Young people mattered to Estes Kefauver. They were part of his political base, both at home in Tennessee and during his Presidential runs. In return, Kefauver supported them. For instance, he backed a Constitutional amendment to lower the voting age to 18.

In addition, Kefauver celebrated and championed the idealism of youth and their zeal for political and social reform. He took young people seriously; he didn’t condescend to them or treat them as extension of their parents. Instead, he treated them as fellow citizens with their own hopes and issues.

In this respect, young people were a lot like the other “common folks” who strongly supported Kefauver; the Senator made them feel included in political discussions and believe that their opinions mattered, in a way that many politicians of the era did not.

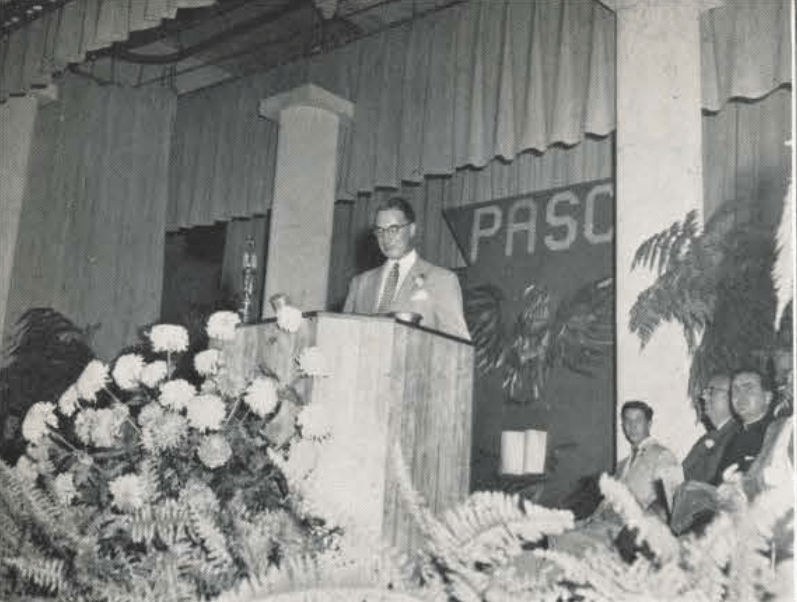

To demonstrate, let’s look at two speeches that Kefauver delivered to young audiences a few months apart. The first was delivered to the Pennsylvania State Association of School Councils Convention in Pittsburgh in October 1953; the second was at a Jaycees (Junior Chamber of Commerce) luncheon in Oklahoma City in May 1954. While both speeches received some local news coverage, they were aimed primary at the youngsters in attendance.

In both speeches, Kefauver called on the young people to lead America and the world toward a future of peace and freedom. He urged them to hold onto their idealism and dissatisfaction with society, but not to cling to outmoded beliefs. He expressed hope that they would be able to solve problems that his own generation had not. He urged them to resist thought policing and protect the right to unpopular opinions.

In short, pretty much everything we associate with the Fifties in the popular imagination – complacency, obedience, unquestioned respect for elders, satisfaction with the status quo, blind adherence to established beliefs – was precisely what Kefauver urged his young audiences to reject.

A Call to Lead… Their Own Way

Lots of politicians talk about how children are the future; it’s become a cliché. But Kefauver didn’t speak in lofty generalities about vague hopes for greater things. He made clear that he was counting on America’s youth to lead the country forward.

“We need, I say, a new dedication like that of those men who built America,” Kefauver told the student council leaders in Pittsburgh. “We need the idealism of youth and we need the participation of youth in governmental affairs. We must get a new faith in ourselves and our democratic way of life.”

Meanwhile, he told the Oklahoma Jaycees that “we have a national duty to see to it that youth is given a chance” to “build a world in which we can use the tools of peaceful living we have already created.” He called on the new generation to develop “fresh concepts of social responsibility and of national purpose.”

Most adults who urge young people to become leaders also encourage them to obey the wisdom of their elders. Not Kefauver.

He assured the student council leaders that “wisdom is not now, and never has been, the monopoly of those of us who have gray hair. Down the ages, in fact, it has been the youth of the world that has carried the banners of progress, that has boldly marched in the vanguard toward a more inspiring and intelligent view of man’s destiny.” Similarly, he told the Jaycees that “what we need is a ‘Young Look,’ a reappraisal of all our problems from the fresh, vigorous, optimistic, determined viewpoint of a youthful nation.”

He saluted the “unquenchable spirit of youthful rebellion,” assuring the youngsters that they were right to be angry and dissatisfied with the state of the world, arguing that throughout history, when “great evils have been corrected… most of the improvements were brought about because youth got mad and did something about it.”

Indeed, Kefauver argued that seeking new ideas and new solutions was deeply embedded in American history.

He reminded the Pennsylvania student leaders that America’s founders “were not satisfied with the status quo. They were explorers not only in the physical sense, but intellectually and spiritually as well. They welcomed new ideas, not being content with stale orthodoxies or a resigned compliance with old customs or outworn opinions… They were sick of the crusty tyrannies handed down from the Middle Ages.”

To the Jaycees, he quoted Abraham Lincoln: “The dogmas of the quiet past are unequal to the stormy present.”

The Threat of War – and McCarthyism

Kefauver believed that the present age had more than its share of storms. “We have lived through one crisis after another in this country for the better part of 40 years,” he said to the Jaycees. “And only the most reckless optimist can foresee anything else for the days immediately ahead.”

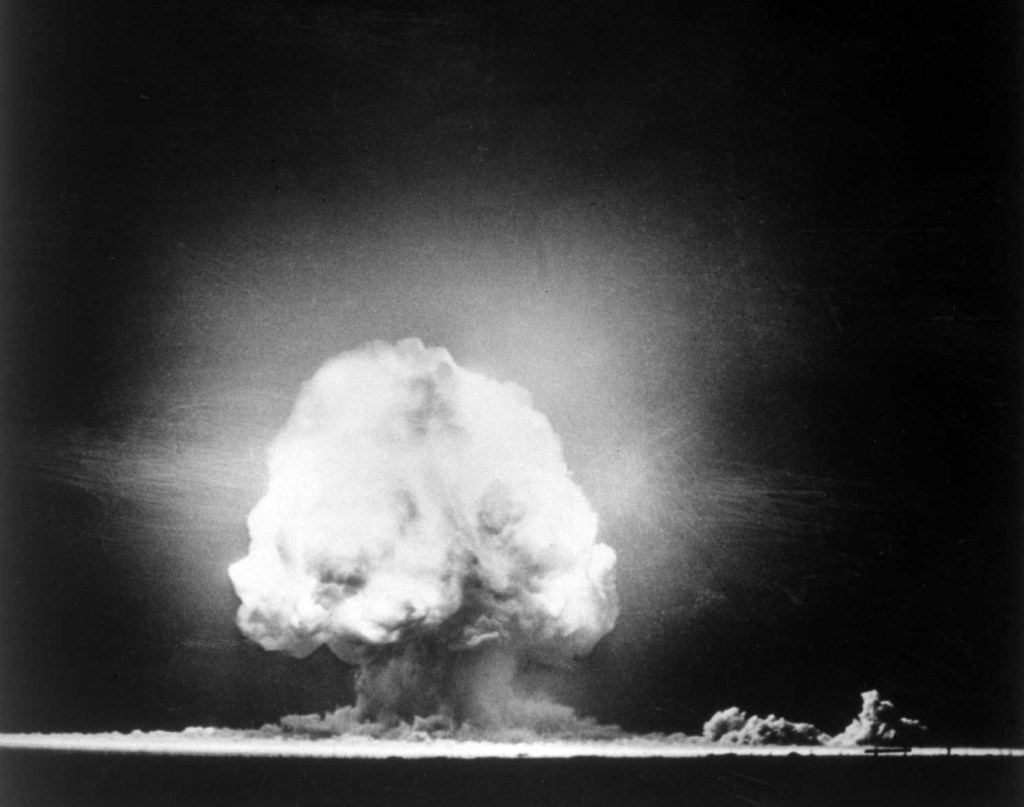

The specter of the Cold War and the threat of nuclear annihilation hung over both speeches. “If the forces of destruction are loosed and make a desert, a vast Sahara, of our green and pleasant world,” Kefauver warned in Pittsburgh, “it will be a clean sweep and leave no oasis for a favored few.” In the same spirit, he reminded the audience in Oklahoma that the search for lasting peace “concerns a world that youth is going to live in, if, indeed, anyone does.”

But the looming possibility of World War III – or nuclear winter – wasn’t the only storm on Kefauver’s horizon. He told the Jaycees how important it was “to keep our minds as well as our bodies free from regimentation.”

In case they were uncertain what that meant, he proceeded to make it crystal clear. (Bear in mind that the Army-McCarthy hearings were going on at the time Kefauver delivered these remarks.)

“[M]any of our citizens have become less and less tolerant to ideas and opinions other than their own,” Kefauver said. “Their intolerance is self-accelerating. The less they agree with other ideas, the more vocal they become. The more vocal they get, the less they seem to think. Soon they are yelling at the top of their voices, without bothering to examine the logic or the substance of their argument.”

Kefauver deplored that “a nation like ours, which owes its birth and its genius to highly unorthodox ideas, should be pushed into a position of hostility to any kind of intellectual deviation. Yet, that is what we face today.” He lamented that “[h]onest, patriotic men have been burned at philosophical stakes while moral savages dance ‘round about in gaudy light before the television cameras.”

He expressed his belief that “our young people, untainted by cynicism and still in possession of their native sense of fair play, resent what this rackety claque are trying to do to our country.” And he called on his audience to stand up to McCarthyism: “We simply cannot afford to have our minds put in uniform and sent goose-stepping down the road to dictatorship.”

Kefauver’s Oklahoma speech occurred the week before the ill-fated vote on the Constitutional amendment lowering the voting age. He reiterated his support for the idea, explaining that it was critical to expand the youth voting population to balance the more conservative views of older voters.

“Ideally, we should have a balance of viewpoints – the vigor and enthusiasm of youth interlaced with the wisdom of age,” he said. “The best and easiest – and I think, the only – way to strike that balance is to lower the voting age to 18 and give youth its chance to be heard in an effective, positive way.”

A Preview of the Sixties?

If Kefauver had given either of these speeches in 1968 (had he lived that long), they would have been considered radical, and viewed as an endorsement of the student demonstrators who so divided the country in that tumultuous year. The fact that these speeches didn’t cause much of a ripple shows how much less of a flash point intergenerational relations were in the 1950s.

But Kefauver’s speeches should highlight a couple of things.

First of all, the Fifties were not as placid and conformist as our mythology likes to imagine. And the protests that erupted across the country in the late Sixties didn’t come out of nowhere. Kefauver wouldn’t have spoken about “the spirit of youthful rebellion” if he wasn’t seeing it in the air.

I don’t believe, had he lived, Kefauver would have embraced campus occupations and all forms of student protest in the late Sixties. He was a strong believer in working within the political and legal system, and generally did not support extra-legal forms of dissent.

But I believe he would have understood why the students were so upset, and he would have embraced their passion for change, if not some of their methods.

One More Thing…

I should also note that one issue was strikingly absent from both speeches: civil rights. This was particularly notable in the Oklahoma Jaycees speech, which occurred less than a week before the Supreme Court issued its ruling in Brown v. Board of Education.

In his Pittsburgh speech, Kefauver called for helping “the peoples of the world… who are in revolt against age-old tyrannies, people who are suffering new tyrannies behind the Iron Curtain, and the hundreds of millions of people who want national freedom and individual liberties,” yet he didn’t mention the millions of black Americans in revolt against the tyranny of Jim Crow at home.

As I’ve mentioned previously, Kefauver’s views on civil rights evolved over time, and he would take bolder stands against segregation after the Brown v. Board decision. But even here, you can start to see the outlines of his evolution.

Kefauver had long worried that white Southerners would resist racial integration if it happened too quickly. But Jim Crow laws were precisely the kind of old and outdated solutions that Kefauver rejected in his speeches. I suspect he recognized this, and he hoped the younger generation would find a way to bring America closer to freedom and equal rights for all.

“The problems we face in our modern world are many and increasingly complex, and we of my generation are not going to solve them all,” Kefauver told the student leaders in Pittsburgh. “Nor will they ever be solved by applying old formulae to them. We need a fresh approach and new departures, and many of those must come from you. We should not be reckless. But still less can we be timid and half-hearted.”

In these words, you can hear him passing the torch to the next generation, expressing hope and confidence that they might be able to solve the problems – like civil rights – that Kefauver’s own generation couldn’t manage.

Leave a reply to Stay on TASK: The Rise of Teens in Politics – Estes Kefauver for President Cancel reply