While reading Estes Kefauver’s article on electoral college reform (which I covered in detail last week), I shook my head that, 60 years later, we still haven’t fixed the myriad problems with our system of picking Presidents that Kefauver described then.

Toward the end of his article, Kefauver described an open, organized effort to steal the 1960 Presidential election. My reaction changed to shock. How had I never heard of this? How had we allowed this incident to largely disappear into history?

The story Kefauver told wasn’t about Richard Daley stuffing ballot boxes in Illinois or LBJ stealing Texas. Nor did it involve Richard Nixon engaging in dirty tricks to try and snatch an election he narrowly lost. (In fact, Nixon handled his loss gracefully, and declined to challenge the results.)

The attempted electoral theft would have installed as President someone who hadn’t been a candidate. If the plot had succeeded, it would have rendered the entire election meaningless.

And – as Kefauver pointed out – it would have been entirely legal. Nothing about the plot violated the Constitution. As Kefauver noted, it represented an effort “to control election results by exploiting the elector’s constitutional independence.” That effort remains possible to this day.

One might argue that because the plot ultimately failed, it’s okay that we’ve forgotten about it. But the fact that it could have succeeded – and arguably came too close for comfort -makes it worth remembering.

“In the emotionally-charged climate of presidential elections,” Kefauver wrote, “…enough electors might follow [the 1960] example to change the result of an election.” Today’s political climate is at least as emotionally charged as it was then. Since the holes in the system that Kefauver pointed out are still there, we should understand how those holes can be exploited – and how easy it might be to do so.

Southern Discomfort

The plot to steal the 1960 election sprung out of the ongoing political realignment of the South. As Kefauver noted in his article, the Democratic “Solid South” was becoming a lot less solid. The New Deal coalition was beginning to fall apart, and Southern conservatives in particular were starting to feel less loyal to the Democratic Party.

The cracks first became visible in 1948, when Strom Thurmond’s Dixiecrats won nearly 1.2 million votes, along with 39 electoral votes from five different states. The Dixiecrat defection didn’t stop Harry Truman from getting re-elected, but it was a sign of things to come.

In the next couple cycles, Southern conservatives began moving away from the Democrats. In 1952, Dwight Eisenhower won four states from the former Confederacy: Florida, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia. In 1956, Republicans captured Louisiana and the border states of Kentucky and West Virginia.

Some conservatives explored third-party options. In ’52, General Douglas MacArthur ran under the Constitution Party banner and received about 17,000 votes. In ’56, the States’ Rights movement floated two Virginia candidates: T. Coleman Andrews and Senator Harry Byrd. The two received over 115,000 votes combined. The’52 and ’56 efforts failed to win any electoral votes, but they indicated the rising level of discontent in the South.

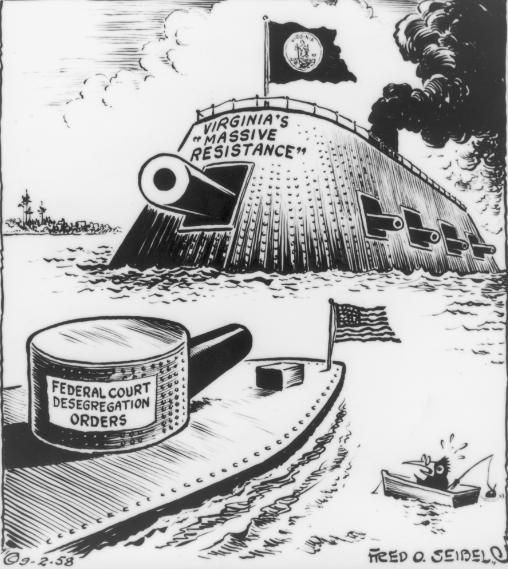

Some of that discontent, certainly, revolved around economic issues; some fiscal conservatives opposed the flood of government spending associated with the New Deal. However, the primary flashpoint was civil rights.

The Dixiecrat Party was born after the Democrats included a civil rights plank in their 1948 platform. The Supreme Court’s decision in Brown vs. Board of Education to mandate desegregation of public schools only further fueled the backlash, as did the passage of the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960.

Southerners no longer had enough clout within the Democratic Party to counter the growing sentiment among blacks – and Northern whites – in favor of civil rights legislation. But the Republicans weren’t any more hospitable to their cause (at least not at that time). Thus, a growing segment of the population in an electorally important region was getting restless, but they had nowhere to go.

Not Tonight, Dear, I’m Unpledged

That set the stage for the 1960 election. Neither ticket held much appeal for Southern conservatives. John F. Kennedy’s effort – with the assistance of his brother Bobby – to free Martin Luther King Jr. from an Atlanta jail during the campaign improved his standing among blacks, but only heightened skepticism among Southern whites. Richard Nixon would appeal to Southern discontent during his 1968 campaign, but in 1960 he was better known for his role in shepherding the Civil Rights Act of 1957 through Congress.

Given this, some Southerners were already looking for alternatives ahead of the election. As in ’52 and ’56, there were minor third-party efforts; Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus received 44,000 votes as a States’ Rights candidate, and Mississippi’s Charles Sullivan garnered another 18,000 as a Constitution Party candidate. But there was nothing on the scale of the Dixiecrat effort in ’48.

Instead, some Southern states put forth slates of “unpledged” electors, not bound to vote for any candidate. They’d hoped this would entice the parties to adopt positions more sympathetic to Southern interests. And maybe, if the election was close enough, those unpledged electors might prove decisive, and they could extract concessions from the candidates in exchange for their electoral votes.

Both Mississippi and Louisiana put both dueling slates of unpledged and pledged Democratic electors. Alabama settled for a weird hybrid; their single Democratic elector slate consisted of five electors pledged to Kennedy and six unpledged electors.

As it turned out, the election was close; Kennedy won the popular vote by just 112,000 votes, a 0.2% margin. But he captured over 300 electoral votes; some of the states he flipped back to the Democratic column included Texas, Louisiana (where the unpledged slate went down to defeat), and West Virginia. The unpledged Democratic slate won in Mississippi, as did the half-dozen unpledged electors in Alabama. But Kennedy had secured an electoral college majority, and those electors weren’t enough to swing things by themselves.

The unpledged gambit had failed, and the election was over. Or so it seemed. For a few people, on the other hand, it was just getting started.

Let The Games Begin!

The chief architect of the election-theft gambit was R. Lea Harris, an attorney from Montgomery, Alabama. Harris, a conservative Democrat and no great fan of Kennedy, came up with a plan: If he could get all of the Republican electors, the unpledged electors, and some portion of the Democratic electors to vote fore someone other than Nixon or Kennedy, he could overturn the result of the election.

In theory, such a plan could work. Nixon had earned at least 220 electoral votes. If Harris convinced all of those electors that a vote for Nixon was meaningless and persuaded them – along with the 14 unpledged electors from Mississippi and Alabama – to vote for another candidate, then he’d only need about 35 faithless Democratic electors to secure an electoral-college majority.

On November 9, Harris wrote to all electors – Republican, Democratic, and unpledged – to share what the Associated Press described as “a proposal to upset Sen. John F. Kennedy’s election or force him to revise certain programs.” The AP didn’t specify those “certain programs,” but subsequent events would make clear which ones he had in mind.

(One might imagine that he would only contact Republican and Southern Democratic electors, since they were the most likely to go along with his scheme. But he cast as wide a net as possible. A Pennsylvania elector named Guy Swope reported Harris’ letter to the AP. Swope was uninterested in the scheme: “The electors could probably vote for anyone they wanted,” he told the AP, “but they wouldn’t go back to their home districts afterward.”

Harris received few replies, but one Republican elector, Henry Irwin of Oklahoma, wrotethat he was on board. He also offered to recruit his fellow Republican electors to join in.

With Irwin’s concurrence, the plan was afoot. Just one thing: they needed a candidate.

Byrd’s the Word

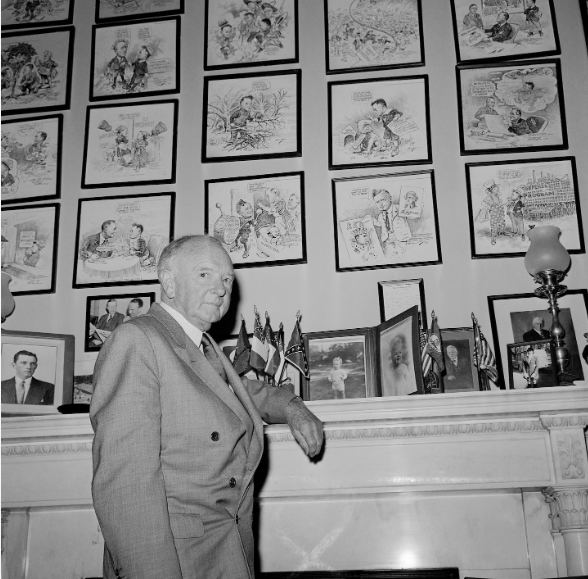

In retrospect, it was unsurprising that they chose Harry Byrd as their standard bearer. The Senator from Virginia had been a favorite of disaffected Southern Democrats for decades.

At the 1944 Democratic convention, anti-FDR forces nominated Byrd for President. In 1952, he received the Vice Presidential nomination from the Constitution and America First Parties; and as mentioned above, he was chosen by one States’ Rights faction as their candidate in 1956.

Although the Virginia Senator never actively sought any of those nominations, the affection was clearly mutual. Byrd was one of the first Southern conservatives to break with the national Democratic Party.

In 1952, Byrd refused to endorse Adlai Stevenson for President. While he did not formally endorse Eisenhower, his political machine worked to ensure a Republican victory in the state. The Old Dominion remained in the Republican camp in 1956 and 1960, again with the Byrd machine’s tacit support.

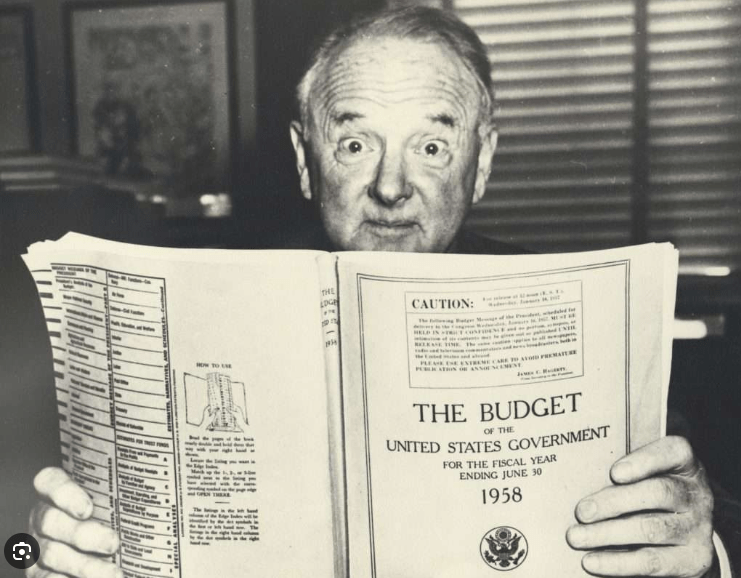

Why had Byrd fallen out with national Democrats? One important reason was that he was a staunch fiscal conservative. Byrd famously implemented a “pay as you go” strategy as Virginia’s governor in the 1920s. And though Byrd initially backed FDR when he first came to the Senate in 1933, he quickly became a critic of the President’s New Deal spending programs. Byrd soon became notorious for his opposition to virtually all forms of federal spending.

But that’s not the main reason why he was so famous among Southern Democrats in the 1950s.

Byrd was one of the leaders of the pro-segregation forces in the Senate. He proudly signed the pro-segregation Southern Manifesto. He was also the architect of “massive resistance,” a series of laws and court cases intended to prevent school integration.

It’s not clear whether it was Harris or Irwin who first chose Byrd. While the Senator was not formally involved with the plan, telling reporters he was “taking no part in the maneuver to withhold enough Electoral College votes to keep both Kennedy and Nixon out of the White House,” he didn’t disavow it either. One thing was clear: Byrd was a candidate that both conservative Democrats and Republicans could support.

The Plot Thickens

As it became clear that Harris’ strategy might have legs, several Southern states indicated that they’d support overturning the election. Georgia declared that its 12 electors were released from their pledges to support Kennedy, and Governor Ernest Vandiver – who had openly urged the electors to vote for someone other than Kennedy during the summer – refused to commit to supporting Kennedy, who had won the state handily.

The Georgia electors received letters and telegrams from around the country. One writer from Nebraska urged “in the interest of Constitutional government and liberty and freedom” that the electors withhold their votes from Kennedy ”in the hope that the election of our next President will be thrown into the House of Representatives and we thus have a chance to have a real patriot as our next President.”

In Louisiana, conservatives in the legislature called for Kennedy and the governors of the Southern states to meet in Baton Rouge. At the meeting, Kennedy would be told that in order to receive the electoral votes he had earned in those states, he needed to agree to three conditions: “(1) Eliminate the present sizable foreign aid we presently give to the Communist economy; (2) adhere to the spirit of the 10th Amendment; and (3), appoint one of these Southern Governors Attorney General.”

The 10th Amendment states that any powers not explicitly granted to the federal government in the Constitution were reserved for the states; the Southern states’-rights movement argued that this meant that the federal government had no authority to enforce civil rights laws. Appointing a Southern governor as Attorney General ensured that Kennedy could not back out of his pledge on the 10th Amendment.

The proposed Baton Rouge meeting never took place. Undaunted, the conservatives demanded that the state suspend its election laws so that a slate of unpledged electors – presumably the same slate that lost on Election Day – could be appointed instead.

Meanwhile, Irwin was hard at work on the Republican side, wiring every GOP elector with the following message:

I am Oklahoma Republican elector. The Republican electors cannot deny the election to Kennedy. Sufficient conservative Democratic electors available to deny labor Socialist nominee. Would you consider Byrd President, Goldwater Vice President, or wire any acceptable substitute. All replies strict confidence.

Irwin received about 40 replies. The majority indicated that the electors felt bound, either legally or morally or both, to vote for Nixon. However, 13 electors said that they were open to the Harris-Irwin scheme if it had a chance of succeeding; another three said that they would be interested if they could be released by their state party organizations from their pledges to back Nixon.

Based on these responses, Irwin concluded that the main obstacle to his plan was the “false assumption” that electors were obliged to vote for the candidate who had won their state. To deal with that, he sent telegrams to Republican national committeemen and state party chairs across the nation, urging them to support releasing electors from their pledges.

This time, Irwin got six responses, half of which expressed interest in the idea. One New Mexico committeeman said that he’d discussed the idea with party leaders “at the highest level,” and said that the leaders were in favor of the plan, as long as the party was not publicly sponsoring it.

As the December 19 electoral college meeting approached, Irwin and Harris bombarded the electors with letters, telegrams, and pamphlets urging them to be “free voters.” Although they hadn’t gotten the commitments that they sought, they held out hope of picking up enough defectors to at least force the election into the House of Representatives, and then.. who know what might happen?

The Steal is Stopped

In the end, the Harris-Irwin election plot fizzled. The unpledged electors in Alabama and Mississippi went for Byrd. But the Georgia and Louisiana electors all wound up voting for Kennedy. And the only Republican elector to vote for Byrd was Irwin himself. (Irwin couldn’t even agree with his co-conspirators on the ticket; he voted for Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater as vice president, while the others chose Strom Thurmond.) Kennedy wound up receiving 303 electoral votes, more than enough for an electoral college majority.

Irwin’s stunt infuriated the Oklahoma GOP. State party chairman Henry Bellmon said that Irwin “acted entirely on his own for reasons I don’t understand. He apparently feels his opinion is superior to the judgment of the one-half-million Oklahoma voters who chose Richard Nixon.”

To prevent future shenanigan, Oklahoma revised its election laws to force electors to sign a party loyalty oath and impose a $1,000 fine on faithless electors. Irwin was unapologetic, saying, “I was prompted to act as I did for fear for the future of our republic form of government.”

When Kefauver’s subcommittee held hearings on electoral college reform in 1961, Irwin testified, still unashamed of his actions. He admitted that, although he had been chosen as an elector to vote for the Republican ticket, he never intended to vote for Nixon. He also said that the changes in Oklahoma election law –both the pledge and the fine – wouldn’t deter him from trying again.

Indeed, he and Harris had already set their sights on 1964, when Irwin hoped to bring about “a return to respect for the Constitution by the election of a conservative coalition government.” The pair took out ads and sent out pamphlets urging “friends of the movement” to become electors in their states.

Epilogue: Lessons Unlearned

1960 was the high-water mark for the unpledged elector movement. Although Alabama put forth an unpledged slate in 1964, the state – along with four others in the South – wound up backing Barry Goldwater. After another major third-party movement for George Wallace in ’68, the South wound up swinging to the GOP, a realignment cemented at the Presidential level by Ronald Reagan in 1980 and at the Congressional level in 1994.

Even though the Harris-Irwin scheme failed and was never tried again, I believe it should be remembered as more than a historical curiosity, for two reasons.

First, none of what Harris and Irwin did was illegal or unconstitutional. That’s the reason why Irwin was comfortable testifying to the Senate about the scheme. And as Kefauver pointed out, it shouldn’t be possible for the electoral college to select a President who wasn’t even a candidate. The fact that this catastrophe hasn’t happened yet isn’t the point; it shouldn’t be possible.

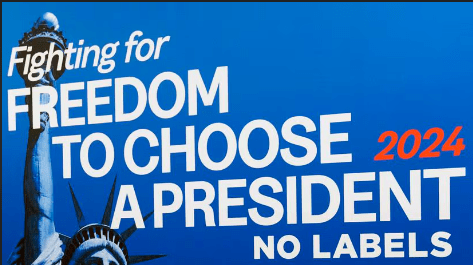

Second, our current times seem unusually ripe for someone to try something like this again. One of the major storylines of the 2024 election is the sense of widespread voter unhappiness with both major-party candidates.

The “No Labels” movement spent a lot of money and garnered a lot of headlines trying to recruit a moderate candidate who could capitalize on that discontent. What if No Labels, or a similar group, tried to convince the electors to abandon their commitments to Biden or Trump in favor of Joe Manchin, Larry Hogan, Chris Christie – or someone else?

Does it seem like such a farfetched idea? And given the level of political tension in the country right now, can you imagine the chaos that would ensue if it succeeded? Even if it didn’t, imagine the pressure that the electors would be under. It would make 1960 look like a day at the beach.

Kefauver foresaw the possibility of a 1960-style election theft scheme happening again, and tried to prevent it. We didn’t listen – and I hope we won’t have to pay the price for that in the near future.

Leave a comment