I’ve written extensively on this site about Estes Kefauver’s political achievements, and his numerous campaigns. I’ve even written a couple times about his home life and family. But so far, I haven’t devoted a piece to Kefauver’s wife, Nancy. Time to correct that oversight.

Nancy Kefauver was an essential part of her husband’s success. As a busy and rather absent-minded man, Estes Kefauver relied on his wife to keep his life on the rails, manage their household, and raise their four children. She juggled these things with grace and aplomb.

Nancy also helped her husband politically. She wasn’t a strategic partner like Maurine Neuberger. But she frequently joined Estes on the campaign trail, and her wit, sparkle, and charm enchanted the voters. Some of his staffers believed that she was a better campaigner than he was. Even Kefauver’s political enemies admired her.

As Kefauver biographer Charles Fontenay wrote, “Nancy was as near an ideal mate for him as he could have found.”

My Bonnie Lies Across the Ocean

Nancy Patterson Pigott was born in Scotland in 1911. Her father Stephen was a marine engineer from upstate New York. He came to Scotland for a job, and decided to stay and raise his family there.

Nancy was the oldest of four sisters (she also had an older brother). She was a shy, quiet child. Through her teen years, she cultivated interests in art and golf, two pastimes she would maintain throughout her life.

After graduating from the Glasgow College of Art, Nancy moved to London and tried to make a living as a designer and interior decorator. But this was the height of the Great Depression, and she gave up after a year.

In 1934, Nancy and her sister Eleanor went to Chattanooga to visit family. The sisters – especially Eleanor – became hugely popular with the local boys. Toward the end of their stay, the Pigott sisters were set up on a double date with two of Kefauver’s bachelor buddies. When one friend took ill at the last minute, the other one drafted Kefauver to fill in.

Kefauver was technically Eleanor’s date, but he was enchanted with the quiet, red-headed Nancy. She felt the same. The two of them spent extensive time together over the next week, and before the sisters left town, Kefauver asked Nancy to marry him. She agreed, but wanted to talk it over with her parents first.

Once the Pigott sisters returned to Scotland, Nancy and Estes maintained a vigorous correspondence. Kefauver’s ardor and persistence impressed Nancy’s family. “He must mean it,” Nancy’s nurse said. “He’s a lawyer, and he puts it in ink.”

“This young man said he would come over to fetch her in six months, and he came,” Nancy’s father said later. “Quite a forceful affair.”

As promised, Kefauver went to Scotland in August 1935, and he and Nancy married. At the time, Nancy was cheerfully indifferent to politics, both in her native UK and in the US. But she would soon embrace life as a politician’s wife.

Learning the Ropes

Even before Kefauver first ran for Congress in 1939, Nancy helped him by collecting signatures for his reform petitions. “They’d send me every place no one else would go,” she said. “That’s me, always willing.”

Her inherent shyness melted away as she became engaged in the political and social swirl of Chattanooga. And when Estes decided to try for office, she campaigned by his side, shaking hands and urging everyone she met to vote for her husband.

“The type of training I received doesn’t condone subservience,” Nancy said, “but it does emphasize that a woman should make every effort to share her husband’s interests.”

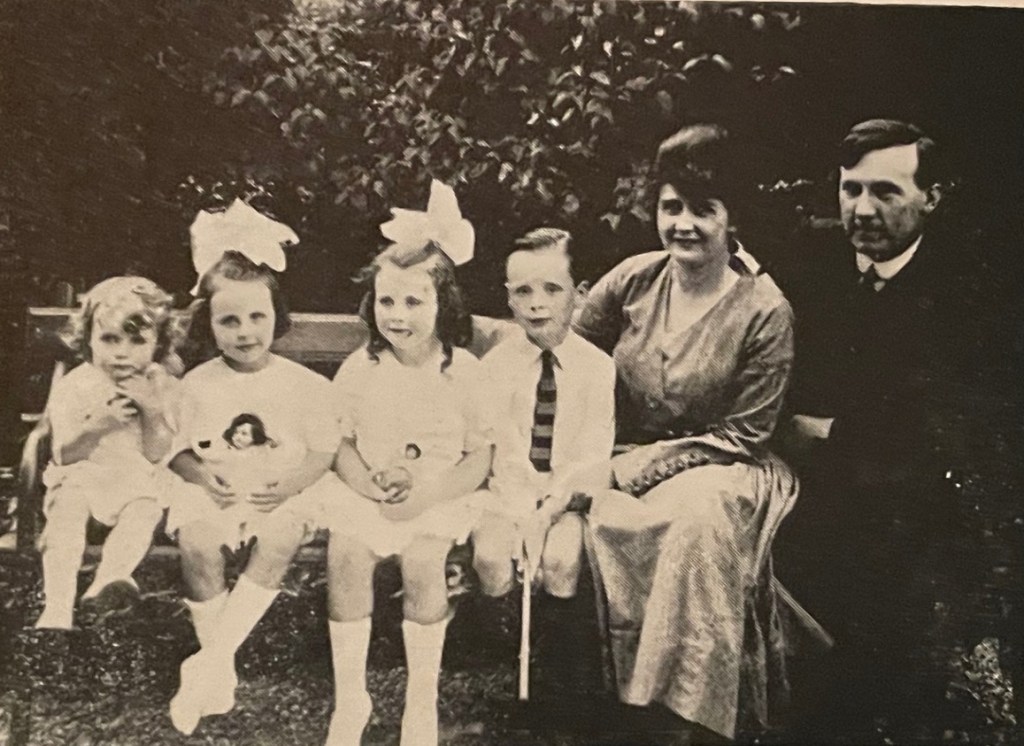

The Kefauver’s early life in DC was like a second honeymoon. Nancy would drive him to and from work every day, spending her afternoons at the Corcoran Gallery. On the weekends, they’d golf together or go sailing on the Potomac. Soon, though, Estes became consumed by his work in Congress, and Nancy had the first of their four children.

By the time Kefauver ran for the Senate in 1948, Nancy had her hands full running a household full of children and animals (including dogs, cats, mice, a turkey, and even a skunk).

She’d also become accustomed to a constant stream of visitors. Kefauver regularly invited friends to dinner or asked them to visit him in Washington, but wouldn’t always mention it to Nancy. She learned to react with cheerful grace when total strangers appeared at her door at any hour of the day or night.

On and off the campaign trail, she kept Estes –apt to get lost in thought and distracted by his work – from accidentally endangering himself.

“When he is hungry Estes will stretch out his hand, and if it happens to fall on a light bulb he may eat it, thinking it is a pear,” Life magazine explained in a 1952 profile. “She keeps the bulbs out of the way… When Estes has to get him to work in the Senate, she drives him there. When he carps about her operation of the car, she waits until his mouth is wide open, then thrusts a sandwich into it, silencing and nourishing him at once.”

It wasn’t under Kefauver ran for President, though, that Nancy was introduced to the country. And America quickly fell in love.

A Storybook Odyssey with an Unhappy Ending

By this time, Nancy was accustomed to campaigning with her husband. So when he decided to try for the White House in 1952, she joined him on his cross-country odyssey.

She followed him through the snow-laden streets of New Hampshire in January and February. She took a ride in a bobsled and spoke French to Franch Canadian audiences. Whenever she and Estes would meet somebody new, she’d jot down the person’s name and address so that the campaign could send a thank you note later on.

And she kept a smile on her face through it all, despite the fatigue and discomfort. (On one occasion, a staffer overheard Nancy whisper to her husband, “Oh, Estes, isn’t there an easier way to die?”)

Nancy dazzled voters with her game-for-anything spirit and her good looks, but also her humor and charm, providing some much-needed lightening of her husband’s image.

Life noted that Kefauver’s “ponderous solemnity suggests a splendidly successful undertaker… It is this aspect of her husband’s personality that Nancy counteracts… [E]verywhere her sparkle relieves his somber sincerity.”

In Florida, the Kefauvers started out campaigning together, then split up so they could cover more ground. On one occasion, Nancy woke up in an unfamiliar hotel and had to find a piece of stationery in the desk in order to figure out where she was.

During Kefauver’s Sunshine State swing, his campaign staff advised to head to Ohio, whose primary was taking place around the same time. He felt he couldn’t leave Florida, though, so he sent Nancy in his place. She campaigned on his behalf in Ohio for several days.

Fontenay reported that Nancy did well in her pinch-hit role. “She knew Kefauver’s stands on public issues and explained them clearly – and could embellish them with a touch of genuine humor Kefauver could not match.” He won every Ohio county where she spoke.

Even Kefauver’s opponents couldn’t help but adore her. During their battle in the Florida primary, Richard Russell – a lifelong bachelor – said that “the only thing Estes has got that I haven’t is Nancy. But it sure is my loss.”

Life, published by the Kefauver-loathing Henry Luce, ran a flattering profile of Nancy shortly before the Democratic convention. Writer Robert Wallace noted that if Kefauver were elected President, “the nation will have one of the most charming first ladies in its history.”

Having survived frostbite, sunburn, and bone-deep exhaustion through the months-long primary gantlet, Nancy was as at least as anxious as her husband when the convention rolled around.

“It seems strange that after all the work you put in on a nomination, everything can be decided in just a few days,” she told columnist Drew Pearson. “We tramped through the snows of New Hampshire, we stumped almost every town in Florida, we toured all over California, and almost every other state, and now, in just a few days, all that work will either pay off or be washed away.”

Both Nancy and Estes were heartbroken when he lost the nomination to Adlai Stevenson. She shut down any of her husband taking the Vice Presidential slot with a rare undiplomatic statement: “Tell them to go to hell!”

There’s No Second Time

The experience of campaigning together in 1952 was a positive one for both Kefauvers, despite the bitter ending. Pearson privately credited the campaign with strengthening the couple’s marriage. “Nancy has not only been one of Estes’ biggest assets,” he wrote in his diary, “and he not only has appreciated it, but the campaign has brought them together as never before.”

Nancy also enjoyed the national adulation. “I felt like I was walking on air when the crowds used to sing out ‘Where’s Nancy? We want Nancy!’,” she said later. “I felt so gratified and helpful. I was sure I was doing the best thing possible for Estes towards attainment of his goal.”

After the campaign, however, Nancy learned of ugly rumors about her that trailed behind the headlines: that she was a grasping climber who had already made plans to redecorate the White House, and that she planned to divorce Estes if he lost the election. These rumors were completely false, but still hurt her deeply.

Worse yet, Nancy said, upon returning home “I found four unhappy, bewildered young children. Their friends were sorry for them because they were left alone so much.”

Stung by these revelations, Nancy threw herself back into the role of wife and mother. She also opened an art studio in Washington with a friend of hers. From an initial group of six students, they eventually grew to a class of 100.

When 1956 rolled around, and Kefauver contemplated another Presidential run, both Nancy and the kids were firmly opposed.

When he decided to run anyhow, Nancy made her displeasure apparent. During his campaign kickoff announcement, she sat in the back row wearing dark glasses and a scowl. When he called her up front, she remained unsmiling as she answered questions from reporters.

She had made clear to Estes that she would not be going on any lengthy jaunts away from home this time around. She reluctantly agreed to support events near home, but insisted that she be home with the children at night.

She acknowledged that Kefauver would “like me with him when he travels around the country, but he’d dislike more coming home to a bunch of juvenile neurotics!”

Estes tried to put a positive spin on the situation, saying that she would “do her share, but she won’t be able to get out on campaign trips as much as she did before. The children are older and badly need one of us.”

Nancy remained upset through the early stages of the campaign, and didn’t hesitate to make her displeasure known. “I don’t know why he wants it,” she said of her husband’s quest. “I try to figure it out myself. He’s not ambitious about anything else – money or material things. I think he’s always been aiming at a goal a little higher.”

As time on went, though, she seemed to reconcile. “I know Estes,” she said. “He loves his children but he also loves the life he has set out for himself – public life. To leave that would destroy him. He’d rather be in there plugging away – win, lose, or draw – than doing anything else in the world.”

She held firm to her promise, however, and Kefauver trod the primary trail largely without Nancy. It’s likely no coincidence that he came up short against Stevenson.

She did attend the convention. When Stevenson threw the VP nomination open to the floor, Nancy urged Estes to run (because, she said, “I knew retreat would destroy him”). She watched anxiously as the race became a duel between her husband and John F. Kennedy. Having learned the cruel lesson of 1952, she refused to celebrate until it was over.

Even after Estes clinched the VP nomination, Nancy held firm to her promise to stay away from campaigning. Her absence was conspicuous (particularly compared to her neighbor and friend Pat Nixon, who campaigned actively with her husband). During the fall, there were multiple stories speculating about whether or when Nancy might go back out on the trail. America missed her.

She finally agreed to campaign during the final week. She met Estes in Boston and traveled with him from there. In Rhode Island, she again gave a speech in French for the benefit of a French Canadian audience. Kefauver gleefully welcomed his “secret weapon” back to the stage.

This time around, she wasn’t bothered much by the election loss. When the old divorce rumors popped up again, Nancy brushed them aside. “It was spread about some last campaign and got more play this time, I guess, because I campaigned less.” She said she’d been absent from the trail because “stumping the country is too hard on your children and your kidneys.”

By His Side Until the End

After the 1956 campaign, Nancy continued her life as a mother, art teacher, and homemaker extraordinaire. She made her own slipcovers and drapes, and took care of basic carpentry work around the house. She even slipped in an occasional round of golf, modestly claiming, “I occasionally break 90.”

The Kefauver home in Washington’s Spring Valley neighborhood remained a social hub for adults and kids alike. “Spring Valley knows the Kefauvers as people who are wonderful with their children,” wrote columnist Liz Carpenter, who lived nearby. “Their yard has two playhouses, a sandpile and a gym set, and it is the gathering spot for most of the children in the neighborhood.”

When Kefauver was stricken with the heart condition that would kill him in August 1963, Nancy was vacationing in Colorado with their two younger daughters. When she learned that her husband had been diagnosed with an ascending aortic aneurism, she booked the first flight back to DC that night.

Kefauver wouldn’t let the doctors start operating until Nancy was by his side. He died at 3:30 in the morning, as her plane was touching down. Nancy later said that she sensed his passing.

She chose the words “Courage, Justice, and Loving Kindness” for his tombstone.

After Kefauver, A Champion of the Arts

After Kefauver’s death, prominent Democrats in Tennessee urged her to run for his Senate seat, but she had no interest. “After 25 years of active political life, I’ve just had it,” she told a reporter in 1964, adding that “a true politician has to be dedicated as Estes was. He was a natural politician. He loved campaigning.”

She also never expressed interest in remarrying, deflecting questions by saying that “I had too perfect a marriage.”

She did need a job, though; Estes left behind a modest estate, and her art school wasn’t a full-time business. So in November 1963, President Kennedy named her coordinator of the State Department’s Art in Embassies program.

She’d conceived the idea for the program while visiting embassies with Estes. “As a practicing artist,” she said, “it just killed me to see all that marvelous wall space going to waste.”

In her new role, she coordinated displays of American art at embassies around the world. “We like to think of this program as backing up our diplomacy with our cultural image,” she explained, adding that “we’ve not given the average people of these countries any real knowledge of American culture.”

Originally conceived as a part-time position, it quickly became a full-time duty.

In late November 1967, Nancy was attending a dinner for Senator Everett Dirksen in DC when she collapsed and died of a heart attack. She was just 56 years old.

Postscript: The Wanderer

I can’t close out this piece without addressing the elephant in the room: Kefauver’s infidelities. He slept with numerous other women throughout their marriage, including on the campaign trail when she wasn’t present. How can we reconcile his wandering with the portrait of an apparently loving marriage?

I can only point out that standards for male behavior were different in that era. The affairs of other politicians of Kefauver’s era, like Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, are well known at this point.

Nancy was aware of Estes’ affairs, at least to an extent. She generally tolerated them and did not consider them a reflection on her. Carol Harford, her longtime secretary, said that Nancy “would invite the gal of the moment over to dinner or include her in some social function they were having.” She told close friends that she felt Estes could only truly relax in the company of women.

There were at least a couple times where Nancy put her foot down. Once, a very attractive women applied for a job as Estes’ secretary. Nancy instead hired her as a model for a painting. She spent so long working on the painting that her husband eventually got tired of waiting and hired another secretary.

On another occasion, Kefauver hired a female staffer; shortly after Nancy found out about her, she was fired and exiled to Europe.

For all Kefauver’s sleeping around, however, Nancy was the only true love in his life. As his receptionist Henrietta O’Donaghue put it: “The only woman he ever really loved was Nancy. She was everything to him.”

Leave a comment