Estes Kefauver was not a typical politician. This was true in many ways; one was his unwillingness to play the expected political games. This hindered him repeatedly throughout his career.

For instance, his unwillingness to follow the clubby conventions of the Senate blocked his path to leadership and left him an outsider among his peers. And during his Presidential runs, his open ambition for the job and unwillingness to kowtow to party leaders thwarted his hopes to the nomination.

A November 1955 column from nationally syndicated political writers Joseph and Stewart Alsop highlighted Kefauver’s unorthodox approach to politics. Kefauver talked with unusual frankness to the Alsop brothers about the possibility of running for President in 1956.

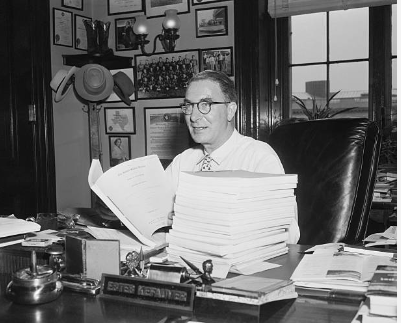

Everyone was certain that Kefauver was going to run. The general assumption was that he’d been planning his 1956 campaign practically since his 1952 run failed. These assumptions were well-founded. Kefauver had been trying to position himself as the leader of the Democratic opposition throughout Dwight Eisenhower’s term. Throughout 1955, he had been raising his national profile by leading Senate investigations into juvenile delinquency and the Dixon-Yates contract with TVA.

Given all that, it was a shock to see the Alsops write, “It is entirely possible that Senator Estes Kefauver will not be a candidate for the Democratic Presidential nomination, although the betting is certainly the other way.”

At this point in the campaign cycle, it wasn’t uncommon for candidates like Kefauver to proclaim they were on the fence about running, even if they were certain to do so. But there was a script for candidates to follow in such situations.

They’d claim to be focused on their current jobs, and the idea of a Presidential run was only dimly on their minds. They might possibly consider such a run, but only if they felt the people or the party calling them to serve. They wouldn’t mention grubby practical concerns like fundraising. And they absolutely, positively wouldn’t talk about any of the behind-the-scenes machinations involved in obtaining the nomination, in an era where the party bosses in smoke-filled backrooms still had sway.

Kefauver took that script and threw it right out the window.

Instead, he told the Alsop brothers that he really, really wanted to be President, but he wasn’t sure he would run. He didn’t know if he could raise enough money to win; he didn’t know if he could withstand the grind of the primary calendar; and he was afraid that even if he ran and came out on top, party leaders might still grab the nomination away from him and hand it to someone they liked better.

The Alsops seemed genuinely amazed that a candidate would discuss campaigning as frankly as Kefauver did. “Here there are no doubts, hesitations or equivocations, no complex personal stage settings or dignified pretenses or elaborate political stratagems,” they wrote. Instead, the “solid, amiable, almost artlessly ambitious Tennessean” talked bluntly about the potential obstacles in his path.

One of those obstacles was his family. “The children are growing up, and if I run again, it will just about mean a whole year away from them,” Kefauver said. The Alsops correctly predicted that this would ultimately not keep Kefauver out of the race.

He was right to worry, however. Both his wife Nancy and his children were reportedly opposed to the idea of another Presidential run. Nancy, who campaigned across the country with him and charmed voters everywhere, largely stayed at home in the ’56 campaign. The Kefauvers’ oldest daughter Linda was so upset with his decision to run that she didn’t speak to him for weeks.

If family concerns weren’t enough to keep him out of the race, money was another story.

Again, this was an absolute no-no for candidates to discuss. When Adlai Stevenson was weighing his decision to run in ’56, reporters asked him how he would pay for his campaign. “With money, I hope,” he quipped.

That was how a candidate was supposed to deflect questions about funding. “The dollars to finance the large headquarters, to pay the busy staffs, to meet the bills for the motorcades and the television appearances, are always supposed to materialize as though by magic,” the Alsops wrote, “like the ectoplasm at a spiritualist medium’s séance.”

Kefauver, on the other hand, “talked about the campaign finances with the same solemn, dedicated interest that most people show in discussing the state of their digestion.”

Again, his caution was justified. He’d wound up with over $35,000 in debt from his 1952 campaign, and he admitted to the Alsops that he’d only just finished paying it off, over three years later.

“You need money to make the only kind of campaign I’m able to make, which is a campaign in the primaries,” Kefauver told them.

That reference to “the only kind of campaign I’m able to make” pointed to another hesitation. Kefauver knew that his only hope for winning the nomination was to rack up wins in the primaries, as he’d done four years earlier. But he also knew from experience what an exhausting grind that was.

The Senator glumly confessed to the Alsops that “it’s a man-killing job to try for a nomination by the primary route. There were days, last time, when I just didn’t think I could last out until Chicago.”

And even if he did raise enough cash and ran the primary table, there wars as still a chance for the same bitter ending that happened four years earlier: party leadership might snatch the crown off his head and hand it to some fair-haired boy who’d sat on the sidelines in the primary season. (There’s a bitter irony in the fact that the candidate who basically invented the modern primary campaign did so in an era where you couldn’t win that way.)

In 1952, Stevenson was the fair-haired boy (“egghead” jokes aside). In 1956, that role went to New York Governor Averell Harriman.

Harriman’s campaign was managed by Tammany Hall boss Carmine DeSapio. (Yes, Tammany Hall was still alive in the 1950s.) DeSapio hoped that Kefauver would take Stevenson out in the primaries, allowing Harriman to swan in at the convention and get the nomination. (This plan was no secret; the Alsops mentioned it in their column.)

Kefauver expressed his worry that “someone else will pick up the prize after I’ve half killed myself in the primaries.” But he also acknowledged that there was little, if anything, he could do to keep that from happening. “It’s really a tough problem,” he said with what the Alsops called “a highly uncharacteristic hint of weariness.”

In the end, Kefauver did run for President in ’56, ultimately losing to Stevenson in the primaries. (He correctly predicted to the Alsops that California would be a key primary battleground. He beleived that Wisconsin would be the other key battleground; Stevenson wound up ducking that primary, so Minnesota became the key Midwest primary state.)

You might be wondering if Kefauver had already decided to run at this point, and tricked the Alsops by playing the usual will-he-or-won’t-he game with a different script. But I don’t believe that. Neither did the Alsop brothers, and they had reason to believe him.

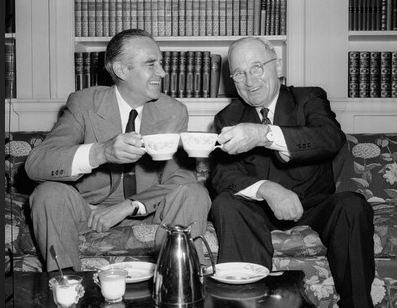

In 1952, when Kefauver was challenging Truman in New Hampshire, he called Stewart Alsop up to his hotel room a couple days before the primary for an off-the-record interview. He confessed to Alsop that he knew he had no chance in New Hampshire, that’s he’d be lucky to win a single delegate and 40% of the vote. Apparently, he was feeling frustrated and wanted to get it off his chest.

Of course, Kefauver wound up stunning Truman (and the Alsops, who predicted a landslide loss) in the primary. But the brothers apparently came away impressed with his sincerity, and when he spoke openly to them in 1955 on his doubts about running, they took him at his word.

For my part, I’m glad for Kefauver that, if he had to lose in ’56, it came in the primaries. As hard as I’m sure it was to swallow another loss to Stevenson, it was an easier burden to bear than winning the primaries only to lose at the convention… again.

As a historian, I’m also glad that he was willing to open up to the Alsop brothers like this. Kefauver generally kept his thoughts to himself; he didn’t keep a diary, and he rarely had heart-to-heart chats with even his closest friends and family. And he seldom talked about the pain of his Presidential campaign losses to anyone.

So it’s helpful to have some of his (relatively) unfiltered thoughts on the subject, and to get a glimpse into the human cost of his towering ambition, his unflagging determination, and the hostility of his party.

Leave a comment