What comes to mind when you think of “civil defense”? If you’re under 60, you may not know the term at all. If you do, you might associate it with students diving under desks in hopes of surviving a nuclear bomb. Perhaps you’ve seen cartoons featuring Bert the Turtle reminding you to “duck and cover,” or a sign designating a building as a fallout shelter.

The consensus today is that civil defense was a joke at best and a boondoggle at worst, a relic of Cold War paranoia akin to Joseph McCarthy’s Red Scare. But as Brits who survived World War II can attest, a proper civil defense program is no joke. It can save thousands of lives and be essential to the recovery of a bombed city.

In the 1950s and early 1960s, when nuclear war seemed frighteningly possible, America tried to develop its own civil defense program. Estes Kefauver co-authored the bill that formally established a national civil defense administration. In the years that followed, he repeatedly – and unsuccessfully – pushed the government to take civil defense more seriously.

In the end, little came of the effort. Thankfully, our preparations were never put to the test. But why did civil defense become a public punchline rather than a real program?

I’ve talked previously about how hard it is to get Congress to take potential problems seriously when they aren’t imminent threats. But even when Congress acts, there needs to be follow-through from both Congress and White House to make that action reality. And that happened all too rarely with civil defense.

The Russians Get the Bomb, and America Gets Scared

There were localized attempts at civil defense in America after World War I, mostly in the form of air-raid shelters. During World War II, there were more coordinated efforts, both at the city level (such as the strategic blackouts of cities to deter enemy bombing raids) and nationally (the Office of Civil Defense).

After the war, most efforts were abandoned. Americans were ready to leave the war behind and return to civilian concerns.

But when the Soviet Union had its first successful nuclear test in 1949, everything changed. Suddenly, the possibility of a nuclear bomb hitting the US seemed all too real. And we were unprepared.

The Senate Armed Services Committee hastily assembled a Civil Defense Subcommittee, with Kefauver as chairman. The subcommittee put out its first preliminary report the following month, calling civil defense “one of the most· complex and pressing problems facing the country at the present time.”

The report sketched out a concept of a federal civil defense agency whose role would be to plan and coordinate civil-defense efforts to be carried out primarily at a state and local level. The report recommended making federal funds available for a wide variety of emergency planning and response efforts, from developing evacuation plans and constructing bomb shelters to decontamination and restoration of bombed areas to developing highways and emergency housing.

Kefauver pushed for prompt action on what he saw as a vital issue. That July, he wrote a letter to the chairman of the National Security Resources Board stating, “If it is humanly possible to do so, legislation in this field should be submitted to the Congress prior to September.”

The NSRB submitted its proposed language in mid-September. After incorporating feedback, Kefauver submitted a revised version of the bill at the end of November, authorizing the creation of a Federal Civil Defense Administration to coordinate civil defense efforts with other federal agencies and to provide guidance and funding to states and localities to implement their own civil defense plans.

As Kefauver explained during the hearings on the bill, “[T]he desire of the Federal Government is to co-ordinate and direct and to leave the chief responsibility of actually carrying out the program with the State and with its political subdivisions without us getting into everybody’s hair and in everybody’s way.”

The bill moved with lightning speed by Congressional standards. The bill passed both houses of Congress by the end of December, came out of conference within a week, and was signed into law by President Truman on January 12, 1951.

Kefauver hailed the bill’s passage, and hoped it would accomplish big things. “This program is not merely one of buckets of sand and stirrup pumps,” he said. “It is the creation of a second branch of our defense structure.”

He envisioned America’s civil defense program including “the training of millions of volunteer workers; the accumulation of adequate stockpiles of food and medical supplies to supply likely target areas; the equipping of mobile fire-fighting units to meet the requirements of an atomic bomb burst… the research to develop proper shelters, and ways and means of combatting the terrible after effects of not only atomic weapons but the effects that might come from bacteriological. warfare. In fact, it means the complete mobilization of the minute men and women of our country into a defensive force which will absorb terrific casualties and spring hack into a full productive routine.”

Truman named former Florida governor Millard Caldwell as the FCDA’s first head. It looked like America’s civil defense program was off to a roaring start. But that roar quickly turned into a whimper.

Fun fact: Caldwell was named after Millard Fillmore. No, seriously.

“An Open Invitation for a Surprise Attack”

Almost immediately, the FCDA ran into funding woes. Congress passed the bill quickly, but they weren’t willing to spend much money on it. For fiscal year 1951, Caldwell and the FCDA requested an appropriation of $403 million; Congress appropriated just $31.8 million.

Kefauver worked with Senator Brien McMahon of Connecticut, chairman of the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, to try to increase FCDA’s appropriation, to no avail.

In September 1951, Kefauver held hearings on “the predicament” of the FCDA. He argued that if the government wasn’t going to take civil defense seriously, they shouldn’t bother to pretend. “We should support civil defense or we should quit it,” he said.

In his State of the Union address in January 1952, Truman argued that civil defense was “a major weakness in our plans for peace” and “an open invitation for a surprise attack.”

Fiscal year 1952 brought more of the same: the FCDA requested $535 million, and received just $75.3 million. Truman complained, “It is reckless to evade, under the pretense of economy, the national responsibility for initiating a balanced Federal-State civil defense program.”

Caldwell grew increasingly frustrated. When he published the agency’s first annual report, he added a note to the President sounding off. “It is idle to complain of public apathy in civil defense so long as official apathy is obvious,” Caldwell wrote.

Why did Congress refuse to put its money where its legislation was?

For one thing, the immediate crisis that spurred the FCDA’s creation had eased. The Korean War was grinding toward stalemate; it did not appear that a Soviet nuclear strike was imminent. Also, a big part of the FCDA’s budget request was for construction of bomb shelters, something that key members of Congress weren’t interested in funding.

Caldwell didn’t help matters with his combative attitude toward Congress. During Kefauver’s hearing in September, he got into a finger-pointing spat with the Defense Department over whose fault it was that the government wasn’t taking civil defense seriously enough.

As for Truman, he talked a good game about civil defense, but he didn’t do much to fight for a bigger appropriation. Budgetarily speaking, he had bigger fish to fry.

The FCDA wasn’t off to a good start. And the coming change of administrations didn’t help.

Ike Doesn’t Like Civil Defense

One might think that Dwight Eisenhower would support civil defense efforts. He’d seen first-hand how important they were to Europe during WWII, after all.

In fact, though, Eisenhower was even less supportive than Truman. He wasn’t interested in increasing federal spending; the more that civil defense responsibilities could be offloaded on states and cities, the better.

Also, in Eisenhower’s view, the best defense was a good offense. His administration’s stated policy of “massive retaliation” intended to deter the Soviets from considering an attack on American soil. If there was no attack, there would be no need to plan a response.

Eisenhower’s choice to head the FCDA, former Nebraska governor Val Peterson, shared Eisenhower’s views on limiting the scope and cost of the program. He reasoned that, given the incredible power of the new H-bombs, a city hit with one probably wouldn’t survive. Rather than focusing on building shelters, he wanted to focus on evacuation plans (which, conveniently, would be much cheaper).

Peterson asked for just $150 million in funding (a quarter of Caldwell’s final request). Congress wouldn’t fund even that much; they appropriated just $3.5 million more than they’d given Caldwell the previous year.

However, the FCDA soon faced a new challenge. In early 1955, news broke that deadly radioactive fallout from recent H-bomb tests had spread across hundreds of miles, a far wider area than previously expected. Suddenly, Peterson’s evacuation-based plans didn’t look like such a great idea.

Kefauver held a series of hearings lasting from February through June of 1955. The hearings sought to examine the state of the civil defense effort, particularly given the revelation about fallout.

Displaying a fair amount of chutzpah, Peterson argued that the FCDA needed greater authority to do its job effectively. “FCDA is without authority commensurate with its responsibilities,” he testified. “Authority only to advise, guide, and assist the states is not enough to support positive leadership in a field where direction and control are essential.” The fact that Peterson had not previously wanted or sought such control went unmentioned.

The subcommittee’s report on the hearings pulled no punches. “Due to lack of progress, the country is presently unprepared to deal with a successful H-bomb attack,” the report stated, “with the result that millions of lives possibly could be lost due to the inability to evacuate the cities.”

The report called for the President to assume personal responsibility for America’s civil defense readiness. It also called for increased funding, staff, and visibility for the FCDA, which it said should “assume the responsibility for developing plans for evacuation, mass feeding, and for the medical care of people in case of an attack.”

The publicity generated by the Kefauver hearings (and House hearings held the following year by California Rep. Chet Holifield) embarrassed the FCDA into increasing its sense of scope and Congress into coughing up some more money (though still not as much as requested). But it didn’t spur the changes Kefauver hoped to see.

Eisenhower took no personal responsibility for civil defense. Holifield’s proposal to make the FCDA a Cabinet-level department went unheeded. The administration reluctantly looked into a limited program for constructing fallout shelters, but never took it seriously.

In response, the Senate… got rid of the Civil Defense Subcommittee, and didn’t replace it. (Senators Hubert Humphrey and Stuart Symington suggested a House-Senate Joint Committee on Civil Defense; this proposal was ignored.) Neither Congress nor the White House planned to take civil defense seriously; they didn’t need Kefauver reminding them about it.

The Civil Defense Flame Flickers Out

Civil defense had a rocky road in the decades that followed. In 1958, the Eisenhower administration combined the FCDA with the Office of Defense Mobilization into the Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization. But Eisenhower remained just as uninterested, and Congress continued to underfund it.

Civil defense enjoyed a brief revival under President Kennedy; he stood up an Office of Civil Defense within the Pentagon and made a real push to fund it. Amid the Berlin Crisis and the Cuban Missile Crisis, Congress finally appropriated the full amount requested in 1961 and 1962.

But it didn’t last, and funding slid back to previous levels through the ‘60s and ‘70s. President Carter placed civil defense responsibilities under FEMA, where they remain today. President Reagan attempted another revival of interest in civil defense in the ‘80s, but it went nowhere.

Epilogue: An Ounce of Prevention

When assigning blame for America’s failure to implement a serious civil-defense program, there’s plenty to go around.

The original Federal Civil Defense Act was rather vaguely worded, leaving major questions about the FCDA’s reach and jurisdiction. (Kefauver mentioned repeatedly during the hearings on the Act that the law was imperfect and that he expected it to be improved over time. He failed to foresee that wouldn’t happen.)

As described above, Presidential disinterest and underfunding from Congress hamstrung civil defense efforts. The heads of the FCDA and successor agencies also generally struggled to articulate a vision for civil defense and defend their appropriation requests. And the public only cared when it appeared a Soviet attack might be imminent.

The idea of civil defense being directed at the federal level and executed at the state and local level also created problems. Perpetual debates over how to divide up responsibility, initiative, and funding dogged the efforts from the beginning and made it easier to point fingers when things went wrong.

In short, the story of civil defense in America shows how difficult it can be to plan for an potential catastrophe on an undetermined timeline. As a country, we’re good at rising to an emergency, but not so great at preventive planning to keep that emergency from happening.

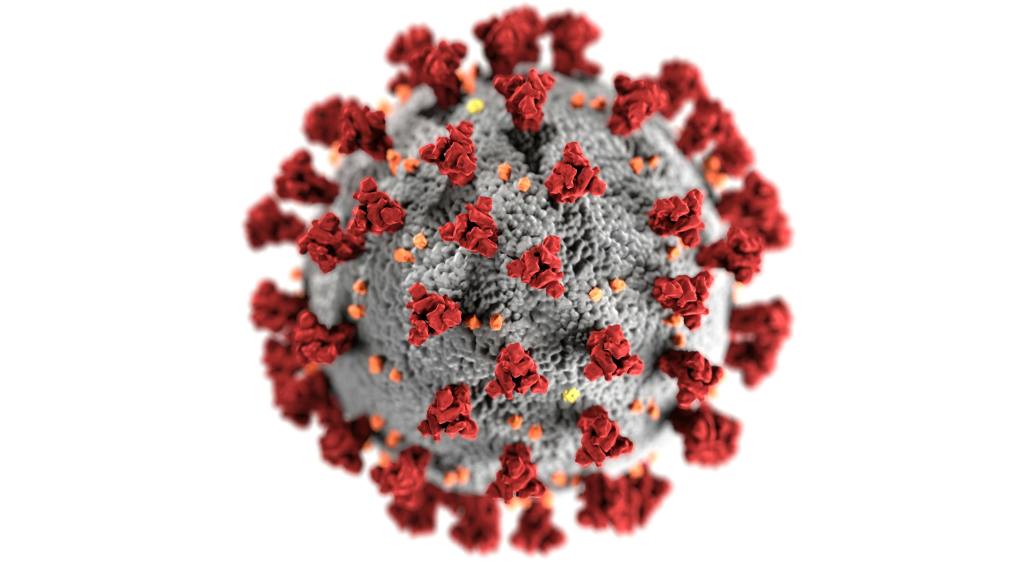

Lest we think that this story is a relic of a past era that doesn’t apply to us now, consider the state of our pandemic planning.

Despite decades of warnings from specialists in infectious disease, America was ill prepared when COVID-19 swept our shores. And even after we lived through the pandemic and the millions of deaths and national disruption it caused, we’re little better prepared for the next deadly outbreak.

An ounce of prevention miay be worth a pound of cure, but America has shown time and again that we won’t pay for prevention. Evidently, it’s easier to pretend that a major disaster couldn’t happen here… until it does.

Leave a reply to No Misery in Missouri: Kefauver Charms the Show-Me State in ’56 – Estes Kefauver for President Cancel reply