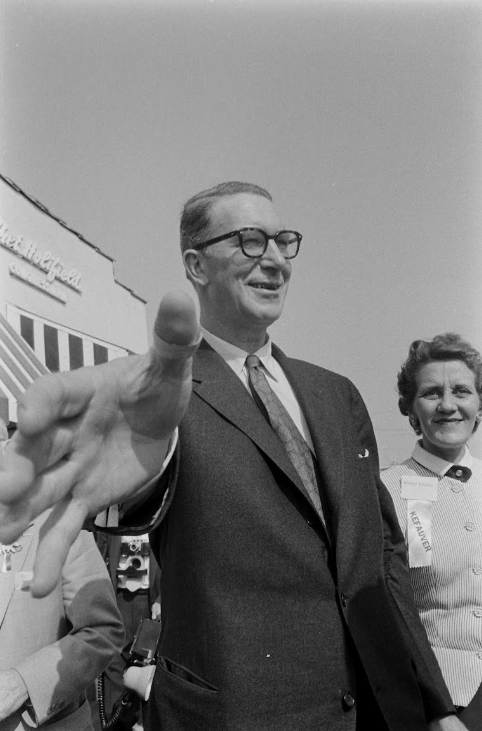

When Estes Kefauver ran for re-election to the Senate in 1954, one might assume that it would be a walk in the park. Kefauver had made an unusually big impression for a first-term Senator, with his televised hearings on organized crime earning national attention and leading him to launch a Presidential bid. And having effectively destroyed the Crump-McKellar political machine with his upset victory in 1948, he didn’t have to worry about them this time around. In theory, it should have been a breeze.

But as was the case throughout his career, nothing was easy. His Presidential run had actually created problems for him back home. And his reputation for independent-minded liberalism had upset the sizable conservative faction in Tennessee. As a result, Kefauver had to fight for renomination against a flamboyant Congressman with a checkered history, who mounted a curiously well-funded campaign.

Kefauver in ’54: Nationally Famous, But Locally Vulnerable

How did Kefauver’s Presidential campaign wind up damaging his status in Tennessee? First, needing to appeal to a nationwide audience led to him taking stances on some issues – particularly civil rights – that weren’t widely popular at home. But even more damaging was what happened at the Democratic convention.

Eager to avoid a replay of the Dixiecrat fiasco in 1948, Democratic leaders decided to make each state delegation take a loyalty oath, pledging to support the Democratic nominee in November. States whose delegations refused would not be seated at the convention.

Predictably, this plan went over poorly with many Southern states, who wanted to keep their options open, particularly since it wasn’t clear who the nominee would be at that point. The Virginia delegation, which was controlled by conservative Senator Harry Byrd’s political machine and which refused to take the oath, challenged their proposed exclusion from the convention.

Tennessee, whose delegation was controlled by Kefauver ally Governor Gordon Browning, voted against seating Virginia. (Ultimately, the convention seated the delegations from the Southern states – and several of them, including Virginia, wound up supporting Republican Dwight Eisenhower in the general.)

Browning’s actions angered a lot of voters in the Volunteer State, who blamed both the governor and Kefauver for betraying their “sister state” and the South generally. It contributed to Browning’s defeat by Frank Clement in the summer of 1952. Voter ire over the Virginia issue had cooled somewhat two years later, but conservative Democrats still disliked and distrusted Kefauver.

A coalition of conservative businessmen – unhappy with Kefauver’s stances on monopoly and antitrust issues – hoped to capitalize on the voters’ discontent by backing a high-profile primary challenger. They approached former Governor Prentice Cooper and former Senator Tom Stewart – whom Kefauver had unseated six years earlier – about launching a challenge, but both declined.

As it turned out, there was someone willing to run against Kefauver. But it wasn’t the sort of dignified elder statesman that the business community preferred; instead, it was an ambitious young blowhard who was convinced that he could talk his way into the Senate.

Enter The Challenger

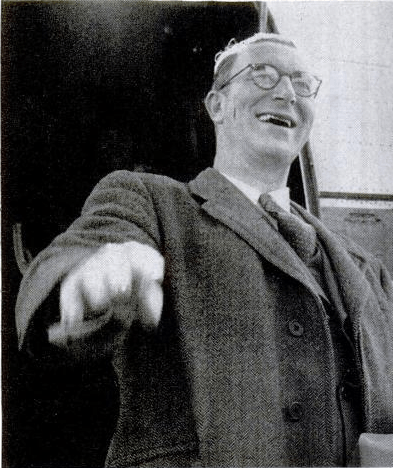

Pat Sutton was a 39-year-old Congressman in his third term representing a district south of Nashville. He was a genuine war hero; his service in the Pacific during World War II earned him a Distinguished Service Cross, a Silver Star, and a Purple Heart.

His most famous exploit occurred in the Philippines in February 1945. His squadron was marching toward Manila, when they came to a bridge that had been rigged with explosives by the occupying Japanese forces. The Japanese had lit the fuse on the bridge when Sutton ran through enemy fire to cut the burning fuse and save the bridge, allowing the Americans to march into Manila and retake the city.

It was an unquestionably brave act, and also reckless and a bit foolhardy. This combination of qualities basically summed up Sutton’s approach to life and, as it turned out, politics.

In 1948, he challenged incumbent Rep. Wirt Courtney, accusing him of absenteeism. (The charge was generally unfair – Courtney had missed many of the votes due to illness – but Sutton didn’t care.) Sutton also adopted a hyper-belligerent stance on foreign policy, calling on America to “tighten up on” the Russians, even to the point of war. “If it takes a war to stop them,” Sutton brayed, “we might as well have it.” He vowed that if America did go to war with the Russians, he would resign from Congress and “put on the uniform again.”

Sutton edged Courtney by just 58 votes, but the election was marked with accusations of fraud on both sides. In one county, state troopers were called to restore order after a group of Sutton supporters claimed that they were unfairly barred from watching the vote count at the courthouse and tried to force their way in. Sutton – despite being declared the winner – petitioned the Attorney General to order an FBI probe of the alleged vote fraud. (The Attorney General declined to take him up on this.)

While in Congress, Sutton continued his pattern of chasing headlines and making wild, unfounded accusations. In October 1952, Redbook magazine named him one of the worst Representatives in Congress, dubbing him a “wild swinger” and citing an incident in which he accused an Army general of using taxpayer dollars to build a hunting lodge at Fort A.P. Hill in Virginia which, Sutton claimed, Army brass were using as a party shack and bordello. It turned out that the charges were totally false; the hunting lodge was not built with taxpayer funds (it was already on the site when the Army bought), the accused general had never even used it, and it had never been used as a bordello (it was an officers’ quarters and mess until it was closed, months before Sutton made his accusations).

After six years of shenanigans like this, Sutton decided that he was ready for a promotion. And even though his voting record in Congress was similar to Kefauver’s, he ran hard to the incumbent’s right.

Sutton’s campaign rested heavily on two issues: Communism and civil rights. Taking a page from Boss Crump’s campaign against Kefauver in 1948, Sutton accused the Senator of being a Communist sympathizer. In an interview with the New York Times, Sutton charged that Kefauver “has consistently voted as a left winger, against the loyalty oath in the government, and against wire tapping to catch the Reds.”

During the primary campaign, Kefauver was the sole Senate vote against a blatantly unconstitutional bill to make membership in the Communist Party a federal crime. It was one of the most courageous acts of Kefauver’s career (although his campaign aides didn’t exactly appreciate it).

Sutton supplemented his Red Scare playbook with an appeal to segregationists. In May, the Supreme Court held in Brown v. Board of Education that “separate but equal” schools were unconstitutional. The idea of mandatory school integration upset a lot of people in Tennessee, and Kefauver ‘s call to abide by the Court’s ruling didn’t sit well with those people.

From the very beginning of campaign, Kefauver said, “I refuse to appeal to prejudice in connection with” the Brown decision, instead calling on leaders of both races to come together and discuss the best way forward. Sutton, meanwhile, was perfectly happy to appeal to prejudice if it would get him elected. In the words of journalist Ray Hill, Sutton was “doing his best to inflame racial discord” as he repeatedly attacked Kefauver on the civil rights issue.

While Sutton’s attacks may have been familiar, his campaign style was rather novel. He flew around the state in a helicopter, making campaign speeches with “the persistent zeal of a brush salesman,” in the words of Time magazine.

He supplemented these campaign stops with his “talkathons,” extended appearances on radio and television in which he appealed for campaign contributions while answering questions from voters for hours on end. One “talkathon” lasted for 27 hours. The talkathons successfully boosted name recognition for the previously obscure Congressman, and allowed Sutton to lob wild charges and distort Kefauver’s record without fear of immediate contradiction.

Sutton’s campaign whipped up a lot of sound and fury… but would it signify anything against the incumbent?

Kefauver Takes the High Road… Until His Patience Runs Out

Kefauver’s campaign staff advised him to ignore Sutton and focus on his own record in office. Initially, the Senator heeded that advice, proceeding with his usual campaign technique of traveling from town to town (in a car, not a helicopter), making speeches, shaking hands, and talking to as many voters as possible.

Kefauver made no attempt to dodge or parry Sutton’s attacks Sutton’s attacks on Communism and civil rights. Indeed, he didn’t mention his opponent at all. Instead, he patiently explained the reasons for his views to anyone who would listen, even those who disagreed with him.

In one small town, Kefauver paid a visit to a former supporter who opposed Kefauver’s views on civil rights and had switched to Sutton as a result. Kefauver asked the man about his views on the subject, then listened patiently while the man explained, not interjecting to rebut with his own opinion. After they had talked for over half an hour, Kefauver said, “I’m sorry. I know that you’re a big man, and I respect somebody with a different opinion,” shook the man’s hand and left.

Later, after the man had a chance to reflect on the conversation, a reporter asked him for his thoughts. The voter said, “I disagree. But he’s a deep man. He’s the only really deep man the South has in the Senate.” He wound up casting his vote for Kefauver.

Meanwhile, Sutton kept hammering away. Former Senator Kenneth McKellar – who had waged a blood feud against Kefauver during the four years they served together in the Senate – came out in favor of Sutton in early July.

The ambitious young Congressman tried aggressively to get Crump to endorse him as well, but the Memphis Boss – then in the last year of his life – stayed out of it. The few public comments he did make on the race were friendly to Kefauver; he praised the incumbent for his defense of the TVA and his handling of the organized crime probe. This didn’t stop Sutton from straight-up lying and claiming that Crump had endorsed him. (Crump quickly announced that he had not.)

Although it seemed like Sutton’s attacks weren’t landing with the voters, they were getting under Kefauver’s skin. At one point in midsummer, the mild-mannered Senator said to his campaign manager, “I’m getting awfully tired of Pat saying all those things about me.”

Having grown irritated with Sutton’s wild attacks, Kefauver began swinging back. In a campaign speech in Shelbyville, he warned voters against “little Hitlers and little Stalins” who were interested only in “personal power.”

As it turned out, that was just a warm-up for what was coming.

Follow the Money… to the Mob?

One thing about Sutton’s campaign had been a mystery from the start: Where was all the money coming from? His campaign was strangely well-funded for a man without great personal wealth or many prominent financial backers. Both the helicopter and the airtime for the talkathons cost a pretty penny. Who was paying for it all?

Sutton claimed that he had received a $150,000 contribution from Texas oilman H.L. Hunt. Beyond that, he was uncharacteristically vague.

Kefauver and his staff had an idea where Sutton might be getting his funding: the mob. Frank Costello and friends had been badly embarrassed by Kefauver’s televised hearings, and there were persistent rumors that they were silently funneling money to Sutton to exact revenge.

Once the Kefauver campaign began looking into the matter, they discovered a couple of suspicious connections. For one thing, one of the part-owners of Sutton’s helicopter was Costello’s accountant. For another, the talkathons had been coordinated by a man named Robert Venn, whose other clients included Mickey McBride and Al Polizzi, two men who had testified before Kefauver’s committee and who had ties to the Cleveland mob.

It was enough for the Kefauver campaign to raise public questions about the source of Sutton’s campaign funds. The pro-Kefauver Nashville Tennessean wrote a scathing editorial warning voters “to watch for the ‘outside’ money said to be coming in and to find out how the invaders would ‘place’ it to their best advantage.” The editorial asked whether Sutton was “willing to handle blood money for political gain – to sell out to the Chicago and New York mobs.”

As usual, when Sutton found himself in a hole, he broke out the steam shovel and kept digging. Though he denied receiving mob mob, he said that he “would rather have the backing of criminals than the support of ‘left-wingers’ who believe in overthrowing your government and mine,” because the gangsters would “only steal your money, not your country.” For some reason, this line of defense did not prove effective.

Sutton Keeps Talking… and Talking…

As Sutton saw his chances growing steadily worse, he became wilder and looser in his accusations. He claimed that “some of the people who are behind Estes Kefauver… I don’t consider Americans.” He falsely stated that Alger Hiss’s brother had donated to Kefauver’s campaign. In another case, Sutton claimed that a prominent Kefauver supporter was a Communist. (The supporter later successfully sued Sutton for defamation and won $25,000.)

Sutton also amped up his isolationist rhetoric, saying he was “for taking the United States out of the United Nations and the United Nations out of the United States.” He claimed that Kefauver’s support for international bodies like the UN, NATO, and Atlantic Union threatened American sovereignty and security. (Kefauver replied. “My opponent says that I am an internationalist. This he says in derision, but it is one of the few truthful statements he does make in his campaign.”)

Sutton also cranked up the appeals to racism. He railed against the concept of “Negro and white children attending school together, or of legislation forcing them to do so.” He accused Kefauver of telling an African-American newspaper in 1952 that if he were elected President, “there will be no segregation.” Kefauver had never said any such thing; Sutton made the quote up.

Kefauver responded that “it’s just deceit, pure deceit, on the part of my opponent to be talking like this. And it’s dangerous, for in doing so he seeks to recklessly stir up racial prejudice just for what he thinks will gain a few votes for himself.”

This was the heart of Kefauver’s message in the closing weeks of the campaign: Sutton was reckless and irresponsible, liable to say anything to further his own ambition. The challenger’s increasingly over-the-top statements, eerily reminiscent of the recently discredited Joseph McCarthy, only served to confirm Kefauver’s picture of him.

In the end, the primary wasn’t close. Kefauver won nearly 70% of the votes. He won in 91 of Tennessee’s 95 counties. Sutton couldn’t even win his own Congressional district.

In the end, the man who thought he could talk his way into the Senate wound up talking his way into a landslide defeat.

Postscript

As was typical for Tennessee in those days, the general election was a mere formality for Kefauver. There had been some talk of a serious challenger; Republicans had hoped that Ray Jenkins, who was general counsel in the Army-McCarthy hearings, would stand against Kefauver, but he declined. Instead, the Senator faced Nashville attorney Tom Wall, and cruised to victory by a 2-to-1 margin.

As for Sutton, he did not let his defeat snuff out his political ambitions. In 1956, he tried to regain the Congressional seat he’d given up to challenge Kefauver, but was crushed by Ross Bass, the man who’d succeeded him. In 1962, he ran for sheriff of Lawrence County, Tennessee – despite the fact that he and his brother were under federal investigation for their alleged involvement in a currency counterfeiting scheme.

Despite the legal cloud hanging over his head, Sutton managed to get elected sheriff anyway; however, he had to resign the following year after being indicted on the counterfeiting charges. He pleaded no contest and was sentenced to a year in prison.

Despite all of that, he made one last try for political office in 1976, making yet another run for his old Congressional seat. He lost the primary again to Bass, who lost in the general to incumbent Republican Robin Beard. After that, Sutton finally gave up on electoral politics, and retired to the antiques restoration business. He died in 2005 at age 89, and is interred at Arlington Cemetery.

Leave a reply to Mumbles and Mix-Ups: Kefauver’s Speaking Stumbles – Estes Kefauver for President Cancel reply