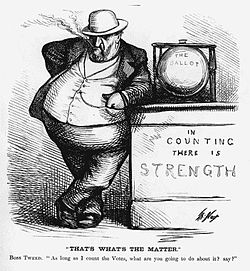

Boss Tweed, infamous leader of Tammany Hall, knew a thing or two about wielding power. He was infamous for pulling the strings of New York City government behind the scenes. But Tweed was a supporter of democracy – up to a point.

“I don’t care who does the electing,” he once said, “so long as I get to do the nominating.”

Boss Tweed was gone by the time Estes Kefauver came on the scene, but Tammany Hall and other urban political machines were still alive and well. In 1952, even though Kefauver nearly ran the table in the primaries, the bosses and other party leaders blithely tossed him aside at the convention and nominated Adlai Stevenson, who hadn’t even been a candidate.

Public outcry at the conduct of both conventions in 1952 led Congress to consider a Constitutional amendment that would have established a nationwide Presidential primary system.

Unsurprisingly, Kefauver –a political reformer by nature who had experienced the unfairness of the convention system firsthand – led the charge in favor of this amendment. Unfortunately, his crusade might have inadvertently hurt the cause by turning it into a referendum on his candidacy.

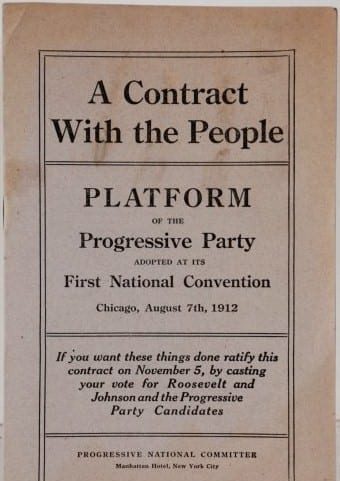

Primaries: A Blast from a Progressive Past

Kefauver wasn’t the first to suggest a national presidential primary. In 1913, President Woodrow Wilson included the idea in his first message to Congress.

The Progressive political movement, of which Wilson was a member, fought to give the people a greater role in political decisions. Wisconsin was the first state to establish a Presidential primary in 1905. By the time Wilson was elected in 1912, twelve states were holding primaries; four years later, the number had swelled to 20.

As the Progressives faded away, however, so did interest in primaries. In 1924, 23 states held primaries; by the time of Kefauver’s run in 1952, only 16 states still held them.

So why did the conventions become controversial? In part, it was because for the first time in decades, both parties had an open race for their nominations.

There was another key factor, however: television. For the first time, the average American could watch the sausage being made in real time. And they didn’t like what they saw.

On the Democratic side, they watched the most popular candidate – the one who had crisscrossed the country to whip up votes – thrown overboard. On the Republican side, they saw supporters of Dwight Eisenhower and Robert Taft engage in nasty clashes over virtually every aspect of the proceedings.

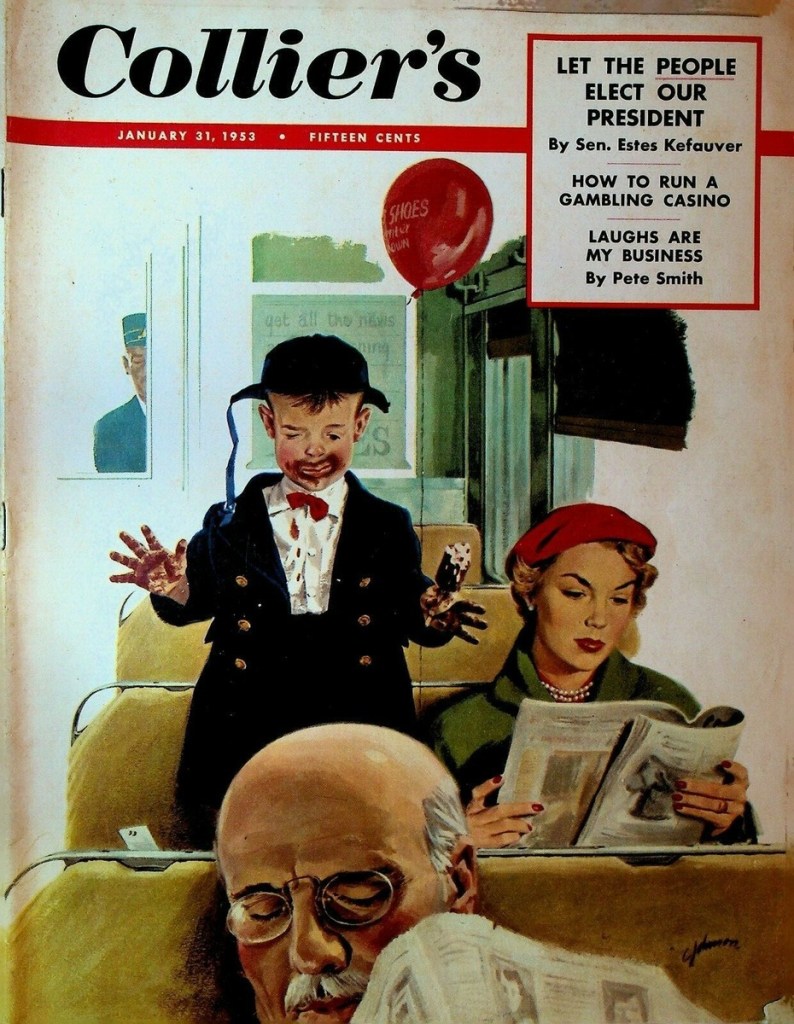

As Kefauver wrote in a Collier’s magazine article in January 1953, “TV has brought the national convention into the living room of the American home, and has exposed it for the undemocratic spectacle that it is.” He believed that this would create the public pressure needed “to break the hold of the bosses and others who make decisions in smoke-filled rooms.”

Kefauver Pitches His Plan

With that in mind, Kefauver filed a proposed Constitutional amendment allowing Congress to establish primaries in each state to select each party’s nominees for President and Vice President.

He deliberately kept the bill as open-ended as possible. He figured that creating a nationwide primary system would involve trial and error, and he didn’t want prescriptive language in the amendment that might lock the country into a flawed or unworkable solution.

That didn’t mean Kefauver didn’t have an idea how the primaries should work. He laid out his proposal in the Collier’s article, which he placed into the record during the 1953 hearings on his amendment.

He envisioned primaries in every state, with uniform rules for delegate selection. At the time, even in the states with primaries, the rules were all over the place. Some bound their delegates to the winner of the primary. Others bound them only for the first round of convention voting. Still others didn’t bind them at all, meaning the primary was a glorified straw poll. (Florida, for some reason, had a straw-poll-style vote and a separate vote to allocate delegates a couple weeks later.)

In Kefauver’s preferred approach, each candidate would receive delegates in a given in proportion to the percentage of votes received in that state. Alternately, he was open to the Wisconsin approach, where the leading vote-getter received a group of at-large delegates, and then the winner of each congressional district got the delegate for that district. The number of delegates from each state would be determined by the number of votes that party’s candidate received in the last election.

Each candidate’s delegates would be bound to support their candidate at the convention until he either dropped out or fell below 10% of delegate votes. The winning candidate would be the one who received a simple majority of delegate votes (not the two-thirds majority then required).

This might sound like a recipe for deadlocked conventions, but Kefauver had considered that possibility. If there was no winner after 10 rounds of convention voting, all delegates would be released from their pledges… but could only vote for one of the candidates who finished in the top three nationally.

(This was intended to weed out the then-popular “favorite son” practice, where a state’s delegates would be pledged to a local leader, providing that leader with leverage to extract favors at the convention in exchange for his delegates.)

Once the Presential candidate was selected, the delegates would then select the Vice President… but again, they could only choose among the three candidates (apart from the Presidential nominee) who had received the most national votes. (One obvious theme: Kefauver wanted to incentivize entering as many primaries as possible.)

Kefauver felt it was important that the Vice President be a serious, qualified candidate who could step into the Presidency if needed (as opposed to someone chosen for purely political or geographical reasons).

By restricting the choice to candidates who had done well in the primaries, he reasoned, you ensured a VP who the voters had found both qualified and appealing. Also, presumably, any skeletons in the VP’s closet would have been exposed during the primary.

Kefauver proposed that all the state primaries occur on the same day in August. (This would prevent the scenario we see today, where the early primaries effectively winnow the field before most voters have a chance to weigh in.) The conventions would then occur in September, and general election campaigning would be limited largely to October.

“I would like to see all campaigning elevated to a less strenuous, more intellectual level, with less wear and tear on the candidates,” he said. “I have never seen any sense in practically killing off our Presidents before we select them, and I am sure that the American people do not want that.”

Rolling with the Tide of History

When testifying about his proposal to the Senate Subcommittee on Constitutional Amendments, Kefauver anticipated several possible criticisms of his plan.

One had to do with holding all the primaries at once. “Critics may argue that the strain of running in 48 separate primaries might kill a candidate,” he acknowledged. “I do not think so, particularly with the advent of television. The campaign in each State need not be as intense as the full-dress presidential campaign.”

To those who argued that a national primary would naturally favor candidates with strong organizations and/or lots of money, Kefauver cited his own campaign from 1952. “Certainly with scant organization and very little money,” he told the subcommittee, “I fared well in the primaries I entered.”

He pointed out that the idea was widely popular among the public, citing a Gallup poll performed after the 1952 conventions that showed 73% of respondents favoring a switch to a national primary system (vs. only 16% who favored the existing convention system).

He also argued that his proposal continued the overall historical trends of giving more political power to the people. From the removal of property qualifications for voting to the 14th and 15th Amendments to the direct election of Senators and woman suffrage, America had slowly but surely moved toward expanding voting rights.

“The more the people have a chance to speak their minds, the closer we get to grassroots opinion and desires, the better our democracy works,” Kefauver said. “In this period of struggle between the democracies and the dictatorships, the choice of men to lead our Nation is too important to leave solely in the hands of politicians.”

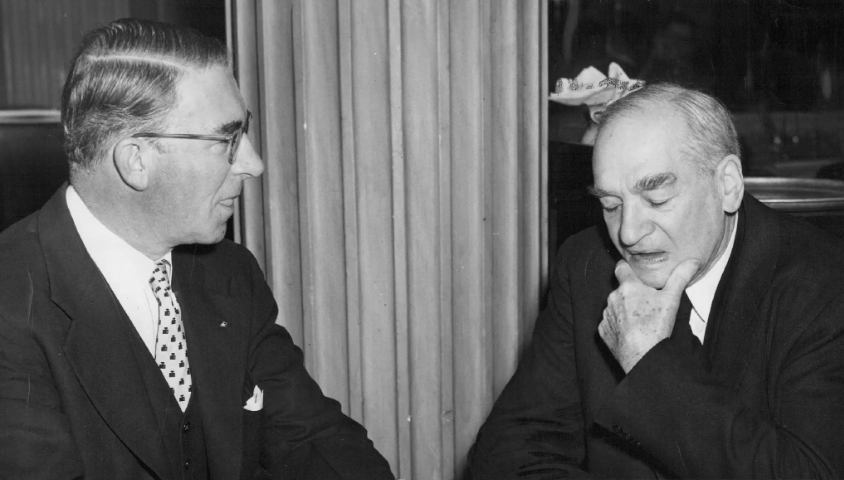

Kefauver was supported by Florida Senator George Smathers, who had filed his own bill proposing a national Presidential primary. “How much pride can be taken in the supremacy of our system over that of the dictatorship,” he argued, “when we give the right to vote to the people, but only on candidates that have been previously selected and handpicked for them through the machinations of party leaders and backroom bosses?”

The Hearings Run Amuck… and Kefauver Shoots Himself in the Foot

Given that there were multiple Senators pushing a national primary amendment, and the fact that the Constitutional Amendments Subcommittee included Kefauver and was chaired by William Langer, a friend of Kefauver and fellow independent-minded reformer, it seems like the amendment’s chances were good. Yet it never got out of the subcommittee. Why not?

Part of the problem is that the subcommittee tried to tackle too many issues at once. The 1953 hearings covered not only the national primary proposal, but also several ideas for Electoral College reform, including one from Kefauver.

Reading the transcripts of the hearings, it’s clear that they were a mess. Kefauver was frequently asked questions about his Electoral College proposal when he was trying to testify about his national primary proposal, and several subcommittee members – Langer very much included – seemed to be confused between the two.

Also, in general, the subcommittee members were much more interested in Electoral College reform, and the national primary proposal got shunted to the side.

Another problem, frankly, was Kefauver himself. Although he was sincere in his proposal, it was easy for his critics to dismiss it as a self-serving attempt to boost his own Presidential prospects.

He didn’t do himself any favor with his Collier’s article. In addition to laying out his primary proposal, he also recounted his experience at the 1952 convention. That part of the article was laced with bitterness at the “unscrupulous kingmakers,” “smug, self-satisfied advocates of the status quo,” and “machine stalwarts” who conspired to deny him the nomination.

He self-righteously insisted that the bosses hated him because of his “call for new, young, vigorous leadership” and because as chairman of the organized-crime subcommittee, “I carried out my sworn obligation to uncover facts where I found them, without regard for party politics.”

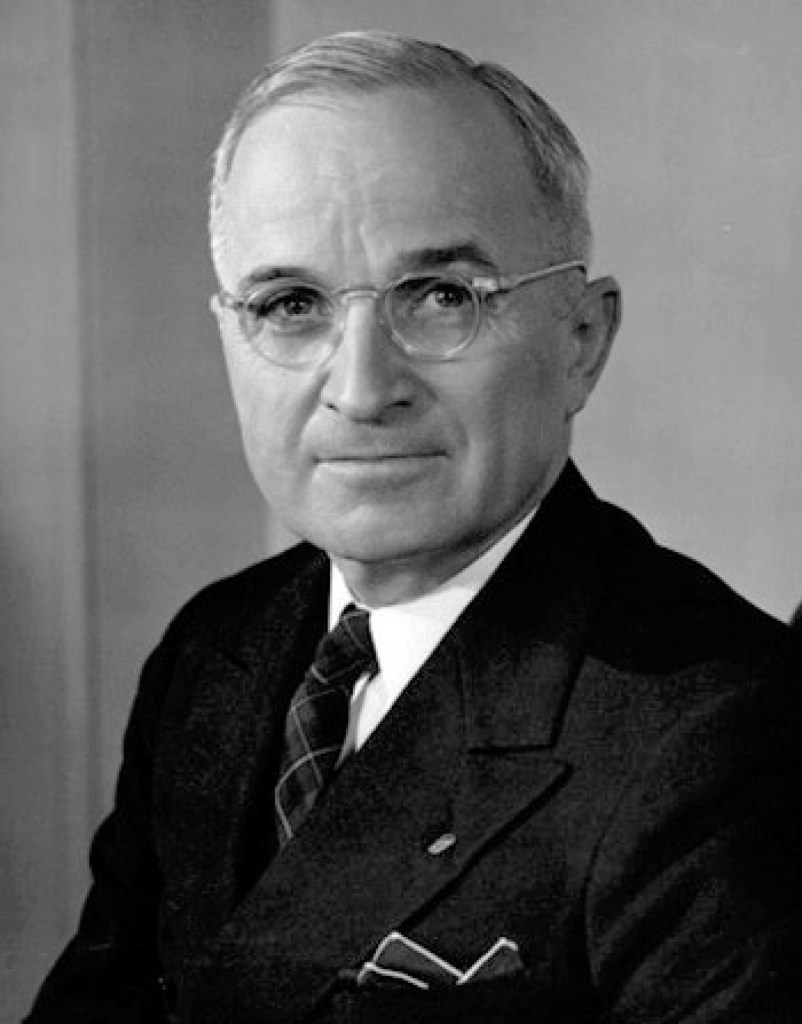

He dismissed Stevenson as “virtually a political unknown on the national scene“ and claimed that Harry Truman’s campaign for Stevenson “placed the efforts of the Presidential nominee himself into such a peculiar and undignified second billing.”

In short, it was a magnificent exercise in bridge-burning. Democratic leaders who already distrusted him were probably ready to crush him at all costs after reading that article. Certainly, they weren’t going to do him any favors by passing his national primary amendment.

A Change Comes… Eventually

After his primary proposal died in the subcommittee in 1953, he brought it back in 1955. This time, he had the advantage of chairing the Constitutional Amendments Subcommittee. However, everyone knew that he was planning to run again in 1956, so the resentments from 1953 were still a problem.

After that, he wisely dropped the issue until 1961, when his own Presidential ambitions were over. This time, his testimony to the subcommittee was free of references to “bossism” and made only passing references to his own campaigns.

“[T]he long-run trend has been toward the gradual democratization of our electoral system,” he reminded his colleagues. “It remains now to democratize our methods of nominating and electing the President and Vice President.”

Unfortunately, his effort met the same fate it had in 1953 and 1955, failing to make it to the Senate floor. Kefauver’s death in 1963 deprived the issue of its chief champion (although Smathers kept trying).

The next major push for a national presidential primary came in 1968, but it again took a back seat to the effort to abolish the Electoral College. After that, facing a backlash from voters angry about Hubert Humphrey’s nomination, the Democrats convened the McGovern-Fraser Commission, which took the nominating power away from the power brokers and gave it to the people.

Would it have been better if the national primary amendment had passed? Perhaps. The idea of holding all the primaries on this same day – and standardizing the process for allocating delegates – is appealing. It would be nice not to have the nominee virtually decided after the first few contests.

On the other hand, I think Kefauver underestimated the rigors of a national primary. I also think he underestimated the way it would benefit well-funded candidates with organizations.

In a lot of ways, Kefauver’s national fame from the organized crime hearings gave him an unusual advantage in 1952 that compensated somewhat for his lack of money and staff. I think it would be more plausible today, with the rise of small-dollar donors and the use of the Internet as a campaign tool.

That said, Kefauver had identified a real issue. The era of party bosses controlling the nominations was indeed coming to an end; the people were demanding a change. And that change did come… just not in time to help the Senator from Tennessee.

Leave a comment