Last week, I made the argument that Kefauver should receive credit for pioneering the modern style of Presidential primary campaigning. While doing research for a future article, I was delighted to see the same argument made by one of the deans of Presidential campaign journalism.

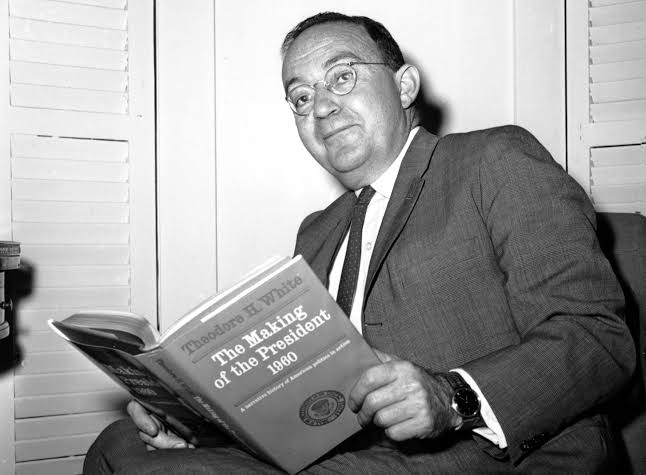

Theodore H. White is best remembered today for his The Making of the President book series, which spanned from 1960 until 1972, providing thoughtful insights into the candidates, the significance of the elections, and how they reflected the larger American culture. The Making of the President 1960 is still considered the definitive work on that election.

In 1980, White wrote a book called America in Search of Itself, reflecting on his quarter-century of political reporting and how dramatically campaigning had changed in that time, using the Reagan-Carter election as a backdrop.

In that book, he looked back at the 1956 campaign, the first one he covered. And he made the case that that election – thanks in large part to Kefauver – marked the start of a new chapter in Presidential campaign history.

“Estes Kefauver,” he wrote, “should be recorded as the godfather of the presidential primary system.” What’s more, White said the 1956 campaign began “the institutionalization of the presidential primary gauntlet, which was to make conventions almost obsolete as nominating gatherings, and reshape all national politics.”

White got to experience this reshaping up close as he followed Kefauver around, beginning in New Hampshire. He noted that only seven reporters followed Kefauver (the only candidate actively campaigning) on the weekend before the primary. He said that the tiny press gaggle in 1956 “seems now, in retrospect, like a sheriff’s posse” in comparison to the phalanx of correspondents covering the Granite State in 1980, a number he estimated around 1,000.

White noted that although Presidential primaries had existed since the early 1900s, they “had been almost entirely ornamental” before Kefauver came along. The Tennessee senator, White wrote, “was the first man to see primaries as the corridor to power.”

White also recognized that this was Kefauver was trying the only path available to him. “Kefauver… had no friends among the power brokers,” he wrote. “[P]rimaries were his only road to the Democratic nomination; he yearned for that nomination[.]”

White also said that Kefauver was “the first man to recognize how, in the dawning age of television and quickening social conscience, a ‘down-home boy’ could use the primaries to appeal to ordinary people over the heads of their anonymous ‘bosses.’” He considered Kefauver’s run “a challenge to the old party system, an appeal directly to the people, coast to coast.”

Looking back from his vantage point in 1980, White said “it is still amusing to recall the quality of Estes Kefauver’s exercise in New Hampshire that year.” He noted what a quaint endeavor Kefauver’s New Hampshire campaign was, compared to those that would come later.

“Kefauver had no private chartered plane, no attendant staff,” he wrote. “He traveled with no speech writers. Accompanied occasionally by a young briefcase carrier from Washington, he was entirely dependent on local volunteers to get him to and from meetings and airports… Through the slush and snow he slogged, through each little town, buying a pair of galoshes here, a comb there, pausing to talk with the local newspaper editor at another town. He handshook his way through a state in which only 25,000 Democrats voted in the primary, rewiring loyalties as he went, pleading, ‘Ah’m Estes Kefauver. Ah’m up here to ask for your he’p.’”

To that humble greeting, the candidate added in his populist message. “Kefauver was running against [Adlai] Stevenson, of Illinois, of Chicago, of the Cook County machine,” White wrote. “Everyone knew that. But Kefauver made it simple: ‘Don’t let those Chicago gangsters take our party away from us.’” Kefauver’s anti-boss feelings had only sharpened since they had taken the nomination away from him at the Chicago convention in 1952.

Although Stevenson had the support of the entire New Hampshire party establishment, his absentee campaign was no match for Kefauver’s personal touch. Kefauver won by a landslide, capturing 84 percent of the vote. “With that,” said White, “the dominance of the American attention by the New Hampshire primary began.”

After that, White followed Kefauver to Minnesota, where Stevenson again had the support of the state’s Democratic establishment, including Senator Hubert Humphrey and Governor Orville Freeman, while Kefauver’s lone elected backer in the state was Rep. Coya Knutson.

White admired “Kefauver’s great form in his folksy way. He stood in the snows of Minnesota as he had in New Hampshire and denounced Humphrey and Freeman as bosses, as he had denounced the Chicago gangsters bossing Stevenson.” And once again, Kefauver scored a stunning victory.

White was sitting in Kefauver’s hotel room that night, the two sharing a bottle of bourbon, when the result came down. Flush with victory, Kefauver told White, “When Ah get to the White House, you just come up to the gate, ring that bell, give your name, and Ah’m gonna let you in myself.”

White described how the twin shocks of New Hampshire and Minnesota drew Stevenson out onto the trail, where he did his best to copy Kefauver’s campaign style, though it didn’t come naturally to him. White also recounted the pivotal contests in Florida and California; Stevenson won narrowly in the first and by a landslide In the latter, effectively ending Kefauver’s campaign.

White pointed out that California was always going to be tough for Kefauver, as it was too large to effectively employ his person-to-person campaign strategy (particularly while ping-ponging back and forth to Florida, since the primaries were just a week apart). “Stevenson knew how to raise money better than Kefauver,” White said. “[I]n California, a media state, money buys media.” Kefauver couldn’t shake enough hands to overcome Stevenson’s edge in money and establishment support.

The Stevenson-Kefauver duel established the form for primary seasons to come. “The exercise of 1956 had then marked, though none of us knew it, a historic beginning – the beginning of the quadrennial coast-to-coast marathon,” White wrote. “The primary campaign trail still opens officially in New Hampshire in winter, and closes four months later, officially, in California.”

Having seen Kefauver up close, what were White’s impressions? Overall, he was impressed. Of all the unsuccessful candidates he ever met, he ranked Kefauver with Stevenson, Humphrey, and Nelson Rockefeller as “most qualified for the leadership denied him.”

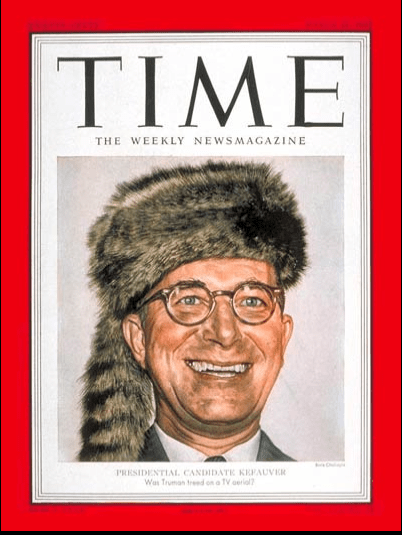

White noted that although Kefauver “affected the Southern populist style of primitive or ‘hick’… underneath the coonskin was a hard, educated mind. He could speak legalese as tightly as any Yale Law School graduate (which he was). When lubricated with bourbon, he could reach genuine eloquence… Beyond that he was sagacious and conscientious, a scholarly student of government[.]”

White also called him an “independent thinker” who “conducted some of the most important congressional investigations of his time,” and said that “[a] genuine profile in courage rose from his voting record in Congress; he had been on the short end of so many unpopular votes on the Hill.”

As an example, White cited Kefauver’s lone vote in 1954 against a Democratic-sponsored bill that would make Communist Party membership a crime, despite the fact that he was in the midst of a tough re-election race. (This would have been particularly meaningful to White, who had covered China as a reporter in the 1940s and 1950s. During the McCarthy era, White’s reporting connections to Communists brought him under suspicion and nearly torpedoed his career.)

“Kefauver’s solitary vote could only have sprung from conscience since it could only hurt him politically,” White wrote. “I asked him later why he had done so. ‘Well,’ replied Kefauver, ‘Ah figured the way that resolution was worded, you could put a man in jail just for what he was thinking in his haid.’”

White also considered Kefauver a trailblazer in other ways. “He was the first American projected to national political attention by television – in 1952, by the Kefauver hearings on organized crime,” he wrote.

More debatably, White states, “He was the first Southern candidate to venture north of the Mason-Dixon line since the Civil War, claim his due share of national attention, and earn the right to challenge for the presidency despite his Southern origin.” This is true only if you don’t count Woodrow Wilson, who was born in Virginia and grew up in Georgia before moving to New Jersey, where he was president of Princeton and governor before his election as President.

Naturally, I was pleased to see that White shared my high opinion of Kefauver. But I was even more pleased to see him credit Kefauver as “the godfather of the presidential primary system.”

If a reporter as respected as Teddy White could see that, then there’s hope that perhaps someday Kefauver will get the credit that he deserves. He was the first politician to gain national recognition through television, and he was the first one to seek the Presidential nomination from the people, instead of the bosses.

Leave a reply to I Want A Brave Man, I Want a Caveman: Kefauver Comes to Grants Pass – Estes Kefauver for President Cancel reply