Last week, we talked about how the GOP, with a new governing trifecta in 1953, wanted to use it to pin blame for the Korean War on the Truman administrations. General James Van Fleet’s accusations that he didn’t have enough ammunition to conduct the war properly gave Congress an opening to hold hearings.

But it wasn’t a partisan slam dunk. Van Fleet wanted to use the hearings to make the case for escalating the war. President Eisenhower wanted to make the case for cutting defense spending. And Estes Kefauver, a member of the subcommittee, wasn’t going to let the GOP spin the hearings their way.

This week, we’ll examine the hearings themselves.

Give Me Back My Bullets

When the hearings began, Van Fleet came out with guns blazing. He regaled the subcommittee with tales of how the supposed ammo shortage prevented him from slaughtering the enemy.

He lamented “the Chinaman’s tactics of mass attack, using manpower to overrun you, taking tremendous losses, but always getting on the objective,” concluding that “the only way you could mow that down is with artillery; you have got to mow it down.”

Van Fleet that the Chinese and North Korean forces made “beautiful targets, like potshooting at ducks, wonderful opportunity, providing we had the firepower to mow it down. But we did not have the firepower.”

He told the subcommittee that if he’d been allowed to attack aggressively to the north in the summer of 1951 (an attack that was vetoed by his superior officers), he would have scored a major victory. He claimed that the decision to limit the war allowed the enemy to choose “the time and place of any violent battle and make plans accordingly.”

Van Fleet’s assertions were backed up by Ned Almond, Douglas MacArthur’s former chief of staff and commander of X Corps. Almond called Van Fleet’s testimony “very sound and complete” and said that the only acceptable option was “that which would fully support those elements in combat as long as necessary, as long as the enemy wills it.”

Almond said that shortages had existed in Korea before Van Fleet arrived, and that on multiple occasions, previous Far East Commander Matthew Ridgway had to “delay offensive action pending the build-up of enough ammunition.”

The rest of the subcommittee was inclined to let Van Fleet and Almond sail through without serious questioning, but Kefauver had other ideas.

He asked Van Fleet what kind of ammunition, specifically, the US forces lacked. The general replied that there were “critical shortages all the way through.” This was a dramatic escalation of his earlier claims, which had been that his forces had been short of hand grenades and 155mm Howitzer rounds. But Van Fleet seemed indifferent to the contradiction, or the fact that he might be undermining his own credibility.

Kefauver asked both Van Fleet and Almond how they determined what an “adequate” supply of ammunition was, and what constituted a shortage. Van Fleet cited the artillery’s use of ammo in France during World War II as a benchmark; in response Kefauver pointed out that the battle situations were different, and supplying the forces in France was a completely different matter from supplying them in Korea. Almond conceded that the determination of “sufficient” ammunition involved negotiation and compromise between commanding officers.

Kefauver also challenged both officers on the existence of an ammo shortage. He pointed out that when the Army began rationing the use of ammunition in the summer of 1952, Van Fleet himself assured reporters that “gun crews had all they needed,” and that the purpose of rationing ammunition was “to prevent waste.”

Van Fleet had s simple response for that: He was lying in 1952. The Army was rationing ammo, he said now, because “there was not sufficient quantity being produced or sent to the Far East to permit the guns to shoot it at a greater rate.” He’d lied back then, he claimed, to fool the enemy and to avoid harming his troops’ morale.

With Almond, Kefauver cited a famous moment from his command of X Corps when US troops met the Chinese at the Yalu River, and Almond retreated from the river back to the port of Hungnam, where they could be evacuated. Kefauver asked Almond if he’d retreated due to a lack of ammunition. Definitely not, Almond replied; in fact, one of the major logistical challenges of the retreat was getting the army’s 324,000 tons of supplies, including a “great quantity” of ammunition, out of Hungnam.

Kefauver’s questioning wasn’t enough on its own to discredit Van Fleet’s claims of a shortage. But he would soon receive backup from an unexpected corner.

Ike Launches a Counteroffensive

It didn’t take long for President Eisenhower to decide he’d had enough of the hearings. The ongoing discussion of supply shortages was bad for his case to cut defense spending, and Van Fleet’s open campaign to widen the war was complicating his desire to end it. So on March 26th, Eisenhower held a press conference that cut both Van Fleet and the subcommittee off at the knees.

He told America that there was no ammunition shortage. He said that when he’d gone to Korea in December 1952, he’d asked the officers about the ammo supply, and they’d told him “emphatically that the present situation in ammunition is perfectly sound.” He added that ammunition rationing during war was nothing new; he himself had ordered it during World War II, to prevent waste.

As for Van Fleet’s claims of a shortage, Ike gave them the back of his hand. He said that commanders were always complaining about something, and that “no commander ever has all he wants.”

Eisenhower’s comments seemingly obliterated the justification for the hearings. Even Almond, whose testimony continued after Ike’s remarks, asked whether there was a point to the hearings, since the Commander in Chief had stated that there were no shortages.

In response, the subcommittee majority stuck their fingers in their ears and told the President “La-la-la, I can’t hear you!”

Margaret Chase Smith, the subcommittee chair, replied to Almond’s question by saying the hearings were to “get to the bottom” of the ammunition controversy. Anyway, the real point was to discuss defense policy reform, and & “what safeguards should be established to prevent future such shortages.” (Her statement conveniently elided the fact that the actual shortage in question didn’t exist.)

An Ammo Expert Fires Back at Van Fleet

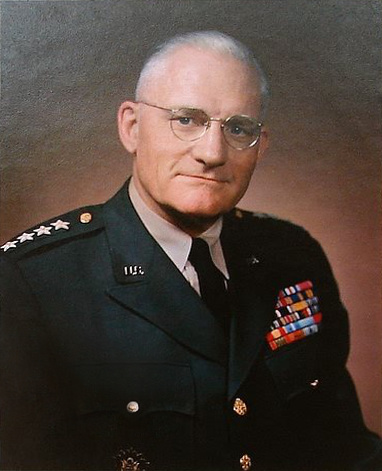

Van Fleet’s argument took another body blow from the testimony of Williston Palmer. General Palmer was arguably America’s foremost expert on ammunition at the time. He was an expert artilleryman who had commanded the VII Corps during the Normandy invasion. He’d since become the Army’s Assistant Chief of Staff for Materiel, in charge of maintaining the ammunition supply.

Palmer mowed down Van Fleet’s claims of an ammunition shortage. He pointed out that the Army calculated its supply of ammunition in terms of the number of days’ supply available, not the number of rounds. This meant that if officers in the field increased the approve rate of daily artillery fire, they could essentially create an artificial “shortage” out of nowhere.

Palmer provided an example from Korea. Between September and October 1951, the Army’s supply of 105mm Howitzer rounds increased from 3.6 million to 4.35 million. However, because the officers had increased the number of guns and the approved rate of fire, the number of days’ supply actually went down.

The general added that US and allied troops had enough firepower to “outshoot the enemy by an impressive 10 rounds to 1,” even though the US was supplying its forces from across an ocean, unlike the Chinese.

Palmer had also served as commander of X Corps in Korea, so he’d seen Van Fleet’s use of artillery up close. To put it kindly, he was not impressed. He told the subcommittee that under Van Fleet, there was “an unnecessary amount of firing going on during a very static situation.” Displays like the “Van Fleet Day of Fire” may have looked impressive, but they didn’t actually alter the course of the war.

Coming on the heels of Eisenhower’s dismissal of the situation, Senator Smith recognized that Palmer’s testimony was a huge problem, so she swung into red-alert mode.

The next day after Palmer’s testimony, Smith opened the proceedings by endorsing Van Fleet’s (by now discredited) claims of a shortage. Even if he had somewhat exaggerated that scope of the problem, she said, “there is not any room for the argument that no shortage existed.”

At this point, you’d be forgiven for thinking the subcommittee might have quietly folded its tent and slunk away. But as Smith’s statement suggested, they had another plan in mind. We’ll find out what it was in next week’s final installment.

Leave a reply to Kefauver and the Korea Ammo Hearings, Part 3: Inconclusive Conclusions – Estes Kefauver for President Cancel reply