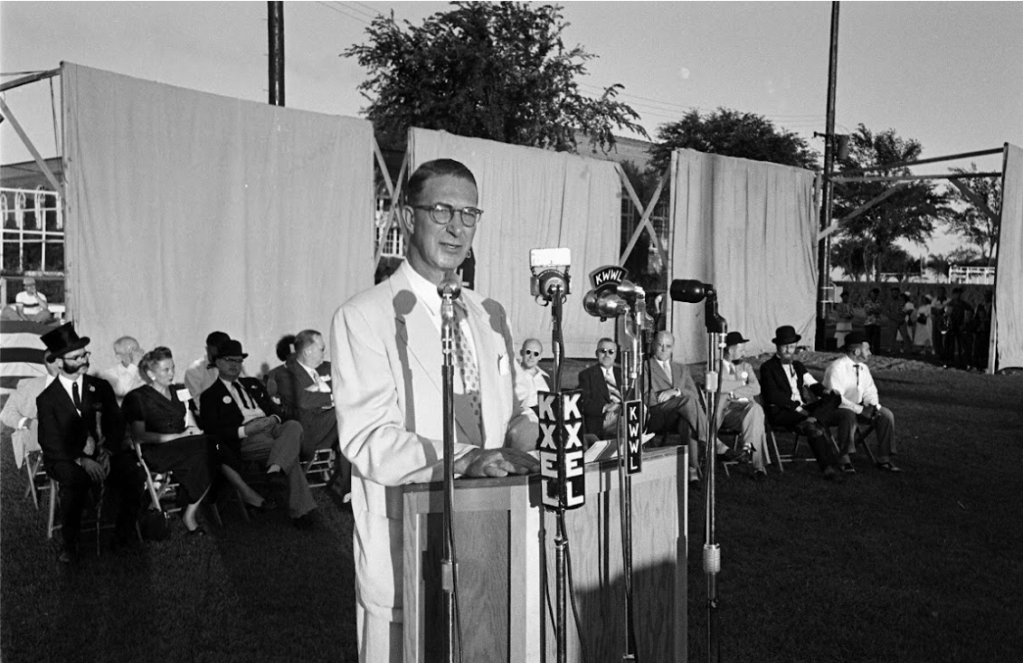

One of Estes Kefauver’s great political skills was launching attention-grabbing Senate investigations. His televised hearings as chairman of the Senate special committee on organized crime rocketed him to national fame and a Presidential run. Later in his career, his investigations of juvenile delinquency and monopoly and antitrust also garnered nationwide notice.

What if I told you that, in the year Kefauver first ran for the Senate, he wrote an article in a national magazine attacking “headline-hunting Congressional hearings” and calling for the abolition of special committees like the one that would later make him famous? Would you consider him a hypocrite?

Kefauver really did write that article. But as you might expect, the story is a little more complicated.

Calling Out Congressional Globetrotting

Kefauver’s article, entitled “Let’s Cut Out These Congressional High-Jinks,” appeared in the April 1948 issue of the American magazine. Running against the Crump machine in Tennessee, Kefauver wanted to show off his credentials as a populist reformer. With that in mind, the article sought to demonstrate that he was not a member of the Congressional insider’s club.

“I think it is high time,” he wrote, “that some member of the Capitol Hill family stood up and said to that ancient and honorable body, ‘Let’s cut out these Congressional vaudeville shows.’”

What were these “vaudeville shows” that Kefauver found objectionable? He focused on two: Congressional junkets and committee “investigations” that were useless or actively harmful.

Congressional junkets have long been controversial. Members claim the trips are necessary, allowing them to study complex issues in a way they couldn’t get from reading a report. Critics argue that too many Congressional trips amount to taxpayer-funded vacations (or, worse, attempts by foreign governments and multinational corporations to buy influence).

Kefauver made clear that not all foreign travel by Congress was wasteful. “It is highly useful,” he wrote, “for Congressmen… to take a hardheaded, firsthand look at what they are voting on.” For that reason, he felt that calls for a blanket ban on Congressional foreign travel “would be an act of blatant demagoguery.”

Instead, he objected to “any trip at government expense that serves no purpose.” Specifically, he called out two major issues: multiple committees making redundant trips to the same countries, and “useless travels to sunny and pleasant climes, which have already been investigated to death by committees that have gone before.”

Kefauver illustrated his first complaint by discussing “The Great European Emigration” of the previous summer. At the time, the Marshall Plan was investing considerable money to rebuild European countries devastated by World War II. It made sense that Congress would investigate to see how that money was being spent.

It made less sense, Kefauver pointed out, for four separate committees to travel to Europe at the same time to study the same issue. There was no attempt to coordinate between committees to share information or divide up the investigating. “Is it necessary for one committee after another to cover the same ground?” Kefauver asked.

Worse yet, he felt, was the endless parade of trips to “investigate” tropical places. The most popular destinations for such junkets, at the time, were Hawaii and Panama. Dozens of committees found excuses to travel to these paradises. Several of them never even bothered to file reports with the “findings” of their expeditions.

Kefauver mentioned that as a young Congressman, he’d gone on an “official” visit to Panama and had a fine time. “But what I learned,” he admitted, “could have been absorbed through a movie travelogue.”

According to Kefauver, “junketitis” had gotten so out of control that during the previous fall, nearly 200 members of Congress were away simultaneously on travel. He recalled running into a committee staffer that fall, who was laughing because another committee had asked her for help figuring out just how many Congressmen were out of town. “They thought they knew just which of their own members were on the road,” she said, “but they weren’t sure about anyone else!”

What did Kefauver propose to curb the outbreak of “junketitis”? He admitted the problem was tough to solve: “since Congress makes its own rules, the desire to take the cure must be present.”

That said, he had some ideas. For instance, House and Senate committees studying similar issues could coordinate and send a small joint delegation to travel and report back to the full committees. He also proposed giving the Rules Committees in both houses the authority to approve proposed trips; they would veto any trips that duplicated those either already underway or recently completed by other committees. Finally, he suggested a joint House-Senate committee specifically charged with coordinating travel and investigations, in order to limit duplicate inquiries.

What’s So Special About Special Committees?

Kefauver’s subsequent Senate career did not involve a ton of foreign travel, so his criticism there would not appear hypocritical in hindsight. His attack on special committees was another story.

Kefauver’s article criticized investigations that “serve little purpose except to waste the time of busy government officials and to get headlines for still another committee chairman.” He also argued that “it is not within the scope of Congress to strive for ‘exposures’ merely for political purposes.”

Kefauver’s critics certainly could have had some fun with these statements in later years. The most common attack on his hearings was that they garnered headlines but didn’t result in much legislation.

But on closer look, his concerns didn’t apply to the investigations he would hold during his Senate career. What bugged him, primarily, were redundant investigations and those that smeared the reputations of innocent people who couldn’t fight back.

As an example of the latter, he cited a Senate investigation into alleged speculation in the grain market by members of the Truman administration. The investigating committee published a list of everyone who had engaged in grain trading during that period, including hundreds of private citizens who had done nothing wrong.

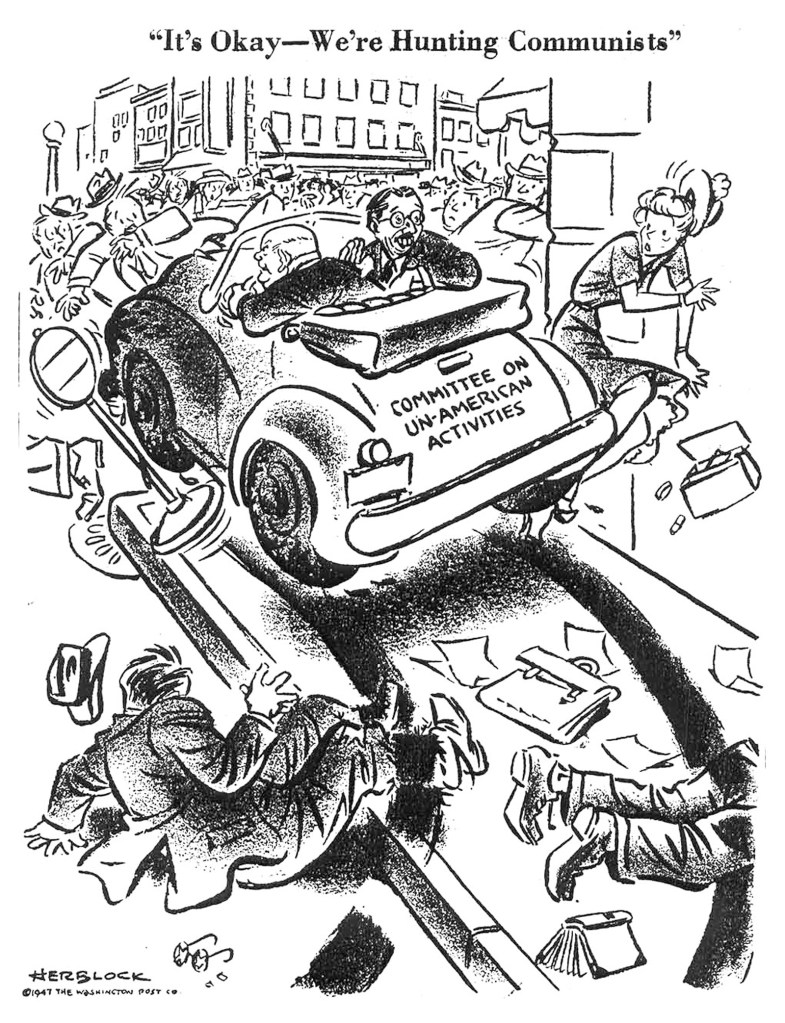

The committee that drew his greatest ire, however, was the House Un-American Activities Committee. This was no surprise; Kefauver – a lifelong defender of civil liberties and freedom of thought – was generally opposed to HUAC’s mission. He believed the committee was careless with accusations of disloyal conduct and ran roughshod over citizens’ Constitutional rights. In his article, he drily noted that HUAC “does little to maintain the prestige of Congress.”

The previous year, the committee conducted its infamous hearings into alleged Communist infiltration of the motion-picture business, which led to several directors and screenwriters being blacklisted due to their refusal to cooperate.

Rather than focus on the blacklisted figures, who were controversial, Kefauver looked at the Motion Picture Association of America, which represented film producers. The MPAA had promised to comply with HUAC’s investigation, but were not compliant enough for the committee’s liking.

Paul McNutt, the attorney representing the MPAA, requested the right to cross-examine witnesses; Chairman J. Parnell Thomas rudely shot McNutt down. Kefauver argued that the right of the accused to question his accuser was “a traditional American right,” and that HUAC was wrong to deny it.

During the same hearings, Walt Disney groundlessly claimed that the League of Women Voters was infiltrated by Communists. (It turned out he’d confused the LWV with a left-wing consumer group called the League of Women Shoppers.)

When the LWV asked for a chance to defend themselves in the hearings, HUAC ignored them. Only after the hearings did Disney submit a letter retracting his charge against the LWV; the committee quietly slipped the letter into the final hearing record without publicizing it.

While Kefauver agreed that rooting out Communist influence in American institutions was a worthy goal, he argued that it wasn’t worth curtailing Americans’ Constitutional rights.

He argued that the problem with special committees was that they “usually feel [they have] to justify [their] existence by doing something sensational, and [their] performance often degenerates into pure vaudeville.”

He felt that the solution was to abolish special committees altogether, arguing that regular committees could do the same work just as well. He also argued that witnesses should have the right to cross-examine their accusers, and that other rules should be enacted to curb committee misbehavior (a subject he’d return to again during the abuses of the McCarthy era).

A Little Hypocrisy, But A Lot of Truth

A cynic might note that Kefauver’s qualms about special committees didn’t prevent him from agreeing to lead the organized crime committee. And that investigation certainly included plenty of “sensational” moments, famously becoming a national drama. Critics of those hearings argued that the accused crime bosses and corrupt officials didn’t have much of an opportunity to defend themselves, either.

Given all that, it seems surprising that this article wasn’t thrown back in Kefauver’s face during his Senate career and his Presidential runs by Time magazine or his other detractors.

Of course, opposition research was tougher in those days. This article doesn’t seem to have garnered widespread national attention. And when Kefauver ran for President, it wasn’t like his opponents could go to Google and pull this up. They’d have to go through the stacks at the library, and that was unlikely unless someone knew what to look for.

There was certainly no shortage of material about Kefauver; who had time to go through it all? Better to focus on things he’d said recently that people still remembered.

To return to my question from the top: Do Kefauver’s charges look hypocritical in light of his later career? A little bit, sure. He certainly didn’t mind splashy, headline-gathering Congressional investigations when he was running them. And while he wasn’t one for foreign junkets, his critics pointed out his frequent absences from the Senate while he was off campaigning and making speeches.

But most of Kefauver’s critiques were on the mark. “Investigations” that amount to paid vacations are a waste of time and money, as are redundant investigations into the same topic. HUAC was frequently reckless in its accusations and conduct, and Congress should be able to conduct investigations without violating people’s Constitutional rights.

Kefauver was also right to call out another important check on Congressional misbehavior. Congress should have the integrity and courage to police itself, but so should voters.

“The voters can help by keeping a close eye on the performance of their Congressmen,” he wrote, “and by doing their best, through the power of the ballot, to keep the junketeers, the time-wasters, and the vaudeville actors out of Congress.”

That statement is as true today as it was when Kefauver wrote it almost 80 years ago.

Leave a comment