It can be difficult to understand the fears of the Cold War era if you weren’t there. If you see a faded sign for a fallout shelter or watch an old “Duck and Cover” video on YouTube, it’s easy to shake your head and dismiss it as paranoid panic.

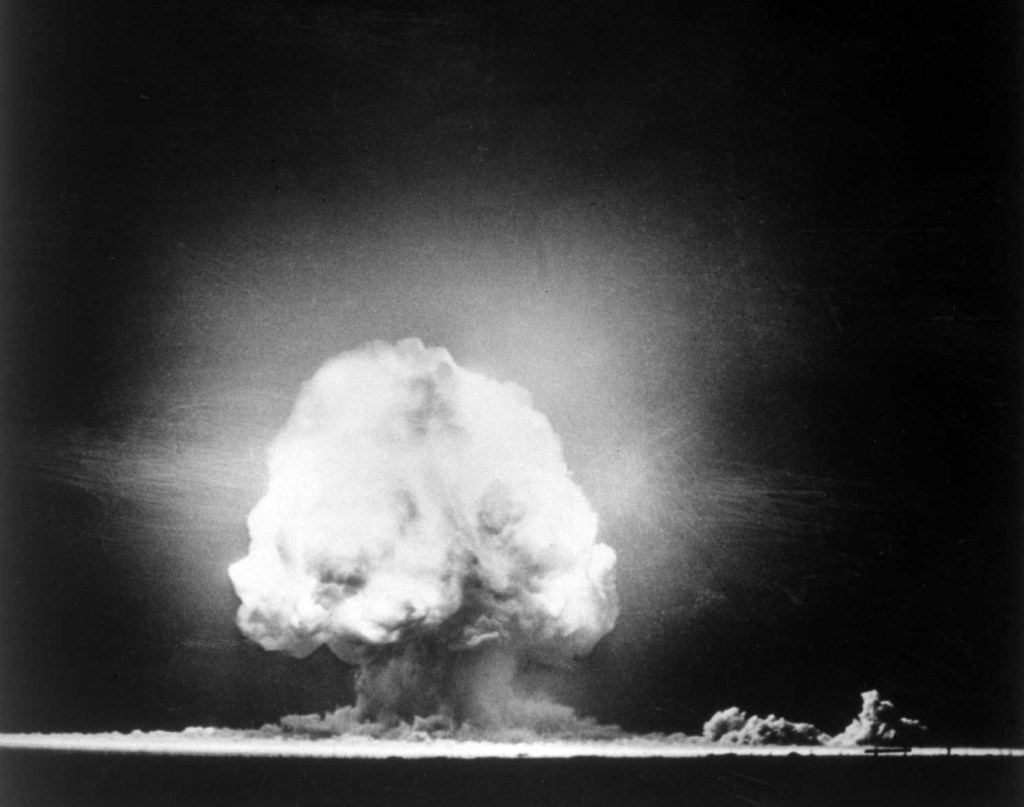

But in the decade or so after World War II, the fear was real. When America dropped the bomb on Hiroshima, we entered a precarious age, where the vast majority of life on Earth could be wiped out in minutes.

To really understand this time, consider a largely forgotten story: Estes Kefauver’s proposed Constitutional amendment allowing America to reconstitute Congress in the event of a disaster. On one level, it was typical Kefauver: identifying a hole in our laws and trying to fix it. But it also speaks to our country’s fumbling attempts to grapple with a new and terrifying reality.

In Case of Emergency, Break Government?

Some people consider the Constitution a holy and sacrosanct document, dictated to the Founding Fathers from God’s own lips. The fact is, it was created by flawed humans; wise, thoughtful, and public-spirited, but human nonetheless.

The document was full of gaps and contradictions. Some are compromises needed to get it passed. Some are oversights that the Founding Fathers could have foreseen but neglected to address. Others are things they never could have foreseen.

This is an example of the latter. The Constitution has no provision for an event that kills a bunch of our political leaders at once. But why would it? Even a mass plague probably wouldn’t have killed that many people that quickly. The Founding Fathers never could have imagined a weapon capable of wiping out an entire city.

World War II changed that. And suddenly, America’s leaders scrambled to devise plans for spinning up most – or all – of a new government from scratch in a crisis.

Congress addressed one issue in the Presidential Succession Act of 1947 (a bill that Kefauver championed). But what if a bomb destroyed the Capitol, leaving much of Congress dead or incapacitated?

For the Senate, there was a theoretical path forward. The 17th Amendment, which mandated the direct election of Senators, allowed state legislatures to empower their governors to appoint a temporary replacement if a Senator died or resigned. Most states had done this. (Not all, however. Even today, five states do not permit temporary Senate appointments: North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, and Wisconsin.)

The House is different. The Constitution permits House vacancies to be filled only via special election, which can take months. If a state was recovering from a nuclear strike, it might take even longer.

In addition, there’s the question of quorum. The rules of the House and Senate both require a majority of members “duly certified and sworn” to be present. But what a majority of members are dead or incapacitated? Could the surviving members even meet to do business?

In a crisis where America would desperately need leadership, the government might be paralyzed and unable to act.

Both houses of Congress began filing bills on this issue as early as 1947. The first to achieve any real traction came from Senator William Knowland of California.

Knowland described the inability to quickly fill House vacancies as ”a very clear weakness in our constitutional set-up which might break down the legislative process of the Government in time of war.”

In 1952, Knowland proposed a Constitutional amendment that would give state governors the ability to make temporary House appointments if more than 145 seats (one-third of the total) became vacant.

A competing proposal from South Dakota Senator Francis Case proposed giving governors the same ability to temporarily fill any House vacancy as the 17th Amendment permitted for Senate vacancies.

The Eisenhower administration endorsed the idea of an amendment, calling the problem a “gap in our national security.” But, in typical Ike fashion, he did not specifically endorse either the Knowland or Case proposal, declaring that Congress could work out the details.

After a perfunctory set of hearings, the Senate Judiciary Committee sent Knowland’s amendment to the floor, where it passed 70 to 1. During the floor debate, Kentucky’s John Sherman Cooper suggested a time limit on the length of the temporary appointments; Knowland replied that the House could consider that when they took up the bill. But the House didn’t take it up, and it died at the end of session.

Kefauver Begins His Crusade

Kefauver took up the cause in the summer of 1953, when he received a fervent letter on the subject from J.P. McCallie, headmaster of a Chattanooga private school.

“Congress could be held responsible by our people for failing to provide against a panic and complete breakdown of our Government in case a bomb should fall on Washington,” McCallie wrote.

McCallie expressed the fear that a nuclear attack would allow Communists to seize control of America. “We do not believe in dictators and demagogs,” he warned. “We hope Congress by neglect will never force us to accept such leadership.”

Kefauver introduced his own Constitutional amendment in January 1954. His bill covered both the House and Senate, giving governors the ability to make temporary appointments when more than half the seats in either chamber were vacant. It also officially defined a quorum in both the House and Senate as a majority of living members, allowing Congress to convene in an emergency.

In typical Kefauver fashion, he made the amendment as simple and straightforward as possible, with details to be filled in later.

When the Democrats took control of the Senate after the 1954 midterms, Kefauver assumed chairmanship of the subcommittee on Constitutional amendments. As chair, Kefauver held a hearing on his proposed amendment – a thorough one, the slapdash hearing that Knowland’s bill received.

Kefauver lamented that his amendment was necessary. “It is a sad commentary of our time that we have obtained a destructive potential necessitating the serious consideration of a resolution such as that now proposed,” he said.

However, he argued that in a time of crisis, America needed a functioning Congress. “[T]he President should have [Congress] available for consultation,” he said, “and, more important, perhaps, the people should have representatives to speak for them in the momentous decisions to be made.”

Ahead of the hearing, Kefauver sent the text of his amendment to all 48 state governors and solicited feedback. Nineteen of them replied with statements of support, which Kefauver entered into the record. In addition, four ex-Governors (Herbert Lehman of New York, George Aiken of Vermont, James Duff of Pennsylvania, and W. Kerr Scott of North Carolina) provided letters endorsing Kefauver’s proposal.

Representatives from the Office of Defense Mobilization and the Federal Civil Defense Administration testified to the need for the legislation. ODM Deputy Director Victor Cooley called it “a very necessary and essential action [that] really, so to speak, puts our house in order.”

Next, Kefauver’s subcommittee heard testimony from several eminent Constitutional scholars: Charles McKinley, President of the American Political Science Association; C. Herman Pritchett of the University of Chicago; and C.D. Robson of the University of North Carolina. That’s where things got complicated.

These scholars agreed that the amendment was vital for the good of the country. However, they had a lot of questions about the details.

For instance, the amendment included the phrase “in the event of a disaster.” Who would be responsible for declaring a disaster? Congress? The President? The state governors? What if those people were killed in the nuclear strike? This seemed a potential stumbling block, and one difficult to resolve in an emergency.

The scholars also questioned how many vacancies should trigger the emergency appointment power. All agreed that half the members was too many; McKinley simply suggested that it should be lowered, while Pritchett and Robson endorsed Francis Case’s old proposal of letting governors make temporary appointments for any House vacancies, as they had for the Senate.

They zeroed in on a clause in Kefauver’s amendment that said that the appointment power would be triggered if there was a majority of vacancies in the House and the Senate. They suggested changing it to say the House or the Senate. (Michigan Governor Soapy Williams made the same suggestion.)

There was also the question of what constituted a “vacancy.” As written, the amendment assumed that everyone affected by the bomb blast would be killed. But what if they remained alive but incapacitated, or unable to make it to Washington to meet? Would such members count against the quorum requirement? If so, could governors appoint temporary replacements for the incapacitated? (Kefauver’s subcommittee colleague Everett Dirksen was the first to raise this point in the hearing.)

Toward the end of the hearing, after reviewing all these possible concerns, Kefauver lamented, “It is remarkable how many complexities a simple proposition can bring up, isn’t it?”

He didn’t give up, however. Instead, he wrote to several more political scholars, providing the text of his amendment and a list of questions raised in the hearings. He included their replies in the record.

Based on their feedback, Kefauver made a couple tweaks to his amendment. He deleted the reference to a “disaster,” instead tying the emergency appointment power to the number of vacancies. He also removed the references to the Senate, since the scholars generally agreed that the 17th Amendment was sufficient. He also made clear that any appointments were temporary, and would last no longer than 90 days, ensure that the seats were filled via election as soon as possible. (True to his populist roots, Kefauver wanted to ensure that the people retained their right to select their representatives, even in a crisis.)

With those changes, Kefauver’s bill made it out of the Judiciary Committee and to the floor of the Senate, where it passed by a vote of 76 to 3. The amendment then went over to the House, which… again took no action. Once again, this critical legislation died.

Third Time’s the Charm?

Naturally, Kefauver wasn’t finished. He refiled his amendment in the next Congressional session. When it went nowhere, he switched tactics. In 1959, he filed a bill combining three Constitutional amendments in one: the emergency appointments amendment, one granting the residents of Washington, DC the right to vote in Presidential elections, and one abolishing the poll tax.

The combined amendment went back to Kefauver’s Constitutional Amendments Subcommittee. He didn’t bother to hold additional hearings, since he’d already explored it so thoroughly in 1955. Instead, the subcommittee reported the bill out to the Judiciary Committee, which voted to move the bill to the floor.

Kefauver prepared a report reminding his colleagues of the bill’s importance. “[T]here need be no departure from constitutional, representative government if precautionary steps are taken in advance of atomic catastrophe,” he wrote, adding that the amendment “is not born of hysteria, but evolves from a desire to protect this Nation.”

He warned his colleagues of “indifference to the dangers of the age in which we live” and said that given “the tremendous destructive power of thermonuclear weapons, it would be the height of folly to leave a constitutional gap of this nature in a representative government such as ours.”

During the floor debate, Kefauver said that solutions like lowering the quorum threshold or waiting for special elections were insufficient. “In times of emergency, as in other times, or possibly more so than in other times,” he said, “our Government should remain a government of the people.”

The Senate approved the three-part amendment by a vote of 70 to 18. The ball was once again in the House’s court. Would they act?

Well, they decided that Kefauver’s three-in-one approach was too much for them to handle. They took out the emergency-appointments and poll-tax parts of Kefauver’s bill and just passed the part giving DC residents the right to vote for President. That ultimately became the 23rd Amendment.

In the following Congress, the House took up the poll-tax ban and passed it separately. That became the 24th Amendment.

But what about the emergency appointments? The House – finally – held hearings on the subject in 1961. Rep. Emmanuel Celler, who had sponsored a House bill along the lines of Kefauver’s proposal, chaired the hearings.

He did his best to move things along. When the hearings got caught up in a debate over how many vacancies should trigger the emergency-appointment power – a subject Kefauver had already hashed out thoroughly in 1955 – Celler cut it off by saying, “I am not going to quarrel with the number.”

He stressed the urgency of cnsuring America’s readiness for an age of potential nuclear war. “Adoption of this resolution,” he said, “would be a demonstration particularly to the enemies of freedom, that we mean to carry on our democratic form of government come what may.”

He added, “[I]t becomes clearer and clearer as tension piles upon tension that to ignore this proposal is to tempt the fates.”

The Kennedy administration lent its support to the measure. Assistant Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach testified that “we do believe that this is an extremely important matter and that it should be provided for by constitutional amendment.”

And then… nothing. Celler’s committee failed to report the bill out to the full House, and it died one more time.

Kefauver’s death in August 1963 robbed the proposal of its strongest champion and pretty much ended any hope of getting the amendment passed. (Stop me if you’ve heard that before.)

Postscript: The Danger Remains

Congress was happy to let the matter drop once Kefauver was no longer around to bug them about it. They ignored the issue for decades, until an actual disaster reminded them that even though the Cold War was over, Congress remained vulnerable.

The attacks on September 11, 2001 shocked and angered Americans. But things could have been even worse. The plane that was forced down in Pennsylvania was reportedly targeted for the Capitol. Suddenly, the possibility of a mass casualty event striking Congress loomed large once again.

Rep. Brian Baird of Washington State drafted an amendment to give governors the ability to make emergency appointments to the House when more than one-quarter of the seats were vacant due to death or incapacitation. Others proposed similar bills of their own.

This time, the House took the lead, with the Judiciary and Administration Committees holding hearings. This led to the formation of a bipartisan working group, headed by Reps. Christopher Cox and Martin Frost, to study the issue and develop recommendations.

The Brookings Institute and the American Enterprise Institute formed a Continuity of Government Commission, whose May 2003 report proposed a variation on the emergency-appointment power that Kefauver originally proposed, covering both the House and Senate.

Alas, it all ended up in the same place. Neither the working group nor the Continuity of Government Commission was ever able to get Congress to vote on their proposals. In 2009, the House made a rule change to speed up the scheduling of special elections to fill vacancies and to declare that a quorum could be as small as a single member.

But the primary problem remained unsolved, and it still is to this day. It likely will remain so until the next time an attack reminds us how fragile our government can be. We can only hope that it won’t be too late.

Leave a comment