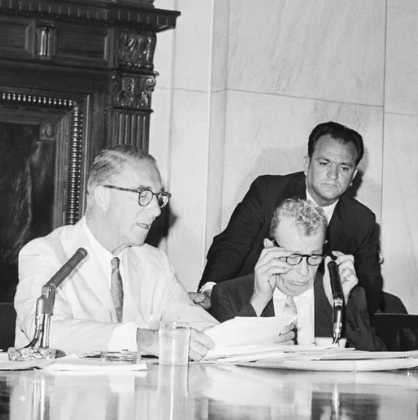

It can be a dangerous undertaking to imagine how a figure from the past would react to today’s political situation. Where would Estes Kefauver fit in today’s political landscape? It’s a tough question to answer.

Some of the issues that he championed – like Atlantic Union and civil defense – are dead today. Nobody’s arguing for a federation of Western democracies, or that we need to build more fallout shelters. On other issues, like civil rights, it’s hard to tell where Kefauver would land. He was considered moderate-to-liberal in his day, but those same views would be considered quite conservative today.

There’s one issue, however, where Kefauver’s views would fit right in today: antitrust and monopoly. If anything, he’d fit in better on those issues today than he did in his time, when he often fought his battles alone.

Today, those, Kefauver’s views would align nicely with a well-known politician: Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts. Warren and her acolytes advance many of the same argument today that Kefauver did in his time.

Because he’s passed into historical obscurity, however, the Warrenites hardly ever cite Kefauver as their spiritual ancestor. I think that’s a shame, because they could learn something from his example.

What’s So Bad About Big Business?

Why are monopolies (or oligopolies) a bad thing? When does it become problematic that a handful of large companies dominate a sector of the economies? How you answer that question has major implications for how you pursue antitrust enforcement.

One theory is that oligopolies allow companies to suppress wages for workers, and that it’s too easy for big companies to become complacent, stifling innovation by smothering newer and nimbler competitors. If that’s your theory, you’d focus on keeping new and innovative companies from being swallowed up by bigger existing firms, and keep an eye out for industries where wages are stagnant.

Another theory is that oligopolies are bad because the dominant firms can charge higher prices, negatively impacting consumers. In that case, you’d be very concerned about industries with high or rising prices, but you wouldn’t worry about big firms as long as they kept their prices reasonable.

Yet another theory is that oligopolies are dangerous because big corporations have outsized influence in our society. According to this theory, if large companies have too much economic power, they will acquire too much political power, thus becoming a threat to dominate the people.

This was the theory that Kefauver believed in. So do Elizabeth Warren and her supporters.

Kefauver’s Fight for Our Rights

One of the central tenets of Kefauver’s political philosophy was a concern about any segment of society becoming too big and powerful. In his mind, the only way to check the power of big business would be through big labor organizations and big government agencies, which would lead America down the road to a future in which the power of the people would be swallowed up by these dominant forces.

As he explained during a 1947 floor speech arguing for what would later become the Celler-Kefauver Act, “It has been my profound conviction that, through this route, monopoly in industry will lead inexorably to some form of collectivism and thus to the disappearance of our economic liberties and political rights.”

Kefauver only grew more concerned as the years went on and more and more industries came to be dominated by a small number of huge firms. In his book In A Few Hands, published after his death, he warned, “Every day in our lives monopoly takes its toll.”

Using examples from his hearings, he showed that dominant firms had the effective ability to set price levels, costing consumers money. “Stealthily [monopoly] reaches down into our pockets and takes a part of our earnings,” he wrote.

He also noted the crushing effect of big corporations on small businesses. “Everyone, at one time or another in his life, has seen economic power throw its weight around,” Kefauver noted. “Any small manufacturer can cite, though he seldom dares to, examples of the exercise of economic power by the corporate giants in his own industry.”

For Kefauver, it all came back to the same problem: the corporations, not the people, were calling the shots – and not just in the business world. “The core of the economic problem facing us today,” he wrote, “is the concentration of power in a few hands… with greater size and concentration, corporations have increasingly moved outside the economic arena into the political realm.”

I’ve Heard That Somewhere Before…

This sort of language would be quite familiar to Warrenites. At a symposium in July 2024, Warren ally Zephyr Teachout laid out a vision of “what antitrust law should be: a tool to promote fair competition, prevent market concentration, and ensure that economic power is distributed broadly rather than concentrated in the hands of a few.”

She added, “It is intuitive that economic power often translates into political influence, allowing these corporations to shape laws, regulations, and policies in their favor.” Kefauver would agree strongly with Teachout’s vision of antitrust.

In a 2023 paper, economist Isabella Weber, another member of this camp, argued that the widespread inflation in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic was an example of “sellers’ inflation,” which was only possible because of “the ability of firms with market power to hike prices.” This sounds quite similar to the concept of “administered prices” that Kefauver discussed in his antitrust hearings.

Senator Warren herself, in a 2017 speech, laid out the problem with a clarity that Kefauver would appreciate:

“Strong, healthy markets are the key to a strong, healthy America. But today, in every corner of our economy, big, powerful corporations are killing off competition… The results are devastating. When those giants kill off competition, prices go up, quality goes down, and jobs are eliminated. But that’s not all. Massive consolidation means the big guys can lock out smaller, newer competitors. It means the big guys can crush innovation… Concentrated market power also translates into concentrated political power – the kind of power that can capture our government.”

Kefauver and Warren even faced similar criticism for their efforts: namely, that they’d failed to get the public interested in their cause.

The year after Kefauver’s death, scholar Richard Hofstadter wrote the famous essay “What Happened to the Antitrust Movement?”, in which he described antitrust as “one of the faded passions of American reform.” He claimed that the field had become too technical and legalistic, and that it had ceased to stir excitement among ordinary Americans.

The economics writer Noah Smith took an even harsher line in a recent essay attacking the Warrenite approach to antitrust. He derided their “anti-corporate approach” as “populism without popularity — an elite intellectual project that was mostly wrong on the actual economics while also failing to spark enthusiasm among voters.” He described antitrust as a “hyper-elite technocratic niche issue” and said that “banging on about the evils of big companies is not going to rouse the American public.”

Reviving a Forgotten Link

Given all the overlaps between their views, it’s a shame that Warren and the modern antitrust backers rarely cite Kefauver. The progressive antitrust movement frequently refers to itself as the “New Brandeis” or “neo-Brandeisian” movement. This is a reference to early 20th-century Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, who crusaded against monopolies and decried what he called “the curse of bigness.”

Justice Brandeis doesn’t exactly loom large in the minds of the average American today. (Granted, neither does Kefauver.) But by focusing on him, I think today’s progressive antitrust crusaders are making a mistake.

Focusing on Brandeis, a contemporary of Teddy Roosevelt, feeds the misconception that the antitrust movement was just a moment in time, at the beginning of the 20th century. Adding Kefauver to the story reminds people that the antitrust movement was in fact a tradition that lasted for decades.

Also, Kefauver’s example would be instructive to the modern antitrust movement. His hearings (not to mention his book) focused heavily on demonstrating how monopolies and oligopolies were hurting average Americans, whether through higher prices, limiting choices available to consumers, or squeezing out small businesses. Unfortunately, the neo-Brandeisians have struggled to make this case today.

I should note that Elizabeth Warren herself is quite good at it. Like Kefauver, she has a gift for speaking plainly and explaining complex issues in ways that the average person can understand.

Unfortunately, many of those in the New Brandeis movement do not. They’re academics who speak like academics, and that contributes to the perception that antitrust is a “hyper-elite technocratic niche issue.” Which is a real shame, because these issues are as important now as they were in Estes Kefauver’s day.

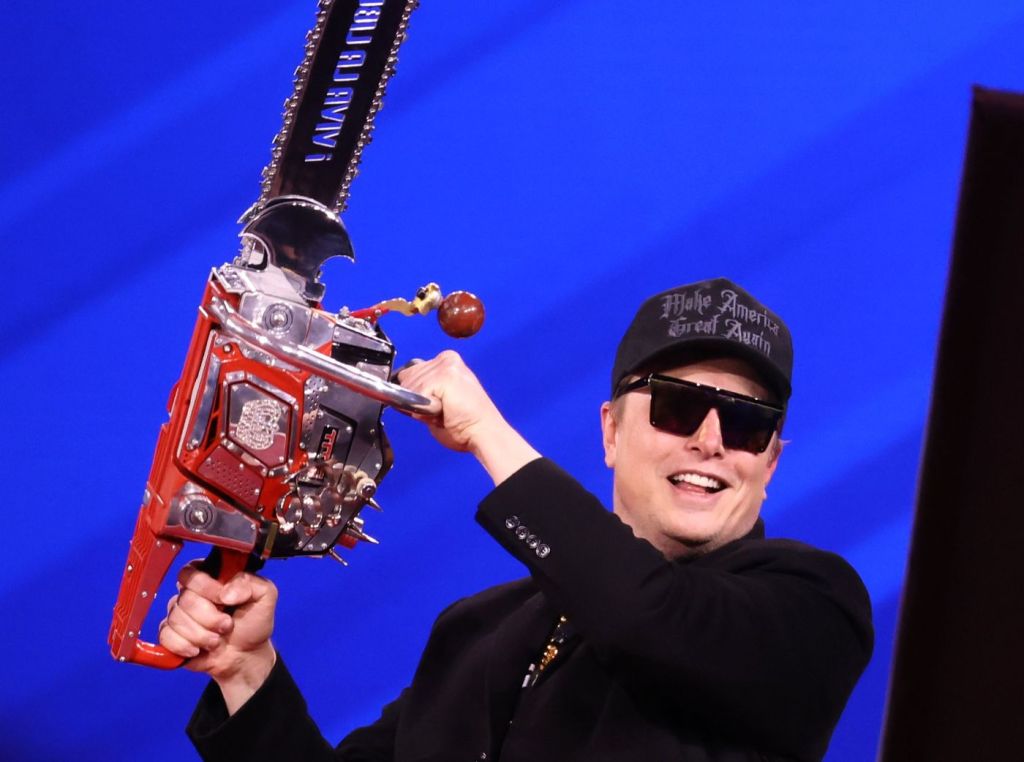

If Kefauver were alive today, I have no doubt that he’d be concerned about the power of companies like Google, Facebook, and Twitter. He’d be appalled by the winner-take-all nature of today’s tech-fueled economy. And he’d be convinced that allowing too much power to concentrate in too few hands is bad for society – and he’d be able to tell the average American why.

Leave a reply to Give Me A Break: The History of A Campaign Slogan – Estes Kefauver for President Cancel reply