Estes Kefauver was a reformer at heart, always looking for ways for the government to be more efficient and better serve the people. One of his more intriguing ideas was to create a federal Department of Consumers.

This proposal, which he would champion the last few years of his life, never came to fruition. But its spirit lived on through the consumer protection movement that became a major force in America in the 1960s and 1970s.

A Voice for the Economy’s Forgotten Man (and Woman)

Kefauver first floated the idea in an article entitled “A Voice for Consumers,” in the January 1959 article of The Progressive magazine. The idea flowed out of the hearings he had held as chairman of the Senate Antitrust and Monopoly Subcommittee, examining the phenomenon of “administered prices” – that is, prices that were set by the dominant firms in an industry, rather than by the market forces of supply and demand.

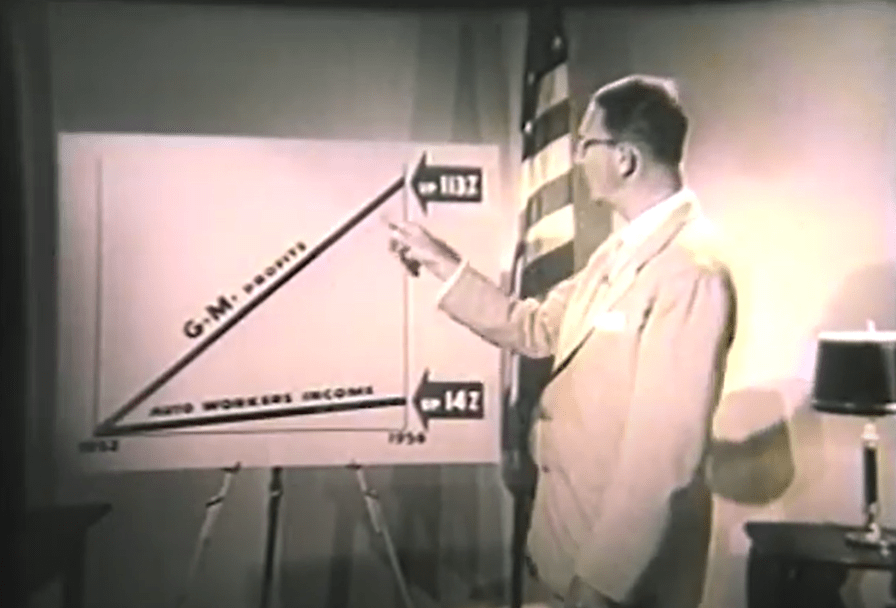

“As we look at the American economy today and see industry after industry firmly controlled by the Big Two, Big Three, or Big Four,” Kefauver wrote, “it is apparent that excessive concentration is something which is no longer merely a threat of the future; it is a present reality.”

Kefauver felt that a Department of Consumers could provide “for effective representation in government of the consumer’s interest.” He pointed out that the government had departments to represent businesses, farmers, workers – all of them producers. But there was no equivalent department representing consumers.

Such a department would, Kefauver believed, provide a check on inflation. “The managers of large corporations would, in my opinion, think twice before making a price or rate increase,” he wrote, “if there existed an adequately staffed, vigorous agency which might view their action as onerous to consumers and illegal under the antitrust laws, or unwarranted under the regulatory statutes.”

This was something only the government could do, he argued, as it would be difficult to create an consumer organization similar to business lobbying groups or labor unions. “Since it is unlikely that consumers can be organized… [o]nly through the establishment of a Department of Consumers will the voice of the consumer be heard in the land,” Kefauver concluded.

That March, Kefauver presented his Department of Consumers bill before the Senate. In his speech introducing the bill, Kefauver argued that the concentration of industries among a few big firms meant that prices “have become largely immune to the normal forces of supply and demand. Thus the American consumer is being denied that protection which it is assumed… will adequately protect him, [that being] the unseen hand of competition.”

Kefauver argued that the existing representation of consumers within the government was “limited, fragmented and relatively ineffectual.” The Department of Consumers would change that.

The proposed department would represent the consumer’s viewpoint during the formulation of government policies, as well as speaking for consumer interests before the court and to regulatory agencies.

“The number and variety of different governmental policies which have a real and direct impact upon consumers is virtually infinite,” Kefauver said. Consumers would benefit from a voice within the government to point out the impact of those policies before they went into effect.

Kefauver also envisioned the department as a national clearinghouse for consumer complaints. “Today, even where he has a complaint of the most legitimate type,” he said, “the most informed consumer can be excused for not knowing to which of the numerous government agencies he should address himself.” The department would either address the concerns, if within their purview, or route them to the proper agency for action.

The department would also conduct investigations into productive capacity, price levels, quality of consumer goods, and economic conditions from a consumer point of view. This would benefit not only the public, but Congress as well. “It is often difficult for Congress, in considering legislation, to evaluate its effect upon consumers,” Kefauver said. “This is a type of information which is frequently most difficult to obtain.”

Noting the recent formation of state consumer protection agencies, he recommended that the Department hold an annual National Consumers Conference with those agencies and other consumer advocates to provide and receive advice and assistance on how best to protect consumers.

The department’s operating responsibilities would largely be repurposed from other agencies. Kefauver proposed reassigning the FDA to the Department of Consumers, as well as the responsibility for calculating the Consumer Price Index and the Department of Agriculture’s home economics bureau.

Kefauver argued that combining these functions under a single umbrella would not only be more efficient, but would improve employee productivity and morale, since they would be working for a unified purpose. To critics who feared that the department was a pretext for imposing wage or price controls, Kefauver pointed out that his proposal did not give the department that power.

A Promising Start Fizzles Out (Thanks for Nothing, JFK)

Kefauver’s bill was greeted favorably. He attracted over 20 co-sponsors from both parties, and the proposal was referred to the Senate Subcommittee on Reorganization and International Organizations (chaired by Hubert Humphrey, one of the bill’s cosponsors), which held hearings on it in June 1960. The prospects looked bright.

But then the bureaucracy struck back. Almost all existing federal departments and agencies – whether or not the proposal impacted them directly – weighed in against the bill. They argued that “consumer interests” were too broad an area to belong to a single department; all departments and agencies across the federal government, they said, were responsible for protecting consumers.

They argued that giving a Department of Consumers the power to comment on other agencies’ regulations would create jurisdictional issues, generate confusion, and threaten the agencies’ independence. Worse yet, giving them the ability to speak for consumers in court might lead to two different lawyers speaking on behalf of “the government,” but arguing opposite sides of the issue.

As for transferring existing functions to the new department, this would disrupt inter-departmental cooperation and split up functions that made more sense together. Any possible benefits, the bureaucrats concluded, would be outweighed by the complications and expense of reorganization.

Government agencies weren’t the proposal’s only critics. The National Retail Merchants Association bashed it as an unnecessary bureaucracy that served no real purpose. After all, they said, retailers looked out for the consumer interest. “[A]ny retailer who fails in performing his responsibility as a purchasing agent for the consumer,” the NRMA argued, “does not last very long on the American scene.”

Other critics argued that the proposed department didn’t have enough operational responsibilities to make sense as a Cabinet-level department, and that it would make more sense as an agency. Others argued that the department would essentially function as a lobbying agency within the government, and that the President wouldn’t stand for an arm of the government pushing for more aggressive consumer action than the administration already supported.

Kefauver’s bill died when Congress took no action on it before adjourning in 1960. Undaunted, Kefauver refiled it in 1961 with the new Congress. With a Democratic administration in the White House, he hoped he might get some help from the executive branch.

That hope turned out to be misplaced. President Kennedy gave the first-ever Consumer Message to Congress in 1962, in which he argued that consumers have several rights, including the right to be heard.

However, he made no mention of Kefauver’s proposal; instead, he called on Congress to grant the ability to create product safety regulations and take action to combat monopolies. He also appointed a Consumer Advisory Committee as part of the Council of Economic Advisors.

Congress again failed to act on Kefauver’s bill before the end of session. In June 1963, Kefauver filed the proposal once again. This time, responding to critics of the idea of a Cabinet-level department, he instead proposed an Office of Consumers, to be headed by a Consumers Council. This office would still have the same mission and most of the same proposed functions as his prior Department of Consumers.

After Kefauver: More Progress, But Nixed by Nixon

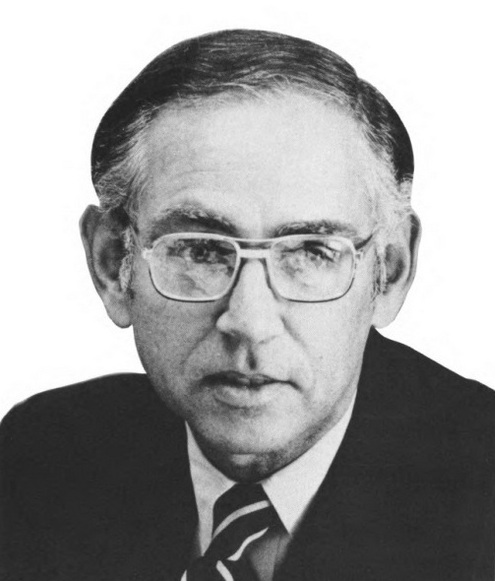

When Kefauver died in August 1963, the proposal lost its greatest champion. Unlike some of Kefauver’s other proposals, however, there were others willing to carry on the fight after his passing.

One of the idea’s chief champions was New York Rep. Ben Rosenthal, who made consumer protection his signature issue. In 1965, he refiled Kefauver’s original Department of Consumers bill, and did so again in 1967.

In 1969, Rosenthal teamed up with Wisconsin Sen. Gaylord Nelson to refile the bill, this time calling for a Department of Consumer Affairs. After feedback from consumer advocate Ralph Nader, Rosenthal rewrote his bill to establish an independent Consumer Protection Agency.

Over the two-year session, multiple Senators and Representatives files dueling bills proposing various structures for a federal consumer protection organization. The Senate managed to pass a bill, but the House Rules Committee deadlocked and failed to report their bill out.

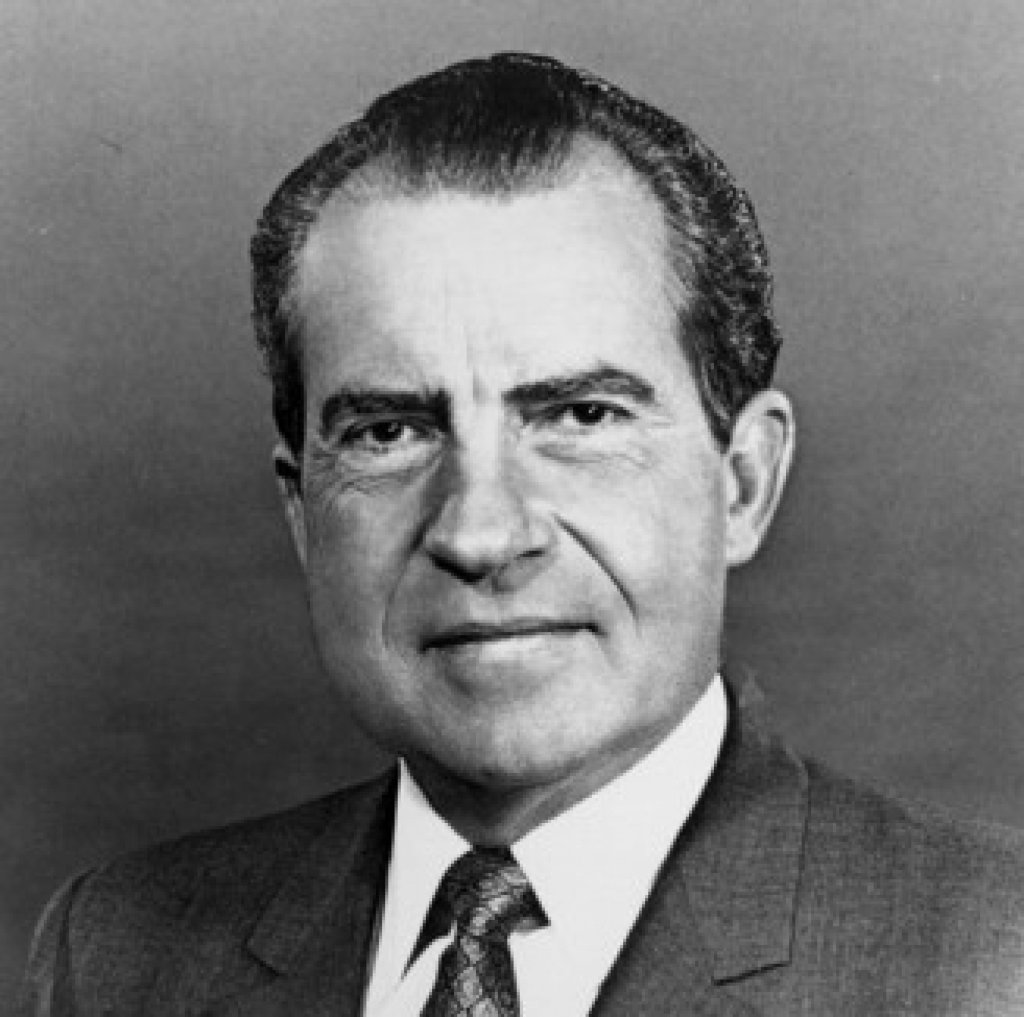

In 1971, again there were multiple competing bills in the House and Senate. The House effort wound up in the hands of Rep. Chet Hollifield of California, who crafted a bill for a limited version of Rosenthal’s CPA; it was backed by the Nixon administration and passed overwhelmingly.

In the Senate, a more expansive CPA bill died after a long filibuster. The Senate bill’s bipartisan sponsors blamed the administration. They said that they’d agree to amend their bill to match the House bill if the White House would support an cloture; the administration abandoned the idea, and the bill died. (Jimmy Carter tried to revive the idea during his term, but Congress wouldn’t go along.)

All was not lost. In 1972, the same year that the CPA bill died, Congress passed an act creating the Consumer Product Safety Commission.

And consumers did start to get organized. Ralph Nader founded Public Citizen and successfully pressured the Nixon administration to beef up the consumer protection and antitrust functions of the Federal Trade Commission. Lobbying organizations like PIRG sprung up to advocate for consumer protections. State consumer protection agencies performed some of the functions the Department of Consumers would have, albeit at a lower level.

Postscript: A Flawed but Worthwhile Idea

Was Kefauver’s federal Department of Consumers a good idea? As usual, the devil is in the details. I think Kefauver’s original proposal, in which the department largely lobbied other parts of the government on the consumer’s behalf, wouldn’t have worked. In all likelihood, the department’s input would have largely been ignored.

(It didn’t help that “consumer” was a female-coded role at the time. To his credit, in his speeches Kefauver regularly pointed out that women made most consumer purchases in most households. But that probably made it easier for male-dominated Washington to consider consumer issues “woman’s issues” and take them less seriously.)

Left to right: Esther Peterson, Betty Furness, Virginia Knauer.

However, I think the idea could have been workable with some tinkering. (Kefauver was open to modifications, as long as the result served his intended purpose of providing a voice for the consumer interest in the government.)

In 1967, a trade lawyer named W.E. Forte analyzed the proposal in the Vanderbilt Law Review. Forte thought the idea of a Department of Consumers was sound, but he felt that the concept would best be executed by combining the FDA with the consumer protection functions of the FTC.

The new department would be responsible for ensuring truth in labeling and ads, inspecting factories, and setting overall government standards for consumer products (especially foods). The FTC’s antitrust responsibilities would be reassigned to the Justice Department, and a “trade court” could be set up to assume the FTC’s adjudicative responsibilities.

Forte’s proposal makes sense to me, and it would have given the proposed department a scope more comparable to other departments.

Details aside, I think Kefauver was right – and arguably prescient – to call for official representation of consumer interests. America’s understanding of itself as a nation of consumers has only grown since Kefauver’s day. And although the consumer-protection movement has faded since its heyday in the ‘70s, the more recent debate over the establishment of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau shows that these issues are as vital – and controversial – as ever.

Leave a reply to Nothing Succeeds Like Succession: Kefauver and the 25th Amendment – Estes Kefauver for President Cancel reply