Declaring “firsts” in history is often tricky. Take, for instance, the following question: What was the first televised presidential debate? Most people think of the famous 1960 clash between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon. Last year, I mentioned the largely-forgotten 1956 primary debate in Miami between Estes Kefauver and Adlai Stevenson, implying that was the real answer. But it turns out that Kefauver was involved in another televised debate in Miami… four years earlier.

I learned about this while I was leafing through an old broadcasting magazine from 1952, looking for something else, when I came across this ad:

First of all, the tagline is a great play on the movie “The Day the Earth Stood Still,” which came out the previous year. Second… how had I never heard of this debate?

It made sense that WTVJ would host such a debate; the Miami TV station was also the site of the 1956 Stevenson-Kefauver faceoff. WTVJ was one of America’s first TV stations, going on air in February 1949. At the time of the Russell-Kefauver tilt in 1952, it was still the only TV station in South Florida. Its schedule was a hodgepodge of locally produced shows and programming from all four existing networks (ABC, NBC, CBS, and DuMont) flown in on kinescopes from New York.

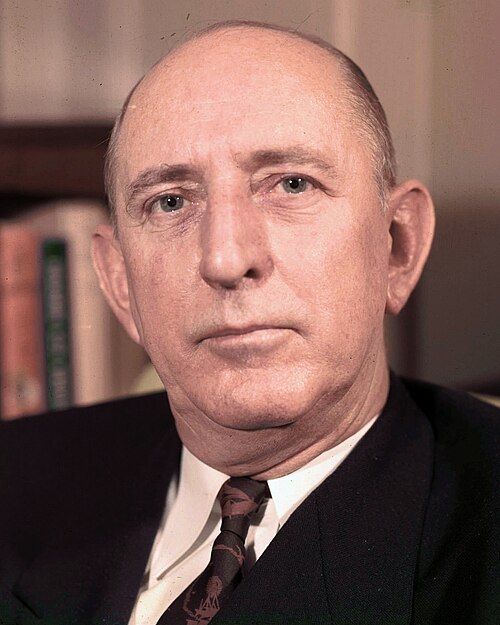

The 1952 Democratic primary in Florida was a source of national interest. It was the only candidate-preference primary being held in the South. (Alabama had a primary in which voters could choose the state’s delegates, but they were all unpledged to a particular candidate.) As such, it was the only primary that Russell – who was running explicitly to represent the interests of the South – formally entered.

Russell and his supporters hoped to use a strong victory in the Florida primary as the basis for negotiating at the convention. It’s doubtful whether Russell’s supporters – or even the Senator himself – thought he had a realistic shot of being nominated. But in the wake of the Dixiecrat walkout at the 1948 convention, Southerners hoped that a strong showing by Russell would give them a delegate bloc large enough to deny the nomination to anyone they didn’t like – and, more importantly, to prevent a strong civil rights plank from being added to the Democratic platform.

For Kefauver, a victory would demonstrate his appeal in all sections of the country. A win in the South – where, despite his own Southern roots, his moderation on civil rights made him deeply suspect – would make it that much harder for party leaders to deny him the nomination. Or so he and his supporters hoped, at least.

For WTVJ, the chance to televise a live faceoff between two Presidential contenders seemed like a ratings bonanza. They bought ads in newspapers and on five different Miami radio stations promoting the debate in the days leading up to it.

And those who tuned in certainly got their money’s worth. The Kefauver-Stevenson debate in 1956 was fairly humdrum; the candidates largely agreed on most issues, and their minor disagreements were generally placid and cordial.

Not so with Kefauver-Russell. Although the debate was nominally directed by WTVJ news director and a panel of questioners, Russell and Kefauver largely made their own rules. The candidates repeatedly talked over each other, challenged each other’s assertions, traded barbs, and tried mightily to get under each other’s skin – and frequently succeeded.

The Associated Press said the debate “developed at times into a bitter and shouting quarrel. Both men showed the strain of their hard campaigns under Florida’s hot sun.” The Tampa Tribune described it as “edged with anger and bitterness” and said “both men carried away scars which will not easily be healed.”

What were they so hot about? Kefauver was upset that all of Florida’s elected officials were backing Russell. He claimed that Russell, the politicians, and the “gangsters and racketeers” had “ganged up on me to try to stop me down here, just as the administration tried to stop me in New Hampshire and Nebraska.” In response, Russell mocked Kefauver for being a crybaby. “You’ve been very effective in this poor-little-Estes attitude, everybody’s picking on him. Poor little fella, can’t hardly get along,” Russell smirked.

Russell, meanwhile, was mad at Kefauver for shirking his Senatorial duties to hit the campaign trail. “I had to haul the water and tote the wood back there in Washington,” he said, because Kefauver, his Armed Services Committee colleague, “wasn’t there. He was off campaigning all over the country, and someone had to do the work.” Kefauver shot back by pointing at the electoral scoreboard: “I don’t see that you’ve made any headway in carrying any states yet, Senator Russell,” he said sardonically.

Russell also attacked Kefauver for making an issue out of the fact that Fuller Warren, Florida’s corrupt governor, had endorsed the Georgia Senator. “You’re trying to hang Fuller Warren around my neck,” Russell snapped. Kefauver replied that Russell had accepted Warren’s endorsement, and “you have to accept the liability that comes with it.”

The most contentious issue, though, was civil rights. In this election, the issue revolved around the prospect of a Fair Employment Practices Commission. During World War II, Franklin Roosevelt – under pressure from black leaders – created the FEPC to investigate cases of employment discrimination against minorities. Congress abolished the FEPC after the war, but activists pushed to make it permanent.

In 1952, liberal Democrats were pushing for a platform plank endorsing a permanent FEPC. In response, Southerners were threatening to walk out of the convention, as they had four years earlier in the Dixiecrat revolt. Russell’s candidacy was backed by those very same Southerners.

Russell’s strategy to win Florida was to paint Kefauver as a traitor to the South on race. Kefauver – who, unlike Russell, was playing to a national audience – tried to finesse the FEPC issue by saying that he personally opposed it, but that if the convention chose to endorse a permanent FEPC, he would abide by the convention’s decision.

Russell hit Kefauver for being two-faced on the issue. Russell said that in the Senate, Kefauver has said the FEPC “was regimentation, that it was of doubtful constitutionality, and that it would not work,” while at the same time telling reporters that if the convention passed an FEPC plank, he would “wholeheartedly support that platform in its entirety.” Either Kefauver had been “greatly misquoted,” Russell concluded, or he was a hypocrite.

Kefauver managed to turn the issue around, however, accusing Russell of being a traitor to the Democratic Party. “I’d say that I’m a Democratic running on the Democratic party,” Kefauver said, and he wouldn’t “pick up my marbles and run out of the party” just because the convention endorsed a permanent FEPC.

Russell tried to push back, claiming that the FEPC “in my mind is completely socialistic” and therefore unworthy of his support. But Kefauver kept pushing Russell on whether he’d quit the party over it, and the Georgian finally exploded. “No, I’m not going to leave the party!” he snapped. “I didn’t leave it in 1948 when they put it in the platform.”

This was true: Russell had not backed the Dixiecrat revolt in 1948. But a lot of his supporters had, and his admission that he wouldn’t quit the party this time deeply disappointed them. His insistence that he would instead “repudiate” the plank felt like weak tea in comparison.

The Shreveport Times, which endorsed the idea of a Southern Revolt against civil rights, acknowledged that Russell has screwed up. “Kefauver backed Russell into a corner and outsmarted him,” said the Times in an editorial, “and Russell still hasn’t wiggled off the spot in the eyes of his followers.”

Kefauver’s stand on FEPC earned him the overwhelming support of Florida’s black and Hispanic population, as well as more liberal Northern transplants in South Florida. Russell’s seeming equivocation, meanwhile, probably depressed turnout among hard-core racists and state’s-rights diehards. Russell won the Florida primary but by far less than expected, with only around 52% of the vote.

So, to return to the question at the top of the post: would it be fair to call this the “first televised presidential debate”? Maybe.

It wasn’t the first nationally televised debate: unlike the 1956 Stevenson-Kefauver forum, this one was only televised in Miami. Since WTVJ wasn’t connected to the national coax cable that transmitted network programming until the fall of ‘52, it couldn’t have been broadcast nationally, at least not live.

The week before this matchup, the League of Women Voters hosted a forum for candidates from both parties as part of their annual convention in Cincinnati. Five candidates, including Kefauver, showed up. Ironically, neither of the candidates who would actually be nominated was there; Dwight Eisenhower (still in Europe commanding NATO) sent a stand-in, while Adlai Stevenson was still insisting he wouldn’t run. (Russell and Robert Taft both declined to participate.)

So was the LWV event the first televised debate? It depends on your definition of “debate.” The LWV provided all the questions in advance, so it was essentially a collection of stump speeches. There was no actual cross-talk or arguments between the candidates.

As the Cincinnati Enquirer’s John Caldwell wrote, “After this if the [LWV] or anyone else announces a television discussion[,] they ought to have just a little argument if only to live up to the advance publicity.” Even the LWV’s own histories of its involvement with presidential debates make no mention of the 1952 forum.

So what can we conclude? Beginning with the 1952 election, there were multiple televised events featuring Presidential candidates. And in 1960, The Kennedy-Nixon faceoff was the first nationally televised face-to-face debate between major-party nominees. If you want to argue that the LWV forum, the Kefauver-Russell tilt, or the 1956 Kefauver-Stevenson event qualifies as the “first televised debate,” I think you can make a case for any of them.

I should point out that, on the same night that Kefauver and Russell debated, Kefauver was involved in another televised debate. Sort of. More on that next week.

Leave a comment