Estes Kefauver was, by the standards of politicians, a prolific author. He authored numerous articles in scholarly journals (some of which we have discussed here) as well as three books, each aimed at persuading the public of the importance of issues that mattered to him.

Kefauver was as prodigious a reader as he was a writer. He regularly read books on issues that came before him as a Senator. And on at least one occasion, he read a book that moved him to the point of addressing legislation based on it.

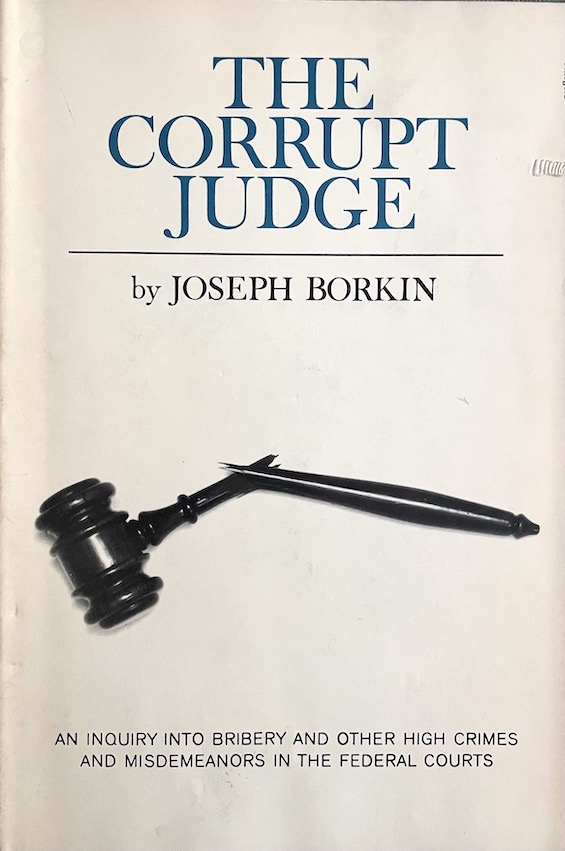

In 1962, author Joseph Borkin wrote a book called “The Corrupt Judge,” which was about… well, corrupt judges (specifically at the federal level). It was a subject that Borkin knew well: he had been an attorney for the Department of Justice before changing fields.

The book focused primarily on the stories of three federal judges who resigned under pressure after having been found to engage in corrupt activities. The first, a circuit court judge named Martin T. Manton, resigned in 1939 after he was caught accepting gifts and loans from people with business before him in court. The second, another circuit court judge named J. Warren Davis, resigned after being indicted for accepting a bribe from film producer William Fox (the same one 20th Century Fox is named for). The third, Pennsylvania district judge Albert Johnson, resigned in 1945 after being investigated by the House Judiciary Committee (on which Kefauver served at the time).

In addition, Borkin performed a study of 32 cases where federal judges were investigated by Congress for a variety of reasons (not just financial corruption, but other issues such as biased ruling or intoxication on the bench), to see if he could identify any patterns in the types of judges who were most susceptible. Borkin found no particular pattern.

Kefauver read “The Corrupt Judge,” and he was stunned by what he read. He wrote a review of the book in the New York Times in December 1962, calling it “an eye-opening shocker” and “truly a block-buster.”

Kefauver’s review highlighted the importance of being able to rely on the honesty and integrity of judges. “Under our delicately balanced system of government, the judge plays a singular role in keeping with the doctrine of judicial supremacy,” he wrote. “Figuratively and literally, he has been placed on a pedestal above the rest of us.”

Kefauver argued that while only a handful of judges engaged in corrupt behavior, the public knew virtually nothing about the cases that did occur. (This wasn’t just speculation on Kefauver’s part; he’d asked the Library of Congress to send him books or journal articles about judicial corruption, only to be told that they had none.) And he placed the blame for that on the legal profession, which he said engaged in a “’conspiracy’ of silence” on the issue.

Kefauver wrote that “the legal profession is loath to dwell on past examples of corruption.” He said that lawyers who talked to openly about the possibility of judges being corruptible “would be considered indiscreet by their colleagues – and, worse, their clients might be frightened away.”

But even worse, from his perspective, “is the unwillingness of lawyers to help the authorities by testifying about their knowledge of corruption. The reason for this, of course, is fear of retaliation.”

Kefauver also highlighted Borkin’s point that no one type of judge was more likely to engage in corruption than another. “Their backgrounds range from theological seminaries to Tammany politics from honor graduates and trustees of great universities to associates of gangsters,” he noted.

Manton had been considered for a Supreme Court seat by Warren Hardin, while Davis had been a scholar and a minister before turning to the law. Their distinguished backgrounds and credentials didn’t prevent them from going down the same road as Johnson, a political hack whom the House Judiciary Committee blasted as “a wicked and mendacious judge.”

The one commonality Borkin found was that “judicial corruption is often connected with economic down-turns.” That was the case for Manton and Davis; the former began accepting gifts when he ran into financial trouble during the Great Depression, while the latter was bribed because Fox feared losing his studio in bankruptcy proceedings.

Borkin’s most serious charge, in Kefauver’s eyes, was that there was a two-tiered system of justice for corrupt judges. He quoted Borkin decrying “the selective application of the [judicial] Canons, with one code for the Brahmins of the law and another for its lesser servants, with a soft impeachment for knavery on the grand scale and a swift, harsh discipline for the fumblings of the petty shyster.”

Kefauver noted that this sadly comported with his own experience. Once, a Judiciary Committee hearing turned up clear evidence that an attorney bribed a judge. Kefauver forwarded the hearing transcripts to the New York State bar association, along with a request that the lawyer be punished. “The man in question was a very prominent ‘Brahmin.’ I was not even given the courtesy of a reply,” he wrote. “Had he been of lesser stature, I am sure the response would have been prompt and affirmative.”

How to address the problem? Borkin, noting that the connection between corruption and financial trouble, proposed that all federal district and circuit court judges be requirement to file financial disclosure forms with the Supreme Court.

Kefauver credited Borkin for “a courage rare even among legal scholars” both in describing the issue and suggesting a remedy. He added that he was so taken with Borkin’s suggestion that he would propose it as legislation to the Senate.

And indeed he did. Kefauver’s proposal would have modified the conflict of interest statute for federal judges to require them to file financial disclosures on an annual basis. Unfortunately, his colleagues had evidently not read Borkin’s book, or else they didn’t see it the problem as acutely as Kefauver did, because they took no action on it. It wasn’t until 1978 and the passage of the Ethics in Government Act that federal judges were finally required to file financial disclosures.

One of the things that made Kefauver stand out as a politician was his willingness to listen. If somebody made a compelling argument that he was wrong on an issue, he would listen and possibly change his mind. And if he read a book that made a strong case, he was willing to try to turn it into law.

Leave a comment