dozen years. Never mind the time he spent flying around the country to campaign for other Democrats. I’m convinced that the physical toll of his super-intensive campaigning contributed to his untimely death.

So whenever I read characterizations of Kefauver as a shallow, unprincipled publicity hound, it makes me mad. The man was deeply principled – to the point of harming his own career, even to the point of running himself into an early grave.

Leave a reply to Power of the Press: Drew Pearson’s Campaigns for Kefauver – Estes Kefauver for President Cancel reply