Haste and fear are rarely the ingredients of good lawmaking. There have been numerous laws over the years that were passed in a rush due to some (real or perceived) emergency; in many cases, those laws wind up being poorly drawn, over-broad, and difficult to enforce.

Imagine, if you will, a law drawn up in over the course of a couple short months at the end of a busy Congressional term. This law was demanded by the FBI and the Justice Department on an emergency basis in reaction to what they called a national security emergency caused by a Supreme Court decision. Congress, already itching for a reason to slap back at the Court for perceived overreaching, was all to happy to comply. They barely held hearings on the bill and limited floor debate to a couple hours, all so that could ram the bill through before adjourning for the year.

This is the story of the Jencks Act. It’s a bad law that was passed for bad reasons. And yet, it still remains law to this day, demonstrating just how hard it is to get rid of a law once it’s passed.

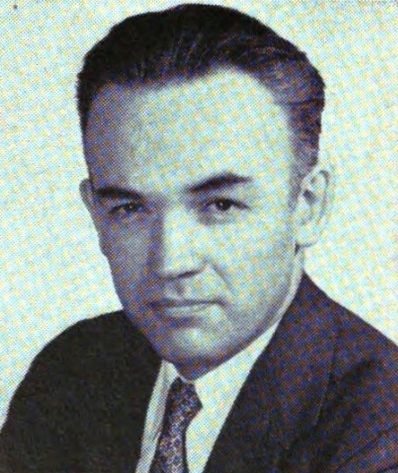

There were only a handful of lawmakers with the courage to stand up and oppose this. Estes Kefauver was one of them. Sadly, as was often the case, he couldn’t get his colleagues to listen.

Labor Leader Leaves the Government Seeing Red

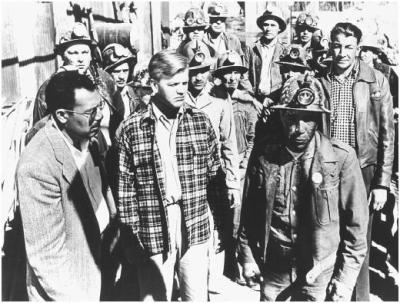

Clinton Jencks was a labor organizer. In the late ‘40s, he went down to New Mexico to become the president of Local 890 of the International Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers. The local represented a group of mostly Mexican-American zinc miners in southern New Mexico.

Jencks and his union struck against the Empire Zinc Company, which ran the mines, demanding higher wages and more safety protections. After the company’s union-busting tactics (which involved attacks by company thugs and jailing of union leaders) failed, they secured a court injunction preventing the miners from setting up a picket line to prevent scabs from entering the mines. The miners, with Jencks’ encouragement, responded by having their wives take over the picket line. After a multi-year battle, the union won.

(It’s a great story, and if you’re interested, I encourage you to watch the 1954 film Salt of the Earth, which is a lightly fictionalized account of events starring Jencks and other real-life members of Local 890. But it isn’t the point of this story, so we’ll move along.)

Naturally, this union victory couldn’t be allowed to stand. So the government went to its go-to tactic for disrupting unions: accusing the members of being Communists. Jencks was arrested for lying on an affidavit (required by the anti-union Taft-Hartley Act) stating that he had no association with the Communist Party.

The government’s case included no direct evidence that Jencks was a Communist (for instance, a roster of Communist Party members with his name on it, or records of his attending a party meeting). Instead, their case relied on the testimony of two witnesses, Harvey Matusow and J.W. Ford, who told the FBI they had seen Jencks participate in meetings and discussed membership with him.

How did the government get away with such a thin case? For one thing, it was 1954 – right around the peak of the Red Scare. Second, according to the testimony of Matusow and Ford, the Communist Party directed that membership of prominent figures, such as union leaders, be kept a secret. Therefore, of course there were no records of Jencks’ involvement!

Oh, did I mention that Matusow and Ford were both paid FBI informants? And when Jencks and his lawyers asked to see the FBI’s reports regarding Matusow’s and Ford’s statements, the judge rejected the motion? No matter, nothing to see here; Jencks was clearly guilty. Case closed!

There was just one tiny little problem: Matusow was lying. In addition to being a paid FBI informant, Matusow was also an aide to the ever-repugnant Senator Joseph McCarthy.

In 1955, he wrote a book called False Witness, in which he admitted that he had repeatedly perjured himself making false accusations of Communism in court. He even devoted a whole chapter specifically to the Jencks case, titled “Witness for the Persecution.” In it, he admitted – surprise! – that he’d lied about Jencks.

Armed with Matusow’s book and other evidence, Jencks promptly demanded a new trial. Both the district court and the Court of Appeals both denied his request, and Jencks took his case all the way to the Supreme Court.

In a 7-1 ruling in June 1957, the Court held that the judge in Jencks’ original trial was wrong to deny his request to view the FBI’s reports. They tossed out Jencks’ conviction, and held that defendants were entitled to see any written or recorded oral statements related to witness testimony or the events at trial. If the government believed that they couldn’t share the pertinent records for national security reasons, then they had to abandon prosecution.

The lone dissenter, Justice Tom Clark, dissented hard. He claimed that the ruling meant “those intelligence agencies of our Government in law enforcement may as well close up shop, for the Court has opened their files to the criminal and thus afforded him a Roman holiday for rummaging through their confidential information as well as vital national secrets.” He called on Congress to pass a law expressly to limit the Court’s ruling.

Congress was about to heed Clark’s call.

Don’t Just Stand There, Do Something!

In response to the Court’s ruling in Jencks vs. U.S., both the FBI and the Justice Department panicked.

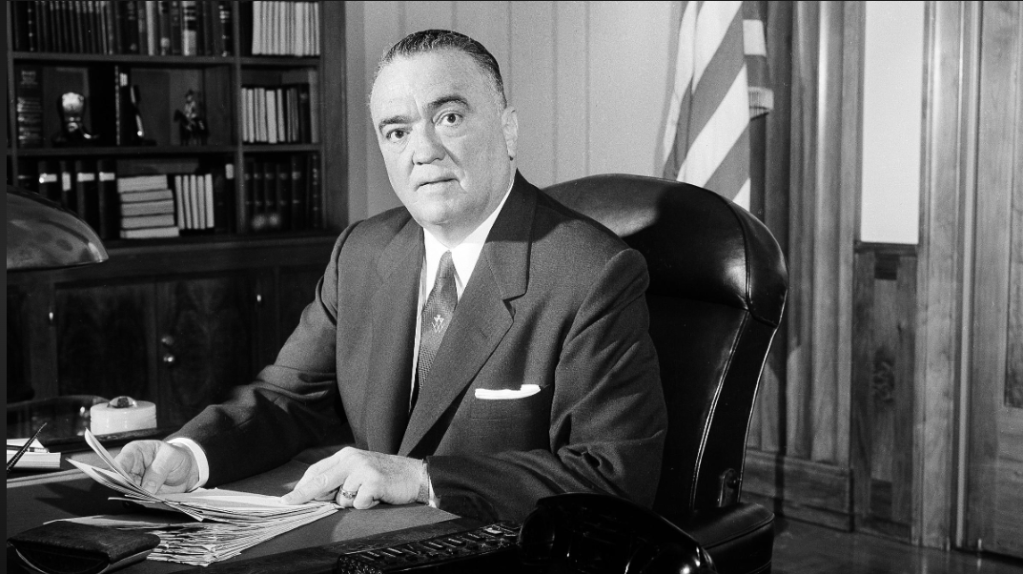

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover was famously obsessed with secrecy, and the idea of letting a bunch of dirty criminals get their hands on the Bureau’s precious files terrified him. He argued that giving defendants the right to view FBI files would disclose the Bureau’s methods and potential targets of investigation, reveal the names of confidential informers – potentially putting their lives in danger, and risk public exposure of uncorroborated hearsay in the FBI’s files that could damage the reputations of innocent people (and, more importantly, embarrass the Bureau).

In a letter to House Republican Leader Joe Martin in August of 1957, Hoover claimed that “[w]e have experienced instance after instance where sources of information have been closed to our agents because of the fear that the confidence we could once guarantee could not longer be assured. We have also experienced a reluctance on the part of numerous citizens to cooperate as freely as they once did.”

Attorney General Herbert Brownell was equally hyperbolic, calling the Jencks ruling “a grave emergency in federal law enforcement” and said that it provided “an instructive course in how to evade federal law enforcement officers in the future.”

Both Hoover and Brownell expressed fear that the Court’s ruling would allow defense attorneys unlimited access to FBI a files, allowing them to go on “fishing expeditions” to embarrass or discredit the government. They claimed that lower courts were already interpreting the Jencks ruling to hold that prosecutors must turn over all FBI records in their possession to the defense. They made this claim in spite of the fact that the Court specifically limited its ruling only to reports and transcripts with direct bearing on witness testimony or the facts of the case.

The problem was that the Court’s ruling came out in June, and Congress was due to adjourn for the year at the end of August. Was there really enough time to consider the bill in committee, hold proper hearings, get input from a variety of sources, hash out the legal technicalities, and pass a well-crafted bill in less than three months?

The answer: No, there wasn’t. But there was enough time to slap together a hastily-considered bill and ram it through Congress. After all, this was an emergency! The FBI said so, and they would never lie about such things. As Anthony Lewis wrote in the New York Times during the bill’s whirlwind creation, “The FBI has always been extraordinarily popular with Congress, and security-consciousness has not lost its political appeal.”

It’s worth noting that conservatives in both parties were already unhappy with the Warren Court. Southern Democrats were still pissed about the Court outlawing school desegregation in Brown v. Board, and conservative Republicans were angry about the Court’s insistence on protecting the civil liberties of accused Communists and seditionists. They were itching for a chance to stick it to the Court, and Hoover and Brownell offered a golden opportunity to do so. After the bill passed, Lewis attributed its swift progress primarily to “Congressional feelings of antagonism toward the Supreme Court.”

From practically the moment the Court’s decision came down, Congress was off to the races. The first bill to limit the scope of the Jencks ruling was filed the very next day. Both the House and Senate quickly referred the bills to their respective Judiciary Committee. Neither held any public hearings, and together they took testimony from a grand total of two witnesses: the Attorney General and his deputy. The American Bar Association was not consulted; nor were any judges, law professors, or attorneys in private practice.

The House Judiciary Committee flung its bill onto the floor first, with language practically dictated by the Attorney General’s office. The House further sped the process along by limiting floor debate to a single hour. As Lewis noted, the House debate “was given over to demagogic denunciations, and no one on either side addressed himself to the real issues in the legislation.”

In fairness, freshman Rep. Frank Coffin of Maine managed to wedge in some astute observations about the absurdity of the process. “In a near frenzy over the prospect of delay or acquittals during the next several months,” Coffin said. “we set ourselves the task of legislating a rule of court, during the last-minute rush of the session, without having conducted any hearings in depth, without seeking or gaining the reasoned advice of bench and bar.”

He concluded sarcastically that “allowing only one hour of general debate, we expect to add to the dignity and effectiveness of our system of justice.”

Rep. Emmanuel Cellar of New York called out the FBI for exaggerating the need for a law and accused Hoover of producing “great waves of propaganda.” Nevertheless, the House passed the bill overwhelmingly.

The Senate, to its credit, took the assignment at least a bit more seriously. Oregon’s Wayne Morse and Pennsylvania’s Joseph Clark, both lawyers themselves, raised salient objections to the bill as proposed by the administration. Senator Joseph O’Mahoney of Wyoming, a member of the Judiciary Committee, wound up crafting a bill that at least nodded in the direction of defendants’ rights and the rules of criminal procedure. (In response, Acting Attorney General William Rogers slammed the Senate bill as inadequate, saying that it “contributes little, if anything, to meet the legislative need.”)

After the Senate passed O’Mahoney’s bill, it moved to conference committee. There, the conferees added new language that was not present in either the House or Senate version of the bill. It specified that the only items the defense was entitled to receive were written statements approved or signed by the witness, and verbatim recordings or transcripts of oral statements made by witnesses. It excluded any related records relevant to the case. (Also, the prosecution was not required to provide these statements until after the witnesses in question had already testified, severely limiting their usefulness.)

The conference version of the bill also removed any mention of the federal rules of criminal procedure (always a good sign in a bill about federal criminal law!). The conferees claimed that this was to ensure that there was no possible way for defense attorneys to argue that they should be allowed to examine the documents prior to trial.

The conference version of the bill came up for a final vote on August 30th, the very last day of the session before adjournment. Weary and ready to go home, the Senate voted to approve the final version 74-2.

The two “no” votes were North Dakota’s William Langer… and Estes Kefauver.

Kefauver was no stranger to being on the losing end of lopsided votes, and this was one. He had voted for the O’Mahoney bill, but the changes to the final version were beyond what he could accept.

“The bill as it passed the Senate regulated handling of both statements and records,” he explained. “But in the joint Senate-House Conference the bill was rewritten. It defined what statements were, but seemed to leave records – like photostats, checks, and pictures – in a no-man’s land. As I interpret the bill it may be either unconstitutional or leave the defense in trials without any recourse to FBI records.”

Kefauver’s brave stance went over poorly with conservatives. His home-state Knoxville Journal claimed that “Tennesseans were embarrassed” by his vote, and noted that the Americans for Democratic Action, “that good old reliable band of left-wingers among whom Senator Kefauver has many friends,” was also opposed to the bill.

“It’s that old left-wing streak that shows up regularly in Senator Kefauver’s public attitudes,” the Journal concluded, “and it’s the thing that has placed his political standing in the state at its low ebb.” (Low ebb or not, Kefauver was re-elected overwhelmingly three years later; clearly, the voters didn’t hold it against him.)

It Keeps Going and Going…

History has not viewed the Jencks Act favorably. Critics have pointed out that because of it, defendants in federal civil cases have much broader discovery rights than in federal criminal cases, where their lives and liberties are at stake. Defense attorneys have noted that if they cannot review witness statements until after witnesses have testified, it’s hard to effectively cross-examine those witnesses.

Also, to Kefauver’s point, the fact that the prosecution is not required to turn over records and notes related to the witness statement makes it difficult for defense attorneys to determine whether a witness’s story has changed over time to match the prosecutions case.

Worse yet, if the government fails to comply with a request for documents, courts tend to treat this as a “harmless error,” rather than as ground for a mistrial, as the Supreme Court’s decision held.

In their 2019 New York Law Journal article, Darren Laverne and Jessica Weigel condemn the impact of the Jencks Act: “A defendant is kept in the dark, until he is engaged in the crucible of trial, regarding what is often the most critical evidence—what the witnesses against him say.” Philip Jobe and Marc Greenwald had an even harsher criticism in 2022, calling the Act “unworkable, unfair and un-American.”

The primary disagreement among the Act’s many critics is whether the Act needs to be amended, rewritten, or thrown out entirely. A decade ago, the ABA called for a significant revision of the Act, broadening the definition of “statements” that prosecutors must turn over and stating that prosecutors must turn them over “upon request… without delay and prior to the entry of any guilty plea.”

Despite the numerous criticisms of the Act, removing or even amending it has proven to be challenging. In 1985, Rep. John Conyers of Michigan attempted to modify the Act to require prosecutors to provide the names and addresses of anyone known to have information regarding the facts of the case, and to make them available promptly, upon the defendant’s request. (As with the ABA’s proposed revision, if the prosecutor believed that disclosing the information would threaten the safety of a witness, they would have to demonstrate this to the court to obtain a protective order.)

Conyers’ amendment was backed by the ABA, the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, and multiple other groups. But the Justice Department opposed it, and that was enough to kill it. And so far, nothing has come of the effects to reform or abolish the Act in more recent years.

Unfortunately, once a bad bill becomes law, it’s hard to get rid of it. No matter how bad it is, defenders will find an excuse to support the status quo. And unless it’s an emergency, it can be hard to get Congress to act (a lesson Kefauver also knew well).

For over 75 years, defendants in federal criminal cases have labored under the strictures of a poorly-written bill rushed into effect because of a toxic stew of an alleged national security emergency, Congressional resentment against the Court, and lingering anti-Communist paranoia. For all the times Kefauver was frustrated by his colleagues’ unwillingness or slowness to act, this is one time he was right to counsel patience.

Leave a reply to Better Living Through Chemistry: Kefauver and the Department of Science – Estes Kefauver for President Cancel reply