One of the issues Estes Kefauver touted in his final Senate campaign in 1960 was his support for a federal Department of Science. “If war should come tomorrow,” he stated in a campaign brochure, “it will have been won on the scientific laboratories of the world today.”

Obviously, we don’t have a Department of Science today, so the proposal was never adopted. But should it have been? And why was it suggested in the first place?

As it turns out, this was yet another ripple of the Cold War, which dominated so much of the political discussion in America in the mid-20th century. Despite powerful support for the Department of Science proposal, its failure could be attributed to a couple common factor: a disagreement over details, and an inability to maintain action after an immediate crisis.

Soviet Sputnik Shocks Scientists

The idea of a Cabinet-level department focused on science was not new; proposals date back to the early 19th century. However, the idea took on new urgency after World War II and the development of the atomic bomb.

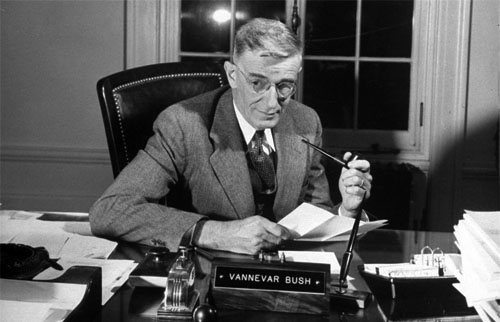

In 1945, Dr. Vannevar Bush, head of the wartime Office of Scientific Research and Development, raised the issue in a report entitled Science: The Endless Frontier:

We have no national policy for science… There is no body within the government charged with formulating or executing national science policy. There are no standing committees of the Congress devoted to this important subject. Science has been in the wings. It should be brought to the center of the stage – for in it lies much of our hope for the future.

The following year, Rep. Clare Boothe Luce of Connecticut introduced a bill to create a Department of Science. However, given the pressing issues facing the country in after the war – such as labor strikes and price hikes – the proposal was buried in committee.

A decade later, however, the Soviet launch of the Sputnik 1 satellite rattled America badly. Sputnik was the first artificial satellite successfully launched into orbit, and the US had no idea it was coming.

The successful launch triggered a panic. The Soviet space program was more advanced than we had realized, and America felt itself falling behind. The US was not only at risk of losing the space race, but the Cold War more generally.

Kefauver captured the dramatic stakes at hand when presenting his proposal to the Senate Government Operations Subcommittee. “If we win this race with Russia, we stay free and help millions of our fellow men in free nationals all over the world to stay free,” Kefauver said. “If we lose, the price could easily be slavery and fear for generations.”

This rhetoric sounds rather overheated today, but it didn’t at the time. Whoever established control of outer space, many felt, would determine the fate of the world.

Getting Serious About Science

In response to the Sputnik crisis, American leaders called for a greater investment in and focus on science and engineering. Within a year, they had created NASA to oversee America’s space program and the Advanced Research Projects Agency (now DARPA) to develop cutting-edge military technology. The House and Senate stood up new committees focused on science and technology. Congress also passed the National Defense Education Act of 1958 (sponsored by Kefauver), which provided student loans and other funding to encourage the study of science, engineering, and math.

The capstone of these efforts was the proposal to create a Cabinet-level Department of Science. Scientific research programs were scattered across many cabinet departments, and supporters believed that bringing them under one umbrella would facilitate coordination and raise the overall focus on science within the federal government. Advocates also hoped that the Department would establish priorities and advocate for greater federal funding of scientific research.

Two major Department of Science proposals were introduced in the Senate in 1958. The first, sponsored by Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota and John McClellan of Arkansas, proposed establishing a Department of Science and Technology. Their bill involved a sweeping reorganization of civilian scientific agencies, bringing the Atomic Energy Commission, the National Science Foundation, NASA, the National Bureau of Standards, and the Patent Office under the jurisdiction of the new department.

The other proposal, sponsored by Kefauver, was more modest. It would have placed the NSF and the AEC under the Department of Science, as well as transferring Defense Department programs focused on outer space research. Kefauver’s Department of Science would have jurisdiction over development of non-military rockets and missiles, as well as all research on outer space. (His bill was formulated prior to the official creation of NASA.)

Kefauver believed a narrower focus on rockets and outer space was the best response to the Soviet challenge. He believed that if these programs remained under the Defense Department, they would always take a back seat to weapons development, particularly since Defense Secretary Charles Wilson felt that weapons were, in Kefauver’s words, “the only thing the Pentagon was supposed to deal with.”

In a Senate floor speech on his proposal in January 1959, Kefauver argued that “we shall never go ahead as we should in… matters relating to science until we have some overall coordination of our efforts; and this bill is for that purpose.”

The Senate Government Operations Subcommittee, chaired by Humphrey, considered both Department of Science proposals in 1958, but failed to advance a bill out of the subcommittee.

Swing and a Miss in ‘59

Both Kefauver and Humphrey reintroduced their bills for the 86th Congress in 1959, and it was widely believed that the proposal would move forward this time. One knowledgeable source made a prediction in Missiles and Rockets magazine that April. “It’s coming,” the source said. “It might not be this year, but you can bet your life on it: The United States will have a Department of Science before too long.”

The proposal’s backers considered it an auspicious sign when Sen. Ralph Yarborough of Texas signed on as a cosponsor of Humphrey’s proposal. Yarborough was closely allied with Lyndon Johnson, and his move was taken as a sign that the idea had LBJ’s blessing.

Humphrey’s subcommittee held hearings on both proposals in April and May of 1959. They received testimony from scientific luminaries of the era, including the heads of the American Chemical Society, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and the National Society of Professional Engineers, as well as the research directors of IBM and Bell Labs.

They also heard from Commerce Secretary (and former AEC chair) Lewis Strauss, as well as the heads of several of the agencies who were proposed to move under the Department of Science. Most of those testifying saw the value in greater coordination of federal scientific efforts.

That said, several objections to the proposal emerged. Representatives of the affected departments and agencies largely opposed the concept, for fear of losing power and prestige (in the case of departments losing functions) or independence (in the case of stand-alone agencies slated to under the department). These same objections were raised to Kefauver’s Department of Consumers proposal a couple years later.

The Eisenhower administration seems to have been opposed to the idea generally. Secretary Strauss, apparently conveying the administration line, argued that it would be inappropriate to confine science to a single department, and that doing so would risk isolating science from other areas of public affairs.

Strauss pointed out that most large corporations had R&D organizations within each division, rather than a single one for the whole corporation. “This entails some overlapping,” he said. “It entails some duplication. But they regard it as a small price to pay for the fact that each of their divisions is alive to the scientific possibilities of growth and new ideas.”

In March 1959, Eisenhower established a federal Council of Science and Technology to encourage coordination between the heads of scientific agencies within the government. It was viewed by critics as an attempt to ward off a Department of Science; indeed, many witnesses who opposed the creation of a department argued for giving the Council a chance to prove its effectiveness.

(This idea sat poorly with Humphrey, who grumbled that the Council’s reports weren’t shared with Congress and its director could not testify on the Hill. “We see the reports as they are filtered, strained, restrained, and constrained,” he said. “We finally get that housebroken, tamed report so that we never really get the gory details. We are treated as if somehow or another, we have an emotional instability and couldn’t take this shock treatment.”)

Meanwhile, the scientific community had its own concerns. They feared that centralizing scientific functions in a single department would lead to politicians dictating what and how they could research. They also worried about research funding; either they feared the Department of Science would get short shrift in appropriations battles, or they feared that the department would prioritize flashier and more visible applied research (like the development of rockets) over less exciting but necessary basic research.

Even those who supported creating a Department of Science disagreed widely over what functions the department should perform. In 1958, distinguished physicist Lloyd Berkner suggested a Department of Science and Technology that would be focused on physical sciences such as oceanography, meteorology, climatology, and so on. This was markedly different than either Humphrey’s or Kefauver’s proposal, and led to further confusion and disagreement.

Attempting to capitalize on the debate, Kefauver pitched his proposal as a short-term solution to address the immediate need. “We need action and we need it fast,” Kefauver said. “Duplication of effort is wasting our resources and retarding our country in this very fast and dangerous race.” He noted that while Humphrey’s bill was “more comprehensive, [if] it is going to be a big fuss about whether all of the agencies that you have set forth to be transferred in your bill would delay at least making a start, that it would be better to start with the obvious ones.” Unfortunately, there was no more agreement on moving the agencies in Kefauver’s proposal than on any of the others.

Given the lack of agreement on a path forward, Humphrey’s subcommittee created a new bill to charter a commission to study whether a Department of Science made sense, and if so, what agencies and programs should move under its jurisdiction. It was a punt, but under the circumstances, it was a sensible one.

Even as the subcommittee reached this compromise, Humphrey fretted that momentum was slipping away. “[W]e have now had about 2 years, I think, since Sputnik,” he commented after Kefauver’s testimony. “We can see what is happening to the American public by the less than avid interest in this subject matter as indicated by these hearings. When we held hearings on the science bill a year ago, there were many more people than there are now attending and much more controversy, much more interest, but we are sort of coasting again.”

Referring to the Cold War, Humphrey noted, “If we win it will be really with the arm of the Lord around us, because we surely aren’t working at it. There is just nothing being done. All they can think of doing is just building another bomb.”

Humphrey’s words proved all too prophetic.

The Proposal Never Dies… It Just Fades Away

In the end, the 86th Congress did not vote to create a Department of Science, nor even to create a commission to study it. When Kefauver died in 1963, Congress was still debating whether to create a study commission. They never did.

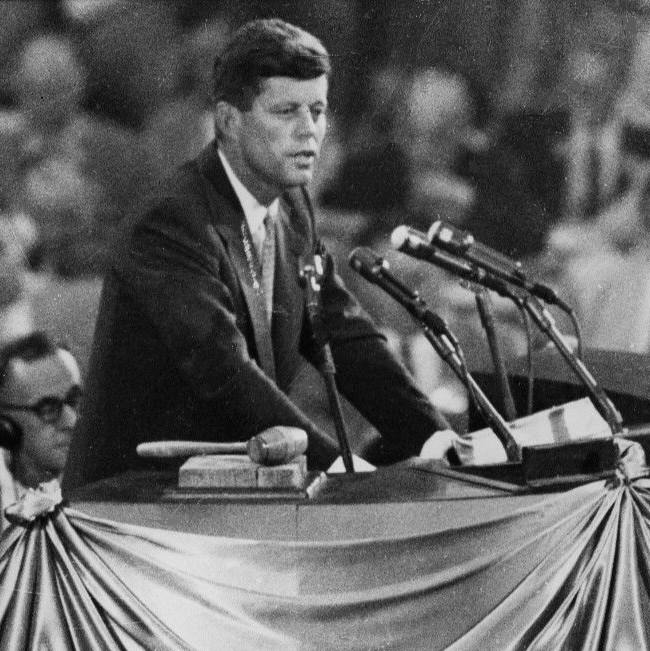

In 1962, President Kennedy created an Office of Science and Technology to serve essentially the same function that Eisenhower’s Council of Science and Technology had. Even though Jerome Wiesner, the office’s first director, said that “the OST is neither a substitute for or in competition with a Federal Department of Science,” it was used by critics to argue that there was no need for a Department of Science.

President Nixon abolished the OST, along with the President’s Science Advisory Council, in 1973. In 1976, President Ford replaced it with the Office of Science and Technology Policy, which exists to this day.

Consideration of a Department of Science came and went in the ensuing decades, but it never got past the idea stage. As recently as 2021, an article in Scientific American called for creating a federal Department of Science and Technology. (It made no mention of the previous attempts to do so.)

In the end, America didn’t need a Department of Science to win the space race. We landed a man on the moon in 1969, something the Soviets never managed. And outer space never did emerge as a Cold War battlefront; neither the American nor the Soviets ever took control of space or deployed weapons there.

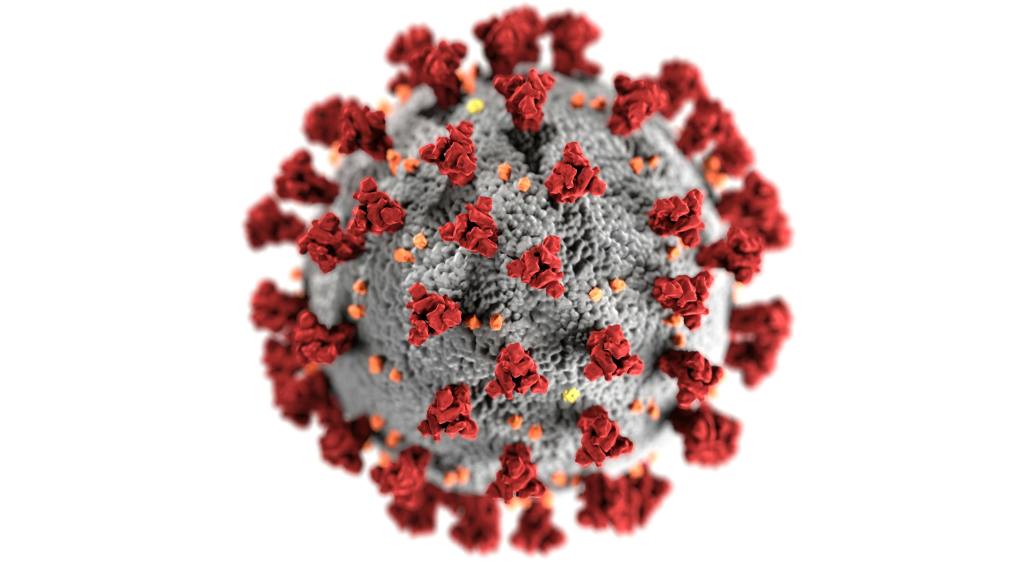

That said, I believe a federal Department of Science and Technology would have been a good idea. America’s science policy is clearly hampered by the fact that scientific agencies are scattered across multiple department, and our response to the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated our shortcomings in coordinating a response to a major scientific challenge.

It’s a shame that we missed the opportunity that the Sputnik crisis presented. For a moment, America’s attention was riveted on science and engineering, and we had the collective will to do something. But instead, we got bogged down in a debate over details, and the public moved on before we could do something.

As we’ve seen, public panics can be a double-edged sword. If Congress moves too quickly in response to a panic, we can wind up with ill-considered laws like the Jencks Act (or even worse ideas like the Bricker Amendment or the Court–curb bills of the late ‘50s). But if Congress moves too slowly and the panic dissipates, we can miss out on worthwhile ideas, like civil defense or the Department of Science.

And given that most of our debates around government today seem to revolve around whether we should burn it all down to the ground, I miss the days when we had voices like Kefauver and Humphrey, who envisioned ways that our government could better serve the people and tried – however successfully – to make that happen.

Leave a reply to Kefauver’s Unconventional Thoughts on Conventions – Estes Kefauver for President Cancel reply