Opponents of Estes Kefauver’s Presidential campaigns often claimed he didn’t stand for anything. According to critics like Time magazine, Kefauver was an empty-headed demagogue who hid behind nice-sounding but meaningless slogans (like “an even break for the average man”), whose views shifted like a weathervane in a prairie storm, always pointing whichever way the popular wind was blowing.

To his critics, the only thing Kefauver really believed in was his own ambition, and he was willing to say whatever he thought would get him elected.

The critics were dead wrong. In fact, Kefauver held deeply-rooted principles, which frustrated his ambitions as much as they fueled them. His views were not empty or incoherent; Kefauver’s vision of how America should work was more consistent than most other politicians of his era, or even our own.

In this article, I’ll lay out Kefauver’s beliefs, and how they shaped his political worldview. If that worldview was lacking, it was not in meaning or structure. Rather, he may have expected too much of us and our institutions.

A Profound Faith in the People

To begin with, Kefauver was a populist – in the best sense of the word.

Today, we think of populists as those who manipulate popular sentiment, stoking anger against vaguely-defined “elites” supposedly trying to screw over the people.

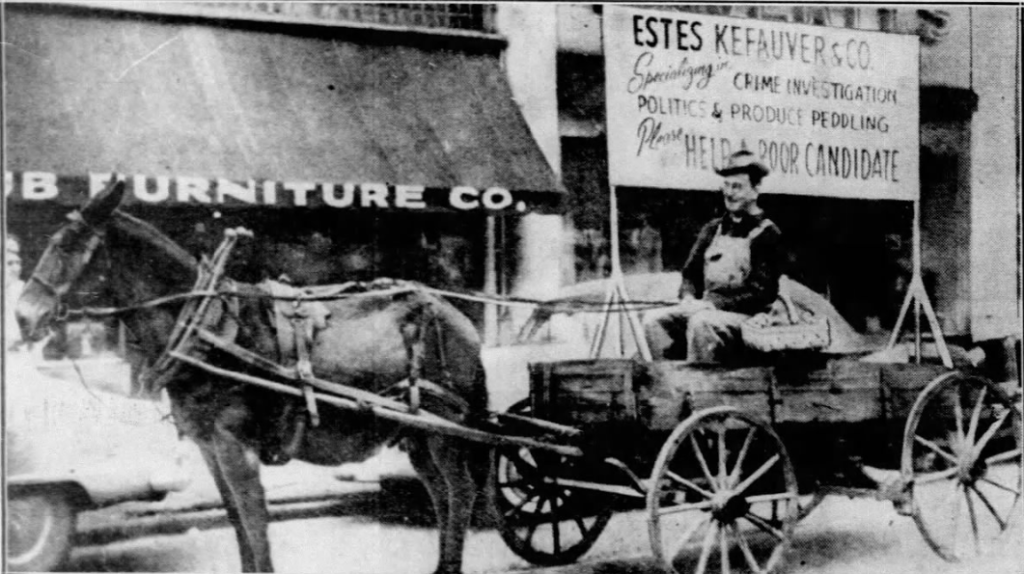

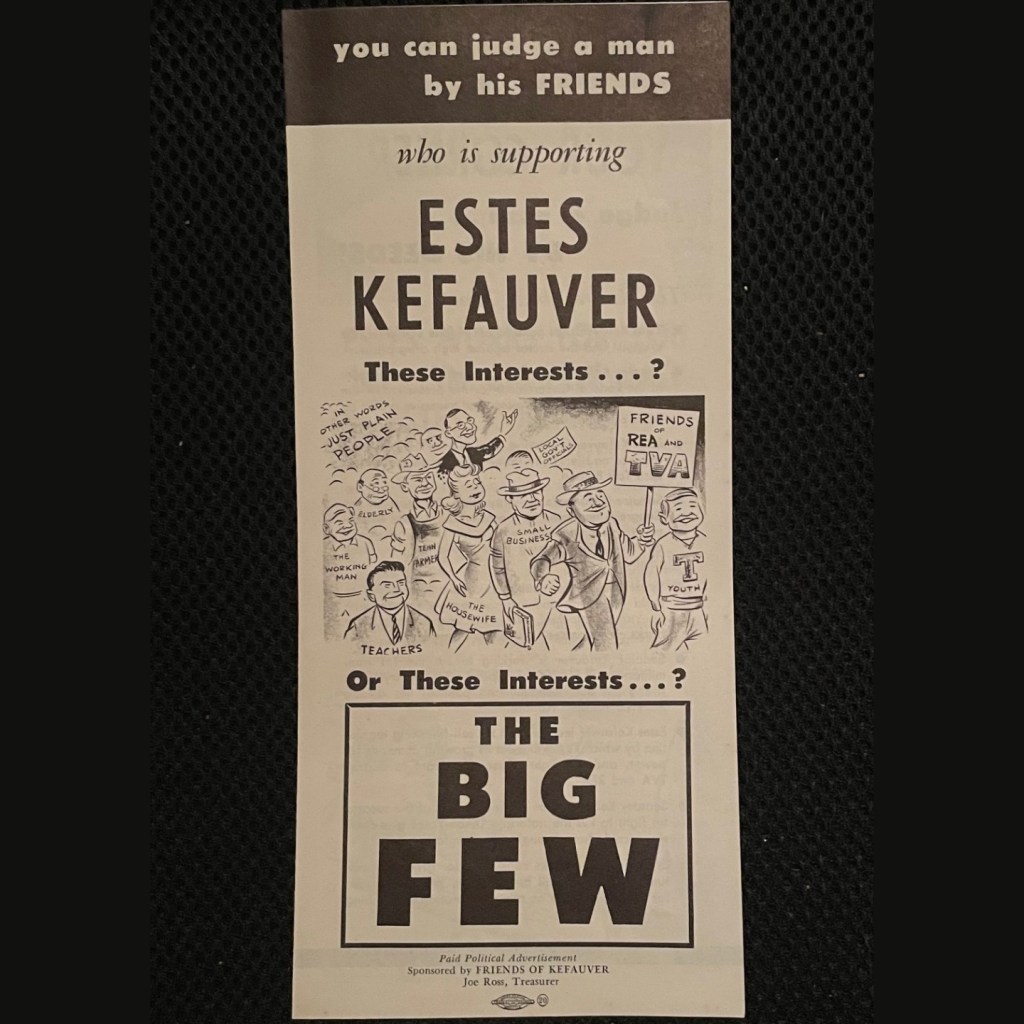

Certainly, Kefauver delivered plenty of that kind of rhetoric. Whether he was running against the Crump machine in 1948, the corrupt political bosses always ganging up against his Presidential runs, or the corporate tycoons who sought to thwart his investigations into monopoly and antitrust later in his career, Kefauver positioned himself as a crusader against powerful interests trying to crush him and, by extension, the people.

But where some populists view the people as marks and dupes to be conned for political gain, Kefauver had a deep faith in the average voter. He had great reverence for our democratic system, the idea that the people decided how our country would be run. Like his fellow Tennessean Andrew Jackson, Kefauver constantly sought ways to center the role of the people in our democracy.

This was why, even before he warmed up to broader civil rights for black Americas, he consistently opposed the poll tax; he saw it as a blatant attempt to keep people from voting. It’s also why he opposed political bosses, who sought to control the nominating process and prevent the voters from choosing their own candidates.

It’s why he ran himself ragged in the Presidential primaries, flying all over the country, shaking hands and making speeches until he could barely stand up. Yes, it was his only realistic path to the nomination, since the party leaders weren’t in his corner. But he also believed sincerely that a candidate for President should have to take his case to the people.

(That’s why the 1952 Democratic convention – where party leaders handed the nomination to Adlai Stevenson, who hadn’t contested a single primary – galled him so much. And it’s why he gained a new respect for Stevenson after he did run in the primaries in ’56.)

One of the hallmarks of true democracy is open debate. It’s no surprise that Kefauver was a champion of freedom of thought and speech, particularly when it came to unpopular worldviews. In his speeches, he talked frequently about the value of dissent. In an era when Communism was considered a dangerous ideology, he stood up for the civil liberties of accused Communists, even when he stood alone.

Kefauver understood that you couldn’t have a real, thriving democracy without people being able to share their honest beliefs, even if they were unpopular. Ultimately, he was confident that the best ideas would prevail in an open debate. If, as Kefauver one said to Teddy White, “you could put a man in jail just for what he was thinking in his head,” that would naturally limit the ideas that people were willing to express.

And as we’ve seen since, ideas that are deemed taboo or off-limits can develop a perverse appeal. If we don’t allow ourselves to talk about unpopular ideas, even to explain why they’re wrong or unpopular, they can flourish in the darkness.

Senate Hearings: Bringing Government to the People

Given Kefauver’s belief in the people, he didn’t want to limit their political participation to the voting booth. He wanted to include them in debates over issues and legislation. That’s where his famous Senate hearings came in.

Kefauver’s hearings were frequently misunderstood in their time. Skeptics considered them a ploy to get his name in the news, especially near Presidential election time. Granted, Kefauver did use the hearings for that purpose; as a savvy and ambitious politician, he would have been foolish not to.

But the hearings also helped bring government to life for the people. For one thing, they offered public accountability. As Kyle Edward Williams wrote in his book The Taming of the Octopus, this was “the form of power at which [Kefauver] excelled: bringing powerful people in front of the cameras and microphones to question them in detail about the organizations they controlled—all in the name of democracy.”

When a crime boss, corporate titan, or government official appeared before one of Kefauver’s committees, they had to justify their actions before the people’s representatives. (Today, when it feels like many powerful people operate with impunity, we could really use a revival of the Kefauver tradition.)

But the hearings weren’t just about holding the mighty accountable. Kefauver sought to inform the people about important issues and inspire them to action.

He knew that issues like organized crime and juvenile delinquency couldn’t be solved by federal laws alone. They also demanded the help of what Kefauver called “an aroused public.” They required the public to care and push for change, whether that meant voting out crooked local politicians, demanding that state and local law enforcement take action against crime, or fostering healthy communities where delinquency couldn’t take root.

Through his hearings, Kefauver sought to make the public aware of important issues and stir them to action. He believed that, thanks to modern mass communication, average people could learn enough about issues to play an active role in democratic government.

“The twentieth-century media of communication provide the back-hills citizen with as much opportunity to inform himself as the citizen living in the shadow of the nation’s Capitol,” Kefauver wrote. He believed that the average person could obtain enough information to participate intelligently in the political debates of the day.

Small is Beautiful

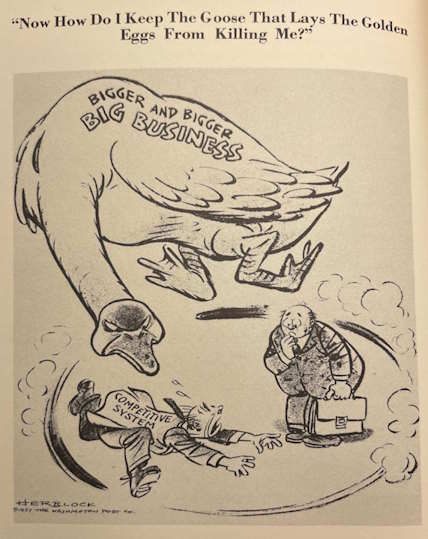

Kefauver understood that in a democracy, concentrations of power and influence might usurp control from the people. He was acutely aware of what Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis called “the curse of bigness,” and he sought to prevent any one group or institution from becoming too powerful in American society.

Like Elizabeth Warren and other modern progressives, Kefauver believed that economic power was tied to political power, and worried about big businesses becoming too big.

He believed strongly in capitalism and the power of free competition, but he worried that when a handful of companies dominated an industry, they engaged in anti-competitive behavior, fattening their own profits at the expense of workers and consumers. Worse yet, they became too big and powerful to effectively regulate or control, and smaller firms couldn’t hope to compete with them.

Big business was a primary concern of Kefauver’s, but it wasn’t the only concentration of power that worried him. He was a supporter of labor unions as a check on corporations’ power to exploit workers; similarly, as a supporter of FDR’s New Deal, he believed in an activist government working to help its citizens. But he was leery of either labor or government becoming too big and powerful.

In a fiery 1947 speech, Kefauver warned of the path to the downfall of industrialized nations. “If we may learn anything from the history of other nations,” he said, “it is that the time schedule reads: first, big business; second, big labor; third, big government; and fourth, collectivism.”

Kefauver believed in a human-scale society, with the individual citizen and his or her well-being at its center. Even with the revolutions in communications, transportation, and economics that paved the way for bigger corporations, bigger cities, and a more interconnected world, he fought against the idea that the average person would become just a cog in the machine.

(One might wonder where Kefauver’s support for Atlantic Union fit into this concern about excessive concentrations of power. I think it fit with Kefauver’s profound belief in American-style democracy. He believed the best way to secure freedom and democracy was to ally with other democratic nations against collectivism. He also saw it as the best way to promote democracy around the world, now that the age of empire was over. Kefauver correctly stood against colonialism, and in favor of people’s right to self-determination around the world.)

Living Principles for a Modern Society

One key difference between Kefauver and today’s right-leaning populists is that, instead of trying to revive an imagined golden age of the past, he was focused on the future. This was Kefauver’s progressive side. One of his great political strengths is that he combined an academic’s ability to understand issues in depth with the populist’s ability to explain them in simple terms for the average person.

From the beginning of his political career, Kefauver was a reformer at heart. He treasured the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, but he never believed that they should be preserved in amber.

Instead, he sided with Thomas Jefferson, who wrote that “laws and institutions must go hand-in-hand with the progress of the human mind. As that becomes more developed, more enlightened: as new discoveries are made, new truths discovered… institutions must advance also to keep pace with the times.”

Kefauver believed that our institutions needed to be updated to keep pace with the maturation of our society. His experience in the House convinced him that many of its archaic practices were not up to the demands of modern society. He co-wrote the book “A Twentieth-Century Congress,” advocating for a number of changes he felt would modernize the legislature.

He studied the Constitution with a trained lawyer’s eye, looking for loopholes, gaps, and edge cases that could create issues in an emergency. When he found them, he proposed solutions, creating procedures in case the president was too sick to serve or giving states the power to appoint acting House members in case of a nuclear strike on the Capitol.

He also sought to reform the executive branch. He proposed new agencies to represent groups that frequently got short shrift, such as consumers and children. He proposed a Department of Science to keep America from falling further behind the Soviets in the space race.

Many of his changes required Constitutional amendments, and so it was fitting that Kefauver became chairman of the Senate subcommittee on amendments. (It’s hard to imagine such a subcommittee today, since the idea of amending the Constitution feels like a pipe dream.)

When it came to fixing problems, Kefauver generally preferred speed and flexibility over perfection. He often proposed broadly-worded bills, with the idea that they could be revised later with the benefit of experience.

This approach didn’t work well with the way Congress operated – numerous veto points and a crowded legislative calendar meant that you often only got one real shot in a generation to address an issue – but it reflected Kefauver’s big-picture approach to things.

As a reformer, Kefauver was a bridge between the FDR New Deal era, which transformed the role and scope of the federal government, and the activists of the late ‘60s and ‘70s, who advocated for change outside the system. It’s no coincidence that there was a flurry of interest in Kefauver’s career in the ‘70s; many of the young activists of that era recognized him as a spiritual ancestor.

Kefauver believed in working within the system, but he was fundamentally a political outsider. And his struggles to deal with an entrenched power structure that fought him every step of the way likely convinced many of the young people who followed that it was better to work outside the system.

A Dream Deferred – or Mission Impossible?

Unfortunately, Kefauver never could to implement his vision as fully as he wanted. He was never elected President, and a lot of his signature legislative ideas were thwarted. Some of them would eventually be enacted after his death; many others were never implemented.

Part of the reason, it must be said, was Kefauver’s own shortcomings. Despite his in-depth understanding of our political system, he never seemed to fully grasp the unwritten rules of the Senate “club,” the log-rolling and back-scratching that allowed you – and your ideas – to get ahead.

Political historian E.E. Schattschneider once noted that “independence is a synonym of ineffectiveness in a game in which teamwork produces results.” He wasn’t talking specifically about Kefauver, but he might as well have been.

Even though Kefauver’s voting record was that of a loyal Democrat, he had a reputation as a maverick and a lone wolf, someone who refused to bend his principles for political expediency. The perception that Kefauver was not a team player hurt him both in his Presidential campaigns and any hopes he had of advancing to Senate leadership.

Another problem, especially earlier in his Senate career, is that Kefauver tried to do too many things at once. His critics called him a publicity hound and accused him of chasing headlines but being unwilling to do the boring behind-the-scenes work. In truth, though, he was just excited by new ideas.

When Kefauver ran for President in 1952, the Washington Evening Star ran a profile on his family life. The article mentioned that he was a tinkerer who loved making gadgets for the neighborhood kids, from stilts to pogo sticks to motorized bikes.

His wife Nancy, however, pointed out that he only enjoyed “making something new – which he rarely has time to finish. He can’t be bothered repairing things.”

The same was often true in his political life. He’d file numerous interesting bills, then jetted off to hold hearings or give campaign speeches and consequently didn’t have time to finish what he started. In his later years, when he settled down and decided to focus on monopoly and antitrust issues, he did his most effective work in the Senate.

So where Kefauver fell short of achieving his vision, it’s in part because he expected too much of himself. But I also wonder whether he expected too much of us.

Kefauver had an idealized view of democracy. He believed that in an open and honest debate, the best ideas would naturally rise to the top. Similarly, he believed that a well-informed citizenry would demand high-quality governance and elect the best and most qualified candidates to office.

He reminds me of Aaron Sorkin, whose romantic view of politics in the movie The American President and the TV series The West Wing earned numerous admirers (and just as many detractors).

At the end of The American President, President Andrew Shepherd (played by Michael Douglas) gave an inspiring speech that basically doubled as Sorkin’s thesis statement. “America isn’t easy,” Shepherd said. “America is advanced citizenship. You’ve got to want it bad, ‘cause it’s gonna put up a fight.”

Kefauver had the same view of citizenship. He knew that citizens who were apathetic, distracted, fearful, or prejudiced might elect leaders who were corrupt, incompetent, racist, or demagogic. (Indeed, he served beside such people in the House and Senate.)

But I’m not sure that Kefauver could have imagined a President Trump. I’m not sure he could have imagined that some combination of cynicism, exhaustion, terror, shallowness, and partisan loathing would lead us to elect – twice! – as our President a man that lacks the basic qualities of a decent human being, much less the qualities of a leader. Or that we would elect a Congressional majority that, instead of holding him accountable or pushing him to improve, alternately cheers him on and cowers in fear of his wrath.

Kefauver had plenty of ideas for making our government and our economy work better for the people they’re meant to serve. But he didn’t have any solutions for a public that didn’t take the responsibilities of citizenship seriously.

Fortunately, there’s still time. Time for us to demand more of our elected officials, to push for a better type of politics, and to fight for a government and an economy that serves the average American, not the other way around. I hope that we can show that the faith of Kefauver – and of countless American leaders throughout history – was justified.

To again quote the fictional President Shepherd, “We’ve got serious problems, and we need serious people.” Here’s hoping that we the people can discover that seriousness before it’s too late.

Leave a comment