When Dwight Eisenhower was elected President in 1952, Democrats found themselves in a deeply unfamiliar position. For the first time since FDR swept into the White House 20 years earlier, the Dems were completely out of power.

Eisenhower’s coattails had been long enough for Republicans to capture both houses of Congress, which Democrats had controlled for most of the last 20 years (apart from a brief blip in 1946). Suddenly, Democrats had to figure out how to operate in the minority, after having spent a generation ruling the roost.

Not only that, they needed to figure out who would be the leader of the party going forward. FDR was gone, and Truman was widely unpopular. Adlai Stevenson had just gotten steamrolled. And many of the party’s leaders in Congress were too old, too conservative, or both. The Democrats desperately needed a new standard-bearer.

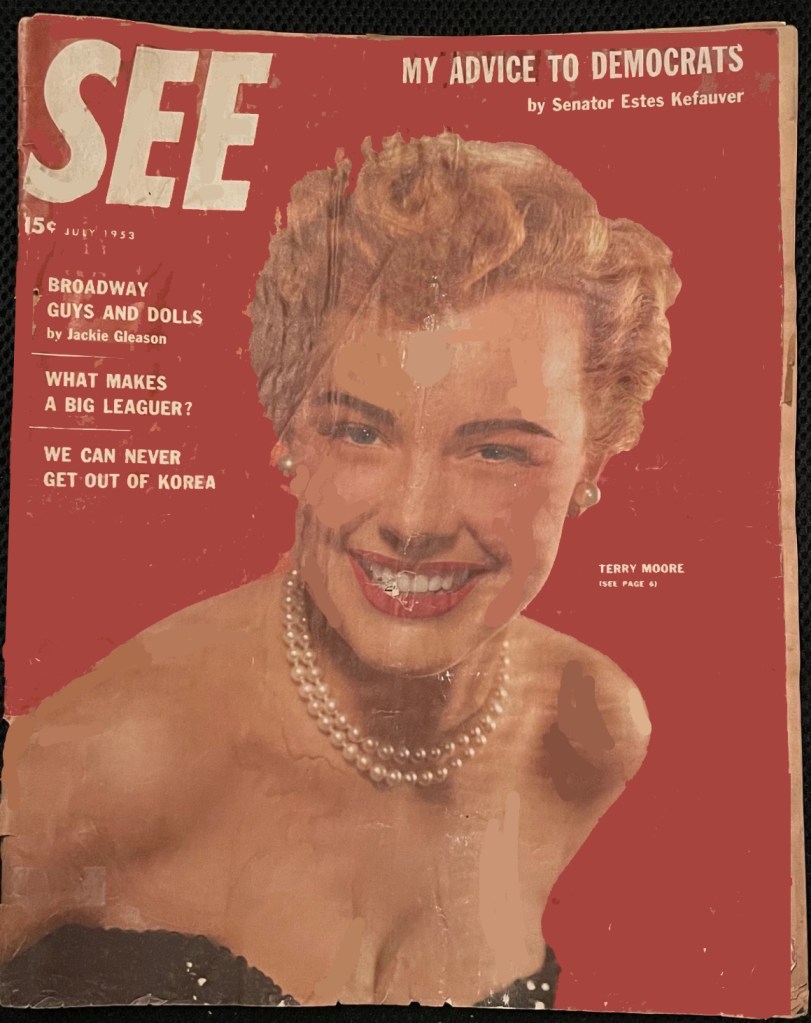

Estes Kefauver wanted to fill that role. And so, in a bid to build on the popular support he’d earned during the organized crime hearings and his Presidential campaign in ’52, he wrote an article in the July 1953 issue of See magazine entitled “My Advice to Democrats.”

See has been completely forgotten today, but it was a large-format general-interest magazine similar to Life or Look, featuring splashy, attention-grabbing photos interspersed with fairly short articles. In this particular issue, wedged between a photo spread of the actress Terry Moore and Jackie Gleason’s predictions regarding the rising stars on Broadway, Kefauver offered his recommendations on how Democrats should conduct themselves in the minority – and what he believed was their path back to the majority.

Overall, the article strikes a high-minded, statesmanlike tone. This was no doubt sincere – Kefauver generally had an idealistic view of politics – but was probably also intended to appeal to Stevenson backers.

This suggests to me that Kefauver thought he’d lost the nomination in 1952 because he was perceived as not being sophisticated or high-minded enough for the Presidency, which wasn’t the case at all. (In fairness, the real reason for his loss – that he’d alienated key power brokers within the party, particularly urban bosses, Southerners, and friends of Harry Truman – was a much harder problem to solve, and certainly not something a magazine article could fix.)

Kefauver recommended that the Democrats adopt the role of “loyal opposition,” offering thoughtful critiques of the new GOP administration rather than blind partisan attacks. “We must be as willing to applaud the majority when we feel it is right as we are to oppose it when it is wrong,” he wrote.

Kefauver cited former GOP Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., who believed the minority should be “the voice of conscience though not of power.” The choice to quote Lodge was interesting for multiple reasons.

First, Lodge was a wealthy aristocrat, a far cry from the working-class voters who made up Kefauver’s base of support. (Again, this seems like a play for the Stevenson crowd, as Adlai was himself a wealthy aristocrat.)

Second, although Lodge led the ultimately successful movement to draft Eisenhower for the GOP nomination, he lost his own Senate seat in the ’52 election to John F. Kennedy, who would ultimately snatch the face-of-the-party role that Kefauver was seeking here.

In a similarly high-minded vein, Kefauver urged the Democrats to campaign responsibly. He drew a contrast with Republicans, who had created a “statement of principles” as a campaign tool for the 1950 midterms that was full of contradictory promises – supporting free trade while also advocating for higher tariffs, for instance, or calling for a balanced budget while also simultaneously urging higher defense and domestic spending and lower taxes.

Kefauver decried this campaign tactic as the “height of irresponsibility.” In essence, he was urging his party not to resort to demagoguery and dishonest promises. (No doubt, he was aware that critics of his 1952 campaign had tagged him as a demagogue.)

Despite the fact that Kefauver was making a play for the sophisticates in this artcle, he couldn’t help slipping in a couple folksy aphorisms, like this one: “We must be watchful – but, please, let’s not become a bunch of old-maid snoopers, forever pumping up trivialities into causes.”

Kefauver’s article wasn’t all about bridge-building and bipartisanship. He called for generational change in party leadership, urging the Democrats to elevate young people and women into positions of power and influence. He also urged the Democrats to embrace the legacy of the New Deal and become an explicitly liberal party, ceding conservative voters to the Republicans. “Ours is the party which believes that the nation will prosper most as the general well-being of the average man is advanced,” he argued.

What did all this translate to in terms of policy? Kefauver argued for continuing FDR’s “philosophy… that government should have a heart.” However, the Senator didn’t sketch out much of an overarching vision, but instead mentioned a grab bag of issues that just so happened to be things he already believed in.

For instance, he urged the Democrats to continue supporting public ownership of power and resource development, citing his beloved TVA as an example of how cheap public power helped spur badly needed economic development in the South. (He pointed out that this development benefitted the entire country, as TVA’s power plants relied on generators, steel, and other industrial products from the North.)

Kefauver also trotted out another pet proposal of his: a recommendation that Cabinet secretaries and agency heads have regularly scheduled presentations before Congress, in which they would report on the status of their department or agency and take questions from both sides of the aisle. Kefauver had shared this idea in his 1947 book A 20th-Century Congress, but he’d been pushing for it almost as long as he’d been in Washington.

Here, he argued that these sessions would ensure that both parties had more information about the workings of the government, but he also believed they would foster a spirit of collaboration between the executive and legislative branches. “There would be a free and open consultation between government administrators and members of Congress,” Kefauver wrote. “They would come to know each other better and share a sense of partnership.”

There were a couple more ideas in the article along these lines, but nothing even vaguely resembling a campaign platform.

My favorite part of the article comes toward the end, when Kefauver extols the virtues of being in a minority. He always had a respect and sympathy for those with unpopular viewpoints, and he suggested that Democrats’ time in the wilderness might offer a chance to heed the better angels of their nature. He cited Jefferson’s Virginia Statute of Religious Freedom, Thomas Paine’s pro-independence pamphlets, and Abraham Lincoln as examples of minority ideas that had a tremendous impact on society.

Kefauver offered a powerful quote from J.B. Gough: “The chosen heroes of this earth have been in a minority. There is not a social, political or religious privilege that you enjoy today that was not bought for you by the blood and tears and patient suffering of the minority. It is the minority that have stood in the van of every moral conflict and achieved all that is noble in the history of the world.”

From another politician, this might seem like an attempt at cope. From Kefauver, though, it rang true.

(If you’re not familiar with Gough – I wasn’t – he was a 19th-century Englishman and recovered alcoholic who gained notoriety as an advocate of the temperance movement in Massachusetts. From there, having proven his oratorical skill, he became a famous lecturer in America and Great Britain.)

Ultimately, the article didn’t achieve what Kefauver hoped it would. The whole “loyal opposition” idea was a tough sell in the heat of the McCarthy Red Scare (although LBJ did maintain a decent working relationship with the Eisenhower White House). Democrats would regain control of Congress the next year and won the White House in 1960. As for Kefauver’s bid to become the Democratic standard-bearer… well, we know how that turned out.

That said, the Democratic Party did – eventually – become an explicitly liberal party and elevate young people and women, as Kefauver hoped they would. As in so many other cases, the party eventually recognized his wisdom – just too late to benefit him.

Leave a reply to Kefauver and the Korea Ammo Hearings, Part 3: Inconclusive Conclusions – Estes Kefauver for President Cancel reply