The Presidential primary season has turned into something of an endless march. Every four years, would-be nominees start beating the bushes in Iowa and New Hampshire, now often beginning the year before the election itself. You know that it’s officially election season when an aspiring candidate just happens to find an excuse to show up in Manchester or Des Moines, shaking hands and giving speeches.

Not everyone is enchanted by Iowa’s and New Hampshire’s self-appointed first-in-the-nation status and the degree to which the results in those states often winnow the field dramatically before the other 48 states have a chance to weigh in. The Democratic Party in particular seems determined to evict these two small, rural, heavily white states from the front of the primary.

Defenders of the New Hampshire primary and Iowa caucus, on the other hand, point out that the states are well suited to retail politics. They’re both small enough to make that approach feasible, and their citizens take their roles in evaluating the candidates seriously. It’s a chance for voters to see the candidates up close and personal in a way the Presidential election process usually doesn’t allow.

Whenever you hear about a candidate vowing to visit each of Iowa’s 99 counties or tromping through the Granite State snow to greet voters in one small-town diner after another, that candidate is paying tribute to the retail-politics tradition in those states.

But where did that tradition come from? Why do candidates go through these rituals every quadrennium, temporarily treating the Presidential campaign like a run for school board or city council?

I’d argue that it was Estes Kefauver who created this tradition, and who established the model for the modern era of Presidential primary campaigning. But as usual, he rarely gets the credit that he deserves.

Giving the Voters a Voice

To be clear, Presidential primaries existed before Kefauver’s first run for the Presidency in 1952. States began holding primaries for President in the early 1900s, as part of the Progressive Era reforms to get the people more directly involved in our election process. (The 17th Amendment, which mandated the election of Senators by popular vote, also came out of this era.)

But the primaries initially weren’t a major part of the selection process for Presidential candidates. Relatively few states held them. In some that did hold them, the primaries were simply popularity contests that didn’t affect the selection of delegates. In others, the voters could select the delegates, but those delegates weren’t pledged to vote for any particular candidate. Often, the only candidate in a given state primary would be a “favorite son,” a powerful politician in that state who might not even actually be interested in the Presidency, but wanted to have control of the state’s delegation.

The national convention was still where the action was, where the parties actually decided who their nominees would be. Participation in the primaries was essentially optional. A candidate could choose to run in one or more primaries to show his interest in the Presidency and to control a block of delegates at the convention. But it was impossible to win enough delegates for the nomination through the primaries, and several successful nominees in this era didn’t even bother to participate at all.

Even if a candidate did choose to run in a given state’s primary, he might not even bother to show up there. He might rely on friendly elected officials and party bosses in that state to make the case for him. Even if the candidate did show up to make a speech or two, it wasn’t the glad-handing, one-on-one campaigning that we associate with Iowa and New Hampshire today.

Kefauver changed all that, for two important reasons. First, it was simply the way he was wired as a candidate. But also, it was because he had to. He knew that no one was going to hand him the nomination.

Leaving His Mark on the Granite State – and Taking Down a President

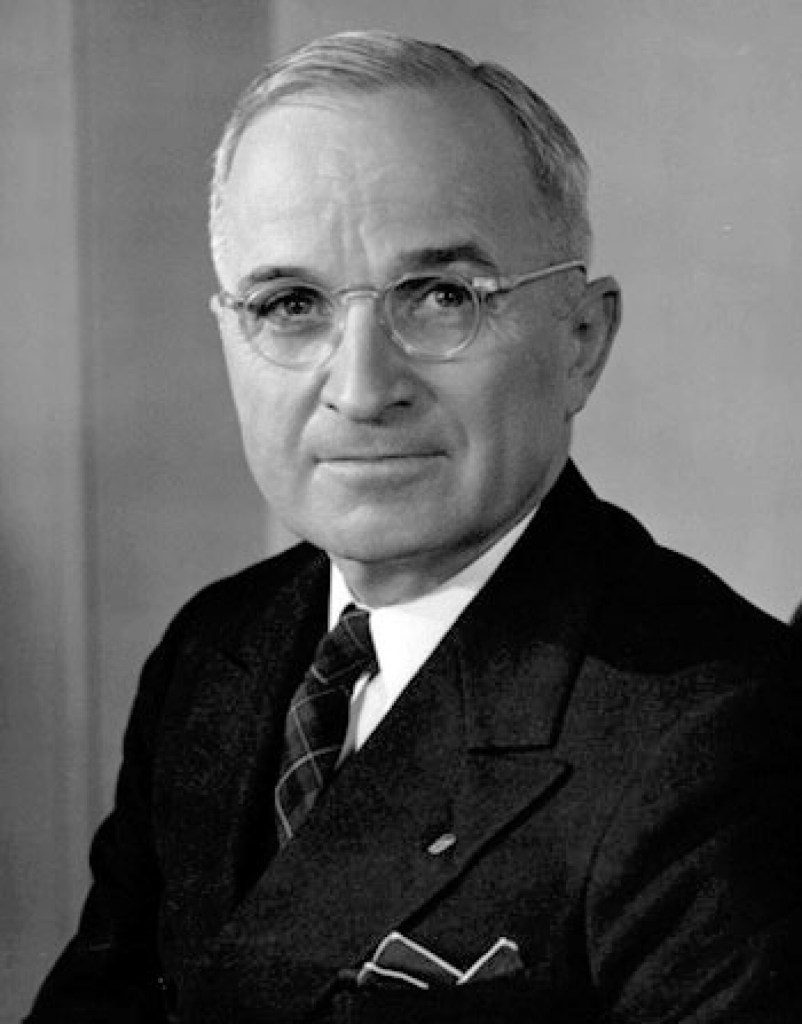

Heading into 1952, Harry Truman faced dismal approval ratings, beset by numerous scandals and facing a public weary of 20 years of Democratic rule. Despite this, Truman refused to rule out running for re-election. He wanted to make the decision on his own timetable; if he chose not to run, he wanted to be able to choose his successor.

Kefauver wasn’t going to wait until Truman made up his mind, and he knew he couldn’t count on the President to anoint him as the designated successor (even if he didn’t yet realized how bitterly Truman opposed him).

– Harry Truman, probably

So instead, he decided to take his case to the people, starting with the first available primary: New Hampshire. Unlike other politicians, who showed up with an army of staffers and a rigid agenda of speeches, Kefauver arrived accompanied only by his wife Nancy, and they just kind of… wandered around the state, popping into stores and shipyards and ski lodges, shaking hands with whomever they met.

Kefauver’s gambit was unheard of, so much so that it was hard for reporters to know what to make of it at first. The Portsmouth Herald described it as “a straight man-on-the-street approach – with ordinary men on the street,” and added that there was “an atmosphere of both surprise and bafflement in town prior to Senator Kefauver’s somewhat sudden arrival in town.”

But while the approach confused the political bosses and the press, it proved popular, as voters turned out in droves to shake Kefauver’s hand and talk to him. This put Truman in a bind. Should he skip the primary and risk Kefauver racking up publicity with an uncontested win, or fight it out and risk a potentially fatal loss?

One of Truman’s supporters entered his name into the primary without consulting him first. Truman responded to this by denouncing the primaries as a “load of eyewash” and demanding that his name be removed. This statement generated considerable backlash, both from the public and from his campaign advisers, who felt it would be better to battle it out in New Hampshire and crush the Kefauver boom before it could get started.

As a result, five days later, Truman wrote to the New Hampshire Secretary of State asking that his name be left on the ballot. “I have long favored a national presidential primary so that the voters could really choose their own candidates,” he claimed, inaccurately. “However, I thought it would be better for my name not to appear on any ballot… until I am ready to make an announcement as to whether I shall seek reelection.”

Truman probably should have stuck with his initial instinct. Kefauver posted a shocking victory in New Hampshire, effectively ending the incumbent’s re-election hopes. (He formally withdrew from the race 18 days later.)

“Hey, Harry, can you read that?”

Kefauver proceeded to win virtually every primary he entered, rolling up over 3 million votes. Unfortunately, those primaries meant nothing to the party’s power brokers, who had little trouble snubbing Kefauver in favor of Adlai Stevenson, who had not run in the primaries and had to be talked into accepting a draft at the convention.

At the time, the fact that the Democrats snubbed the runaway winner of the primaries was not considered scandalous. But both Kefauver and his supporters took the defeat very hard. The following year, Kefauver proposed a Constitutional amendment mandating a national primary system for the Presidency (a suggestion that was quickly shot down by his colleagues).

Lighting the Fuse of a Revolution

Even though his amendment went nowhere, Kefauver’s run through the primaries in ’52 lit a fuse that would ultimately lead to a sea change in the nomination process. And from that point forward, it would be much harder for the Democrats to treat the primaries as meaningless.

In 1956, Stevenson realized that he had to enter the primaries if he wanted the nomination a second time, and he ultimately had to copy Kefauver’s handshaking, man-on-the-street campaign tactics in order to win. And when Stevenson threw his choice of running mate to the convention, Kefauver was able to use the popularity he’d gained through his two runs to capture the Vice Presidential nomination.

In 1960, John F. Kennedy used the primaries strategically to prove his electability to the party power brokers, and to show that America was ready to elect a Catholic as President. His victories over Hubert Humphrey in the Wisconsin and West Virginia primaries helped give him critical momentum that allowed him to clinch the nomination at the convention.

The party bosses reasserted themselves in 1968, handing the nomination to Vice President Humphrey despite his having skipped the primaries. But this time, the fuse that Kefauver had lit 16 years earlier finally reached the dynamite. Democratic voters demanded a greater say in choosing their nominees. The party responded by setting up the McGovern-Fraser Commission, which sparked major changes in the process, dramatically reducing the power of party bosses in choosing nominees and giving more power to rank-and-file voters.

The next two Democratic nominees, George McGovern in 1972 and Jimmy Carter in 1976, were able to capture the nomination by rolling up wins in the primaries, and the bosses – who were indifferent if not outright hostile – couldn’t stop it.

At this point, the idea that the voters get to choose the nominees via the primaries is so well established that when the Democrats floated the idea of denying Bernie Sanders the nomination in 2016 using the votes of so-called superdelegates, the voters reacted with fury. (That same year, Donald Trump’s capturing of the Republican nomination showed just how much the pendulum had swung away from the party leaders.)

So Kefauver deserves credit for starting the momentum toward putting nominations in the hands of the voters. But he also deserves credit for bringing the retail-politics approach to Presidential campaigns that still prevails in New Hampshire (and Iowa, which moved its caucus to the front of the calendar in the 1970s after the McGovern-Fraser reforms).

You don’t just have to take my word for it, either. In December 1967, The Atlantic ran an article on the history of the New Hampshire primary. The article quoted a long-time Granite State politician, Republican Senator Norris Cotton, who acknowledged the way that Kefauver changed the way politicians campaigned in the state – a change that Cotton didn’t like.

“Cotton blamed a Democrat, the outlander Kefauver, for starting the practice of rambling all over the state, grabbing hands, patting children, and turning the primary into a carnival,” the article stated.

I believe Kefauver would have been pleased to see the outcome of the changes he started, if he’d lived long enough to see them. He may never had fulfilled his Presidential ambitions, but he sparked changes to the nominating process that outlived him – whether he gets credit for it or not.

Leave a comment