Last week, I began telling the story of the forgotten conservative revolt against the Warren Court. I mentioned how a string of decisions on school integration and the civil liberties of Communists activated a coalition of Southern Democrats and reactionary Republicans, who proposed several bills aimed at curbing the Court. Two bills – the Smith bill in the House and the Jenner bill in the Senate – stood out as the biggest threats to the Court’s power. (For the details of those bills, see last week’s post.)

Today, I’ll conclude the story, explaining a key amendment that gave Jenner’s bill new life – and how LBJ finally defused both bombs on the floor of the Senate.

The Butler Did It: Sweeping Amendments Keep Jenner’s Hopes Alive

Despite widespread opposition, Jenner’s bill returned to the Judiciary Committee in March 1958 essentially unchanged from its original form. It appeared destined to die in committee until a sympathetic colleague, Sen. John Marshall Butler of Maryland, rode to the rescue with a series of amendments.

Butler’s amendments preserved the spirit of Jenner’s bill while substantially changing its form. It preserved the ban on Supreme Court review of cases involving admissions to state bars. Otherwise, as the New York Times explained, “instead of trying to abridge the court’s review power, it aims chiefly to change the effect of particular decisions.”

Butler’s amendments effectively invalidated several Warren Court rulings:

- Invalidating the Court’s holding in Watkins v. US, Butler’s amendment stated that Congressional committees would determine for themselves whether a question was pertinent to their investigation. The witness would have to challenge the pertinence of a given question within the hearing itself, and the committee’s decision would be final.

- Invalidating the Court’s holding in Cole v. Young, Butler’s amendment would make it legal to fire any government employee for suspected Communist associations, not just those in sensitive national-security positions.

- Invalidating the Court’s holding in US v. Young, Butler’s amendment would revise the Smith Act to outlaw advocacy of Communist doctrine in the abstract, not just specific advocacy of dangerous or illegal actions. It would also broaden the prohibition against illegal “organization” on behalf of subversive groups.

- Invalidating the Court’s holding in Pennsylvania v. Nelson, Butler’s amendment stated that federal anti-subversion laws did not preempt state anti-subversion laws. In addition, the amendment stated that no federal laws preempted state laws on the same subject.

The last portion of the amendment led the Justice Department to oppose Butler’s amendment; as with Smith’s bill, they felt that broad nullification of federal preemption would create problems in areas like interstate commerce regulation.

Nonetheless, Butler’s amendment looked good enough to the Judiciary Committee, and they were ready to adopt it. However, Thomas Hennings blocked an immediate vote on Butler’s version of the bill, instead calling for hearings to be held.

“In my opinion, each of the disparate provisions of this amendment should be introduced as a separate bill and considered on its own merits,” Hennings wrote in a memo to the committee. “Legislation should not be considered by bringing several unrelated provisions into an amalgamation and by rushing it through. Such action usually will bring about only undesirable results.”

In a radio address to his Tennessee constituents, Kefauver explained his opposition to both Jenner’s bill and Butler’s amended version, calling it “a very dangerous piece of legislation which seeks to undo 150 years of judicial history with a sweep of the pen.”

He pointed out that “we made a decision in this country a long, long time ago… that we would have three coordinate branches of government – the executive, the legislative, and the judicial – each acting as a check on the other. I will be no party to the destruction, or serious crippling, of any one of the three.”

After walking through his objections to each of the provisions in both Jenner’s and Butler’s versions of the bill, Kefauver concluded by calling it an assault on fundamental American freedoms. “When you begin to impinge on liberty a little bit, you sometimes find you have stepped on it altogether,” he said. “We’ve grown to be a great country by speaking and acting freely. The quick and easy way to become second-rate is to limit our basic freedoms of thought, of speech, of the press, of religion, and of action.”

In spite of these eloquent objections, the Judiciary Committee voted 10-5 in favor of Butler’s version of the bill.

Those on the losing side – including Hennings, Kefauver, Alexander Wiley of Wisconsin, and John Carroll of Colorado – filed a scathing minority report, saying the bill reflected a “kill the umpire” philosophy. In response to Jenner’s claim that Americans were overwhelmingly opposed to the Court’s decisions, the minority report said that “[t]he majority of the people undoubtedly do not want the Supreme Court reduced to the whipping boy of the Congress. This is the intended purpose of this intimidating and coercing proposal.”

Nonetheless, the bill would go before the full Senate, where it stood a good chance of passage. At the same time, Sen. John McClellan of Arkansas filed a proposal to substitute the language of Smith’s House bill for another bill already on the Senate floor – bypassing the Judiciary Committee.

All eyes were now on the Senate Majority Leader, Lyndon Johnson. LBJ opposed both the Jenner-Butler bill and the Smith bill, but he knew that a lot of Senators – including many in his own party – were in favor. Keeping the bills from becoming law would require his best legislative wizardry.

Help Us, LBJ, You’re Our Only Hope

Johnson’s first move was to push the bills until the last week of the session, knowing that this would limit the time spent considering them.

The bills finally came up for debate on August 20, the second-to-last day of the session. Speaking in favor of his and Butler’s bill, Jenner claimed “a crisis in law enforcement, a crisis in dealing with the Communist conspiracy; but, above all… a constitutional crisis,” to which his bill was the answer. He claimed that the bill was just applying “one of the check-and-balance provisions of the Constitution” to restrain “a runaway Supreme Court.”

Hennings, leading the opposition, called the Jenner-Butler bill “the first swing of the ax in chipping away the whole foundation of our independent judiciary.” He blasted the bill as “a legislative decree to the Supreme Court that it should render decisions which are politically popular or it will lose its power to review such cases.”

Hennings then made a motion to table the bill. Thanks to LBJ’s arm-twisting, Hennings’ motion passed, 49-41.

-Hennings after the vote, probably

The Senate then took up McClellan’s proposal to bring the Smith House bill to the Senate floor. Here, the bill’s opponents focused on the fact that it had not gone before the Senate Judiciary Committee.

“If ever there was a piece of legislation which should have some hearings and consideration it is this,” Kefauver said. “The people have to know under what law they are supposed to operate.”

Hennings warned that if the bill passed, “there will be chaos. There will be litigation; indeed, a great compounding of litigation. We will find ourselves in an endless labyrinth of uncertainty and indecision.”

Hennings moved to table McClellan’s motion on the Smith bill. Johnson was confident that he had the necessary votes to table. But then liberal Senator Paul Douglas of Illinois– without giving advance notice to LBJ or even his fellow liberals – proposed an amendment expressing support for the Supreme Court’s recent decisions on integration.

“Do we stand on the side of Governor Faubus,” said Douglas, “or do we stand on the side of the Supreme Court?”

Douglas’ well-intentioned action blew up LBJ’s careful legislative calculations, antagonizing Southern Democrats (some of whom Johnson had persuaded to oppose the Smith bill). Once the furor died down and Hennings’ motion to table came to a vote, it lost 46-39.

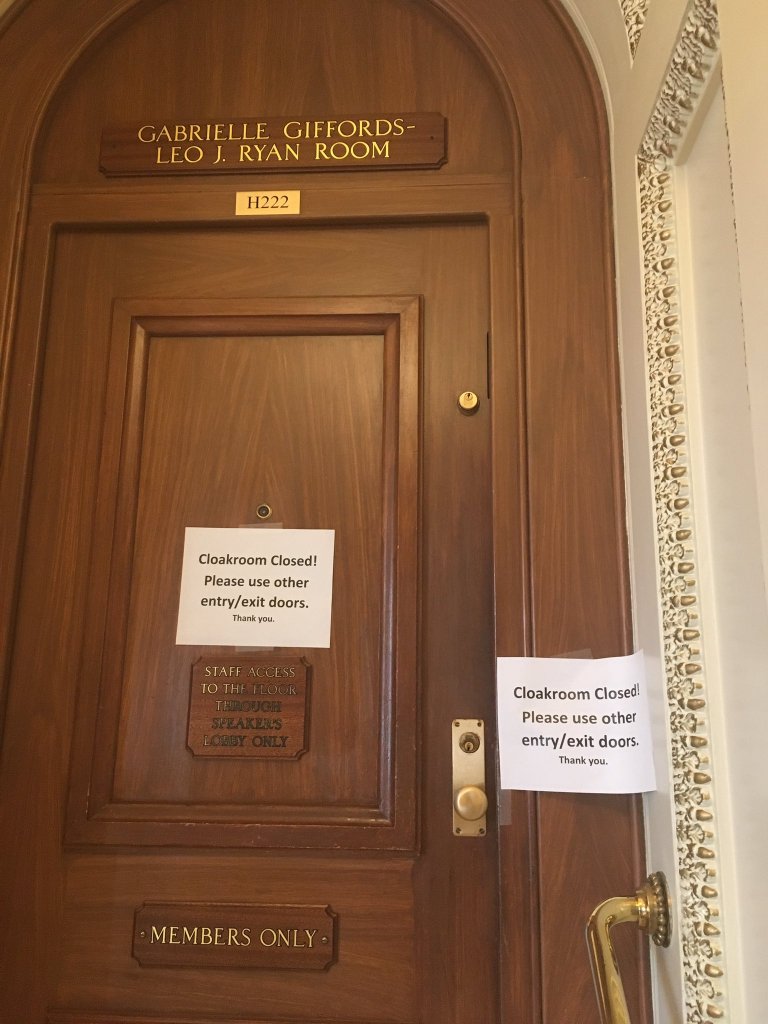

A flustered LBJ recessed until noon the next day. During the recess, he pulled out all the stops. He persuaded Florida’s George Smathers, who planned to vote for the Smith bill, to pair with Oklahoma’s Mike Monroney, who was absent. (In vote “pairing,” Senators on opposite sides of an issue get to express their positions, but they don’t actually vote.) He also persuaded Oklahoma’s Bob Kerr and Delaware’s Albert Freer, two more pro-Smith votes, to remain in the Senate cloakroom and miss the vote.

“In deference to a friend who had a tough job on his hands and who had worked miracles at keeping Democratic harmony during a long and grueling session,” syndicated columnist Drew Pearson wrote, “they did not vote.”

In the end, after all of Johnson’s cajoling and dealing, the Senate voted to recommit the Smith bill (thereby killing it) by a single vote, 41-40. Kefauver joined Johnson and Ralph Yarborough of Texas as the only Southerners to vote to recommit. (Even Kefauver’s Tennessee colleague Albert Gore voted for the Smith bill.)

The Memphis Press-Scimitar hailed Kefauver’s courage. “One thing sure: Kefauver’s vote was one he cast after deciding to do what he thought was right, rather than what would be popular,” the paper declared in an editorial.

But the biggest story was Johnson and his masterful work to achieve his desired outcome. “Like every recent session of Congress, the one just ended has been dominated by the figure of Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas,” wrote Anthony Lewis of the New York Times, adding that Johnson “has never demonstrated greater mastery of the legislative process than in his handling” of the Court-curb bills.

LBJ gave his Southern colleagues a chance to register their unhappiness with the Court (and demonstrate said unhappiness to their constituents) while ensuring that the Court’s authority remained intact.

The Crisis Ends with a Double Retreat

The animosity between Congress and the Court receded significantly after 1958. Several prominent Court critics (including Jenner) retired or were defeated in the midterm elections. The midterms also ushered in a class of pro-Court Democrats, including Eugene McCarthy, Ed Muskie, Philip Hart, Thomas Dodd, and Stephen Young. The shift ensured that anti-Court legislation would be buried in the Senate.

The Court also pulled back on its expansive conception of civil liberties. They held firm on civil rights for black Americans (with decisions like Cooper v. Aaron, in which they ruled that the city of Little Rock could not delay its planned timeline for integration just because of the governor’s and state legislature’s intransigence), but in the areas of national security and Communism, the Court’s rulings became a bit less sweeping.

For instance, in 1959’s Uphaus v. Wyman, the Court ruled that Pennsylvania v. Nelson did not prohibit states from having anti-subversion laws at the state level, or prosecuting people for subversive activities against state governments. (Ironically, Kefauver had proposed this approach as an amendment to an anti-Court bill in the Senate, the bill that McClellan replaced with the Smith House bill.)

The combination of the Senate’s leftward turn in the 1958 midterms and the Court’s quiet pullback was enough to quell the revolution in Congress. Thereafter, negative opinions about the Warren Court were largely confined to the usual grumbling.

Postscript: A Preview of Future Hostilities

Perhaps because of the fact that most of the proposed anti-Court bills failed, the conservative revolt against the Warren Court was largely forgotten.

This is a shame, because this episode – like the equally forgotten battle over the Bricker Amendment – was an early preview of the conservative coalition that would rise in the 1970s and 1980s. The combination of Southern state’s-rights supporters, national security hawks, and anti-Communist zealots that opposed the Warren Court was (with a few additions) the same combination that would elect Ronald Reagan in 1980.

In addition, this showdown over the Court’s authority might have shownboth sides that they had gone a bit too far. Anthony Lewis of the Times decried the actions of Jenner and the conservatives as “blunderous [sic] political attacks” that overstepped the bounds of Congressional authority.

Lewis suggested that the Court’s occasional mistakes were “human failings of a human institution, to be cured by time and the constructive criticism of the bar and the public… The theory is that occasional wrong decisions are the price that must be paid for an independent judiciary.”

On the other hand, Yale law professor Alexander Bickel argued that the showdown taught the Court about the dangers of getting too far ahead of public consensus. As he wrote in his 1965 book Politics and the Warren Court, “Nothing of importance, I believe, works well or for long in this country unless widespread consent is gained for it by political means… The Court must not overestimate the possibilities of law as a method of ordering society and containing social action. And society cannot safely forget the limits of effective legal action, and attempt to surrender to the Court the necessary work of politics.”

Leave a reply to Red and Green Don’t Mix: When the American Legion Declared War on the Girl Scouts – Estes Kefauver for President Cancel reply