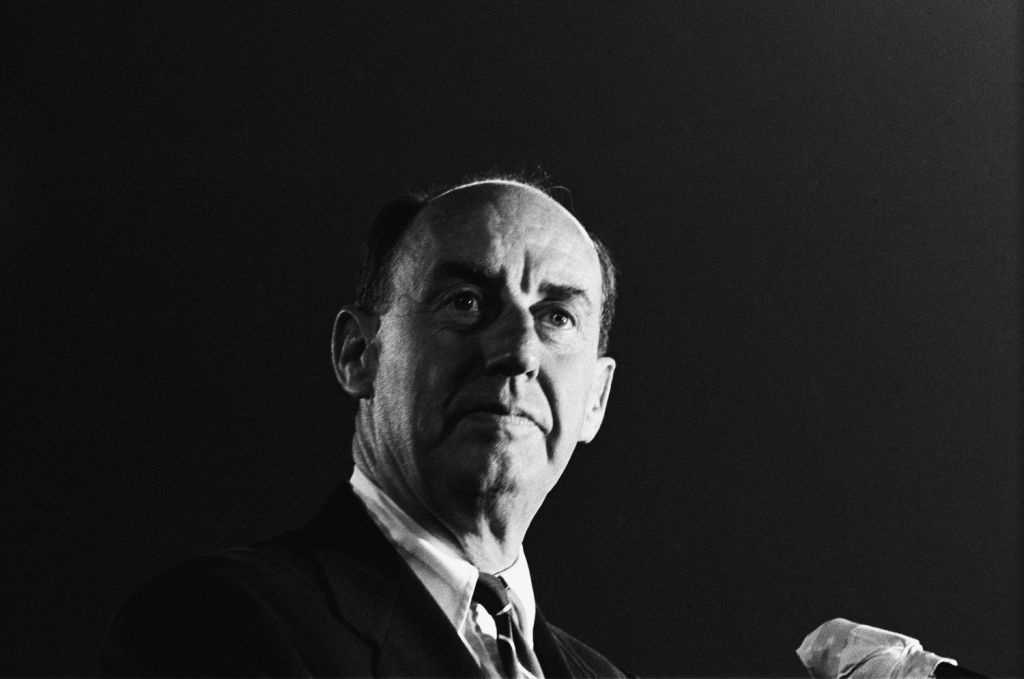

Adlai Stevenson occupies a peculiar place in American history. Despite a thin record of political achievement, he received not one, but two shots at the Presidency in 1952 and 1956. In those campaigns, he earned a reputation as one of the most admired losing candidates of all time.

Stevenson’s eloquent speeches, witty remarks, and intellectual reputation were fondly remembered by political reporters and historians alike. When he lost, his graceful concessions only burnished his reputation as a classy, dignified statesman. For a long time, Democrats of a certain age tended to sigh wistfully and ask, “Why can’t we find candidates like Adlai anymore?”

I used to feel that way about him. I don’t any longer.

Don’t get me wrong. Stevenson was a good and decent man, smart and witty and eloquent and all that. But the more I’ve studied Kefauver, the more I’ve realized that Stevenson wasn’t a very good Presidential candidate. And the worship of Stevenson and his approach to politics wound up crippling the Democrats for a generation or longer.

It’s a bit strange that Stevenson was so fondly remembered. He was a rich patrician who had almost all his political opportunities handed to him on a silver platter. He acted as though politics was beneath him, and that the gravest sin a politician could commit was to desire the office he was running for. When he campaigned, he struggled to conceal his disdain for shaking hands, posing for photographs, and the other realities of life as a candidate.

Democrats, enchanted by his soaring speeches and clever repartee, ignored the fact that he was at best lukewarm on the issues that had been their bread-and-butter since FDR. And they seemed smugly content that their candidate would win an IQ test or a public-speaking competition, even as Ike cleaned up in the election.

This does not sound like someone that Americans tend to regard fondly. Honestly, it sounds like the sort of person Americans tend to resent. And yet, journalist Bill Wirtz once said, “If the Electoral College ever gave an honorary degree, it ought to go to Adlai Stevenson.” What gives?

Let me walk you through Stevenson’s charmed career, and you can make your own judgments.

An Engraved Invitation to Politics

Adlai Stevenson got into electoral politics because he was bored. That’s not my opinion; it’s his. He had held low-level positions in FDR’s administrations while also establishing a career as a wealthy Chicago lawyer. But it wasn’t enough.

On his 47th birthday, he wrote in his journal that he was “still restless, dissatisfied with myself. What’s the matter? Have everything. Wife, kids, money, success – but not in the law profession. Too much ambition for public recognition… how can I reconcile life in Chicago as a lawyer with consuming interest in foreign affairs – public affairs and desire for recognition and position in that field?”

Meanwhile, the Chicago Democratic machine had a problem. Their habit of nominating crooks and hacks for public office was wearing thin with an increasingly discerning public, and they needed some highbrow folks to class up their image.

One of their strategists, Jacob Arvey, met Stevenson and found him wealthy, classy, polished… just the ticket.

There was just one problem: the machine wanted him to run for Governor, but Stevenson wanted to be a Senator. He was interested in foreign affairs, not in the state-level issues. But the machine already had a Senate candidate in Paul Douglas; they wouldn’t run Douglas for Governor because they felt he was too independent-minded. Stevenson was considered more malleable.

Stevenson considered walking away from the whole deal, but his friend Dutch Smith warned him: “If you say no whey they need you, they won’t take you when they don’t need you.” Stevenson reluctantly agreed to run for Governor.

He faced incumbent Dwight Green, a former prosecutor who had been elected as a reformer and machine opponent. But Green’s reputation suffered a hit in March 1947 when a mine explosion in Centralia killed 111 people. Although the explosion was an accident, the subsequent investigation found that state mine inspectors had been lax and Green had ignored a letter from the miners begging him to do something about the conditions in the Centralia mine.

This allowed Stevenson to attack Green as corrupt and heartless, and he scored a surprising upset win. (Stevenson’s 1956 Presidential campaign brochure described the situation this way: “In 1948, the Democrats needed someone to overthrow the corrupt Administration of Governor Dwight Green.” “Overthrow” was a weird word choice; it made Illinois sound like a banana republic.)

Stevenson pursued a reform agenda as Governor, with mixed success. But toward the end of his term, another promotion opportunity was waiting right around the corner!

How to Succeed in Politics Without Really Trying

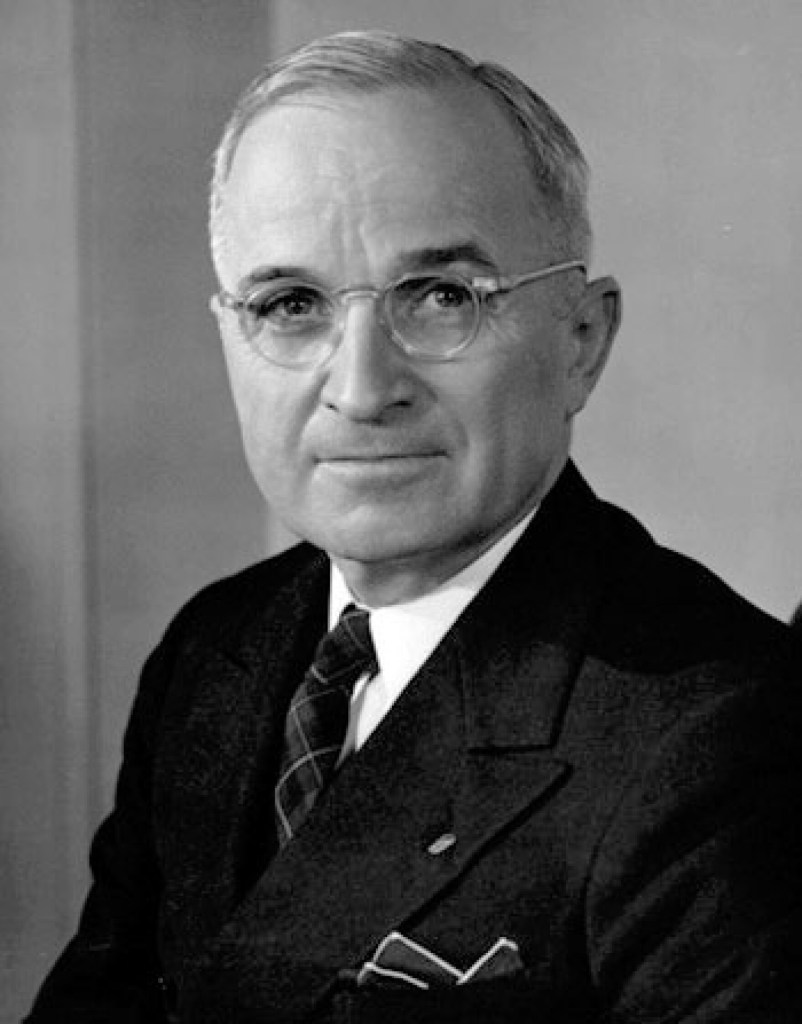

In 1952, President Truman was looking for someone – anyone – who could stop Estes Kefauver from winning the Democratic Presidential nomination. Kefauver had already annoyed Truman with his organized crime probe, which had revealed far too much Democratic corruption – including in Kansas City, where Truman had come to power. The Senator from Tennessee only compounded the felony by beating Truman in the New Hampshire primary and forcing him to abandon his re-election bid.

Truman quickly turned his eyes to Stevenson; he admired the Governor’s intelligence and clean reputation. But Stevenson said no, multiple times, to the point of really pissing off Truman.

It wasn’t until the convention when the Governor, after vigorous arm-twisting by virtually every power broker in the party, finally agreed to accept a draft. He proceeded to make a keynote speech so eloquent that it made the delegates swoon, and they chose him on the third ballot.

Imagine, if you will, what it must have felt like to be Estes Kefauver at that convention. You’d spent the spring and summer crisscrossing the country, giving hundreds of speeches and shaking thousands of hands, making the case why you deserved to be the nominee. You won almost every primary that you entered. But when you got to the convention, the party threw you overboard in favor of a guy who had to be dragged kicking and screaming into accepting the nomination.

Stevenson proceeded to run a general election campaign that could best be described as feeble. As David Halberstam put it in The Fifties, “As [Stevenson] had been nominated as an independent, he came to believe himself one, implying that there was no need to court the various interest groups and blocs that made up the Democratic party.”

Basically, he acted as though he was doing the country a favor by running, an approach that rarely charms voters. His staffers had to pressure him to adopt Democratic positions and campaign in a partisan fashion. He scoffed at the idea of using a Madison Avenue agency to help craft his ads and TV appearances, ceding a huge advantage to Eisenhower, whose spots hammered simple themes and slogans relentlessly. “How can you talk seriously about issues with one-minutes spots!” Stevenson complained, missing the point entirely.

Stevenson’s high-minded campaign and his refusal to stoop to TV-ready slogans or McCarthy-style demagogic attacks earned him the admiration of America’s intelligentsia, but it won Eisenhower the votes of most Americans. Ike won the popular vote by over 10% and racked up 442 electoral votes. Stevenson couldn’t even carry the staunchly Democratic South, losing states like Tennessee, Texas, Florida, and Virginia.

After the election, Stevenson was out of a job, since he’d bailed on a second term as Governor to run for President. (His Lieutenant Governor, Sherwood Dixon, ran instead and was clobbered.) He went back to his law practice, but continued to make speeches on behalf of Democratic candidates, helping them win back the Senate in 1954 after having lost it two years earlier.

Come 1956, Stevenson would receive credit for supporting down-ballot Democrats. Meanwhile, Kefauver campaigned just as faithfully on behalf of his fellow Dems, but all it got him was scorn for supposedly ignoring his Senate duties. Since Stevenson was wealthy enough not to need steady work, his campaigning was met with gratitude.

1956: Stevenson Actually Campaigns for a Change

Although Stevenson’s campaign brochure called him “the obvious choice of his Party in 1956,” it was no cakewalk. He actually had to run for it, entering the primaries against Kefauver. And Stevenson – despite his much-documented disdain for campaigning – hit the trail vigorously.

Ultimately, the race came down to primaries in Florida and California, just a few days apart. This caused problems for both candidates, both for logistical reasons (they both had to ping-pong from coast to coast for weeks) and ideological ones. Civil rights were a key issue that year, and both candidates had to find a position simultaneously liberal enough for California and conservative enough for Florida, an impossible task.

Both candidates’ civil rights stances wound up being similar; if anything, Kefauver may have been slightly more progressive on the issue. But as a native Southerner, he paid a heavier price it in Florida than Stevenson.

At that point in the race – seeing a photo finish in Florida, knowing Stevenson had a huge edge in both money and institutional support in California, doubtless jet-lagged from the cross-country travel – Kefauver cracked. Having scrupulously avoided criticizing his rival throughout primary season, he finally launched a very mild attack, accusing Stevenson of vetoing a pension for elderly and blind residents as Governor of Illinois.

The political press reacted as though Kefauver had gone full Joe McCarthy. “On Wednesday of the final week of the campaign [Kefauver] had made a decision sure to affect his whole political future,” sniffed Stewart Alsop. “His decision was to play it rough.” Thomas L. Stokes agreed, slamming Kefauver for his “desperate but carefully premeditated gamble of slashing at” Stevenson. Meanwhile, Stevenson had for weeks been attacking Kefauver for absenteeism from the Senate and hinting that Kefauver’s Senate colleagues all hated him, but these same columnists seemed unbothered by that.

Stevenson won big in California, and went on to win the nomination, but threw open the selection of his running mate to the convention. The convention picked Kefauver; while this was not Stevenson’s preferred choice, he reacted with grace.

He delegated to Kefauver the role of attack dog against the Eisenhower administration and sent him to all the flyover states that Stevenson wasn’t interested in visiting. He begrudgingly agreed to accept Madison Avenue’s help in crafting TV spots to make him appear relatable to the average voter; unfortunately, the “Man from Libertyville” ads weren’t terribly successful (see my piece on the ad where he tried to convince America that he understood farmers and their problems). None of this was enough to stave off another crushing defeat in November.

A Bad Example for Future Dems

Why bring up all of this now? I’ll grant that some of it is personal. Ike has been retconned as an electoral juggernaut in the popular imagination, but I believe that if the Democrats had chosen their most popular candidate – Kefauver – in 1952, he would have run a stronger race, and possibly even won.

But there’s a larger point here too. The Cult of Stevenson represents some of the worst tendencies of the Democratic Party.

The elitist party that believes intelligence and lofty rhetoric makes you morally superior, even as you get your clock cleaned in election after election. The party that acts as though politics is a fundamentally dirty business, and that it’s somehow beneath them. The party that values pretty speeches over connecting with average voters, and then can’t understand why those voters keep defecting to the other side.

Whatever his shortcomings, Kefauver didn’t make those mistakes, and it’s why voters – you know, the people who actually decide elections – loved him. In general, the Democrats would be better off if they tried to be less like Stevenson and more like Kefauver.

Leave a reply to Campaign 1956: What Might Have Been – Estes Kefauver for President Cancel reply