As I mentioned in my recent posts on the Bricker Amendment and the battle over the authority of the Supreme Court, the 1950s brought together a right-wing coalition of anti-Communist zealots, segregationists, and neo-isolationists who feared the creation of a world government. This coalition would rise in power and influence over the coming decades, ultimately helping to elect Ronald Reagan as President.

This coalition sought to repudiate the forces of Communism, integration, and internationalism wherever they saw it. And they didn’t just see it in obvious places like the United Nations and the Warren Court. Today’s story is about the time this coalition took on that notorious hive of left-wing one-worldism… the Girl Scouts.

I’ve Got LeFevre, and the Only Prescription is More Cowbell Less Government

The Girl Scouts had existed for decades in America without being particularly controversial. But the fact that they were a global organization, promoting a message of friendship between nations, made them a target of the far right in the early 1950s.

The first salvos in this battle were fired in 1953, the same year that the battle over the Bricker Amendment heated up. A far-right California group called America Plus complained about the Girl Scouts’ celebration of International Thinking Day on February 22nd, George Washington’s birthday. They argued that celebrating internationalism instead of patriotism on our first president’s birthday was somehow disloyal. (February 22nd was also the birthday of the founders of Scouting, which is why Thinking Day was on that day, but never mind that.)

That same year, a magazine called Southern Conservative attacked the Girl Scouts for positively reviewing books by Langston Hughes and Dorothy Canfield Fisher in their Leader magazine. What was the issue? Joseph McCarthy’s Senate subcommittee had accused both Hughes and Fisher of associating with Communists.

The Girl Scouts’ troubles really began, however, when they stumbled into the crosshairs of a man named Robert LeFevre.

LeFevre was sort of the Rush Limbaugh of his day. He was a radio and television host, and the publisher of a right-wing newsletter. He claimed to have personally seen Jesus, and that his spirit once left his body and ascended to the top of California’s Mount Shasta. He was a dedicated opponent of all forms of government (a philosophy he referred to as “autarchism.” And he was deeply against the United Nations, which he considered a precursor to a tyrannical one-world government.

In early 1954, the Broward County (Florida) Girl Scout Council invited LeFevre to speak at one of their meetings, an offer he accepted. At some point prior to his scheduled talk, however, somebody apparently tipped off the Council to what a wackaloon he was. They then asked LeFevre to keep his talk nonpolitical and avoid any diatribes against the UN. LeFevre indignantly replied that he would not be told what he could and could not talk about, and the Girl Scouts responded by disinviting him.

This turned out to be a mistake. When you attempt to disassociate from a conspiracy theorist, he will naturally assume that you’re part of the conspiracy.

LeFevre promptly began poring through old Girl Scout Handbooks, looking for evidence that the group was part of the sinister one-world cabal. He soon found what he was looking for in the Intermediate Handbook, which had just been revised the previous year, and was now – in LeFevre’s fevered mind – full of socialist world-government propaganda.

He shared this opinion at length in an article called “Even the Girl Scouts,” which ran in his self-published magazine in late March 1954. In it, LeFevre compared the 1953 edition of the Handbook to its 1940 predecessor, and demonstrated how (in his mind, at least) the new version was full of leftist and pro-UN sentiments.

He noted that the Bill of Rights and the Constitution, present in the 1940 version, were nowhere to be found in the new edition. Instead, he claimed, the new Handbook was filled with praise for the UN as part of the suspiciously-named “One World” badge.

He attacked the new Handbook for praising the League of Women Voters (which he described as a left-wing organization) and including “an endorsement of socialized medicine” (apparently because it referred to the existence of the US Public Health Service). He decried the “My Country” badge as “propaganda for government projects, such as public housing, reforestation, and agricultural experiments, all of which have socialist implications.”

Perhaps worst of all, the new Handbook clearly implied that racial prejudice was wrong. The Handbook “encourages members of certain races and countries – specific the Chinese, the Negroes, and the Italians – in thinking that they are looked down upon by Americans, that Americans have been unfair toward them,” LeFevre huffed, decrying the suggestion that “the Girl Scout who does not freely associate with all members of all other races, regardless of their individual merit, is morally deficient.”

LeFevre concluded that based on his research, “I knew that I should hereafter advise all American mothers to discourage their girls from joining that organization, until it stops the U.N. and world government propaganda and becomes what many think it is, a real American organization.”

The Controversy Spills into Congress

LeFevre sent copies of his newsletter to actual newspapers from coast to coast, several of which printed the article and boosted its spread. The article touched a nerve with Chicago businessman B.J. Grigsby, who wrote to the Girl Scouts expressing concern about LeFevre’s accusation. When he found the Scouts’ response unsatisfying, he wrote to his Congressman.

At the beginning of July, Rep. Timothy Sheehan of Illinois read LeFevre’s article into the Congressional Record, repeating the specious charge that none of the Girl Scout badges involved learning the Declaration of Independence or the Bill of Rights. (These were, in fact, requirements for the “My Government” badge.)

Later that month, Rep. Edgar Jonas backed up his Illinois colleague with statements of dissatisfaction from Grigsby.

The Girl Scouts found themselves on the defensive. And the irony of it is that they had already conducted a review of the 1953 Handbook, and were planning updates to several of the passages that set LeFevre off.

The planned revisions to the Handbook, for instance, changed the name of the “One World” badge to “My World,” and deleted references to things like the “World flag” and “World pin” that had aroused suspicion from groups like the Daughters of the American Revolution, who argued that wearing a “World pin” was unpatriotic. They added the full text of the Bill of Rights back in, and added the lyrics of “The Star-Spangled Banner” in the front of the book. As a sop to paranoia around Red China, the revisions removed passages crediting China with bringing the world tea and bamboo, instead crediting tea to India and bamboo to the Philippines.

Unfortunately, the next printing of the Handbook wasn’t scheduled until the fall. So in hopes of quelling the controversy, the Girl Scouts compiled the planned updates as a pamphlet, which they circulated widely. This wound up being a double-edged sword.

On the one hand, it did give the Girl Scouts a talking point to push back on their critics. On the other hand, LeFevre quickly claimed credit for forcing the changes. The Girl Scouts’ insistence that they’d already planned to make these changes before LeFevre ran his column generally fell on deaf ears.

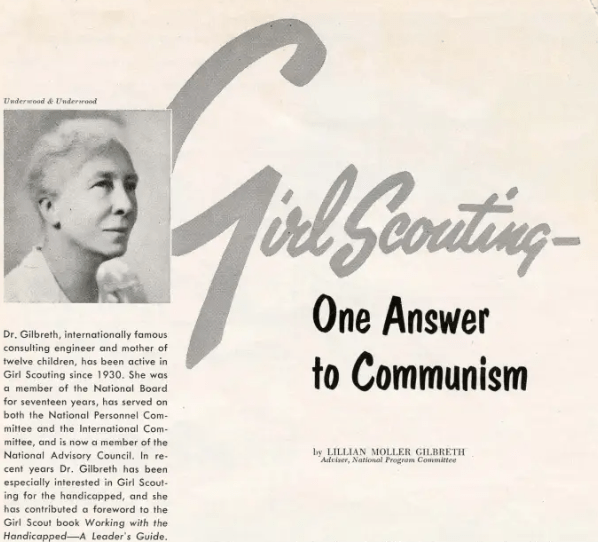

In a more effective pushback, the Girl Scouts convinced Rep. Robert Kean of New Jersey to insert an article entitled “Girl Scouting – One Answer to Communism” into the Congressional Record.

This article, along with pro-Scouting statements by Reps. Charles Brownson of Indiana and Victor Wickersham of Oklahoma, helped turn the tide. By the end of July, even Rep. Sheehan was complimenting Layton and the Girl Scouts for their planned changes to the Handbook.

It looked as though the controversy had died out. But then the American Legion came charging into the fray.

Ready, Fire, Aim! The Legion Gets Involved

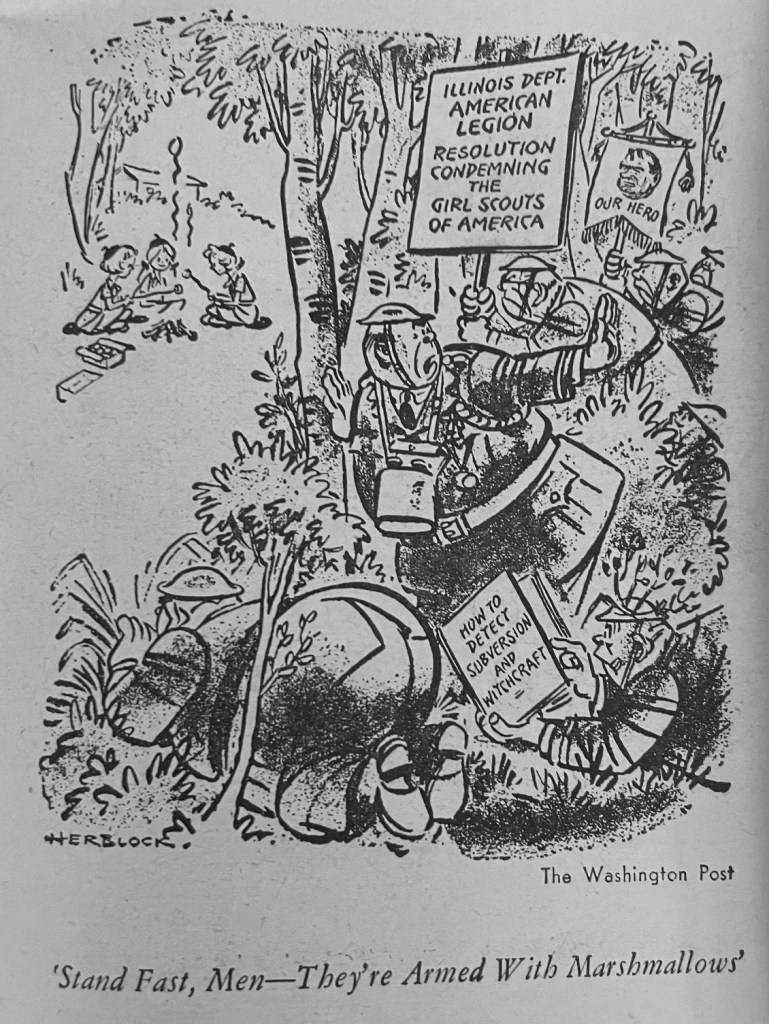

The American Legion could generally be counted on to support the right-wing position of any culture-war battle of the day. When the Illinois department of the Legion held their annual convention in Chicago, it was no surprise that McCarthy – who was widely discredited at this point and was on his way to a formal censure by the Senate – was their featured speaker. And it was equally unsurprising that they’d take it on themselves to wade into the Girl Scout controversy.

Edward Clamage – a Legionnaire who was also headed the Anti-Subversive Committee of Illinois – drew up a resolution calling on the Legion to withdraw “all support of the Girl Scout movement until such time as the responsible directors of the Girl Scouts of the U.S.A. restore the time-honored American, patriotic and historic ideals in teaching to the American youth.”

The resolution claimed that the Girl Scout Handbook gave “United Nations and One-World citizenship precedence over American citizenship,” and that the Scouts recommended “the writings of certain pro-Communist authors,” an apparent reference to Langston Hughes and Dorothy Canfield Fisher.

As the cherry on top of this lunatic sundae, the resolution quoted J. Edgar Hoover and “various investigative committees of the Congress” (guess who) warning that “subversive and un-American influences are attempting to capture the minds of our youth.”

Needless to say, Clamage had never looked at the Girl Scout Handbook or talked to anyone associated with the Girl Scouts; he drew all of his information for this resolution from LeFevre and other far-right commentators. And after a brief but noisy floor debate, the Illinois Legionnaires adopted Clamage’s resolution.

In response, Girl Scout president Layton issued a scathing statement that the organization rejected “the unwarranted and unfair charges with have been made” in the Legion’s resolution. “We have every reason to be proud of our record of forty-two years of devoted service in training girls to be reverent to God and to be loyal, patriotic citizens of the United States,” Layton added.

The general reaction to the Legion’s resolution was… mockery and derision. The Chicago Daily News called the resolution an act of “berserk patriotism,” while Christian Century called it “ridiculous” and admonished the Legionnaires in an article aptly titled, “Time to Grow Up.”

Eleanor Roosevelt also poked fun at the Legion in her “My Day” column. She quoted a Legionnaire who responded to the passing of the resolution by exclaiming, “How screwy can we become!” She added, “If things like this were not so ludicrous, they would be tragic. But fortunately, we can still laugh, and when our patriotic groups become so fearful of communism that they think they find it in those who work for the Girl Scouts, all we can do is laugh.”

Irving Breakstone, newly elected commander of the Illinois Legion, correctly understood what a fiasco the situation had become and tried to put the controversy to bed. He told the Chicago Sun-Times that he deplored “the method used to call attention to the mistakes made by the scouts’ leaders,” and noted that the Scouts had already issued corrections to the Handbook.

Breakstone privately told Layton that the resolution would not make it to the floor of the national American Legion convention in Washington, DC at the end of August. Unfortunately, Breakstone was wrong about that. The Legion’s National Commander, Arthur Connell, promised Layton that she would be given a chance to speak if the resolution did reach the floor. However, he failed to inform her when it did.

At the national convention, the Legion wound up passing a resolution praising the Girl Scouts for their “remedial actions” to clean up the Handbook. However, they also demanded that the Scouts publicly disclose the name of the author who inserted the “un-American influences” in the Handbook in the first place.

A furious Layton blasted the Legion for going back on their word to keep her informed, saying that she had no knowledge of the proceedings “until I read in the paper Wednesday that the resolution had been passed.”

In response, Connell said that any organization “could be infiltrated” by subversive elements, and encouraged the Girl Scouts “to see who in their organization was responsible for the changes in their handbook, that ought to be blamed rather than any individual in the Legion.”

The primary editor of the 1953 Handbook was a woman named Margarite Hall. The Girl Scouts’ director of public relations asked Hall what organizations she was a member of, just to ensure that she had no problematic associations. She responded by listing the First Baptist Church, the American Camping Association, and the Girl Scouts. The PR director’s response: “Good God, what a dull life!”

In the end, the Scouts did not publicly identify Hall and did not fire or discipline her in any way. The Legion wisely decided to quit while they were behind, and the ridiculous controversy finally died.

Postscript: A Silly Debate With Serious Undertones

So, what can we learn from this absurdity? First of all, it’s clear that the right-wing information ecosystem, which we tend to treat as a modern creation of Fox News and social media, dates back decades farther than we typically admit.

Obviously, the spread of LeFevre’s article was helped by the fact that it was published in mainstream newspapers. But look at the Legion’s resolution. It was clearly based in part on LeFevre’s article, but LeFevre didn’t mention Langston Hughes or Dorothy Canfield Fisher at all. Therefore, Clamage must have also read Southern Conservative or some other source that referenced that part of the story. The concept of people becoming radicalized by a steady diet of far-right newsletters, radio, and TV shows is not a purely modern phenomenon. The robust membership of the John Birch Society didn’t come out of nowhere.

Second, the incident underscores the degree that the fears behind the Bricker Amendment were real. Today, it’s difficult to imagine anyone being genuinely afraid of the United Nations; while a well-intentioned concept, it has no teeth. But in the years after World War II, it’s clear that people really believed that some sort of world government might be imminent. (See Kefauver’s proposal for Atlantic Union.)

The first-hand knowledge of the horrors of war – and the fears of how much worse it could get when nuclear weapons were involved – forced us to consider seemingly radical solutions. As crazy as Bricker and his cohorts seem to us today, they weren’t entirely boxing at shadows. (Instead, we got Pax Americana, which provided many of the benefits of Atlantic Union without the loss of national sovereignty. Whether or not this was a good tradeoff is another question.)

I can’t help but regret that Stephen Young was not in Congress at the time. I’m sure he would have had something appropriate to say to LeFevre, the Legion, and the others engaged in this very silly controversy.

Finally, I’d point out that the time period of this controversy – the summer of 1954 – overlapped with Kefauver’s Senate primary campaign against Pat Sutton. Since Sutton was in the House in the time, I’m sure he was familiar with it.

And yet, despite the fact that Sutton threw out basically every charge he could dream up to accuse Kefauver of being a Commie-loving one-worlder, he never (as far as I can find) commented on the Girl Scout controversy. Perhaps it shows that even a candidate as foolhardy as Sutton realized that you didn’t make friends by picking on the Girl Scouts.

Leave a reply to Reds vs. Rights: The Great Cold War Debate – Estes Kefauver for President Cancel reply