Earlier this week, I read an article in Politico about Elon Musk’s endorsement of Donald Trump. The article drew parallels between Musk’s bromance with Trump and an earlier incident from the 1950s, when Henry Luce – publisher of Time and Life magazines – went gaga over Dwight Eisenhower for President.

Naturally, given my historical interests, I was much more interested in the Luce-Trump part of the story. Luce had a relationship of mutual hostility with the administrations of Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman. So when Eisenhower entered the political arena – a Republican and an internationalist, both very much in tune with Luce’s views – the publisher was all in.

The degree to which Luce went in the tank for Eisenhower seems shocking today, and would have been shocking even at the time. He lent several of his own staffers to Eisenhower’s campaign, and some of them went to work in the administration – including Luce’s wife, Claire Boothe Luce, who served as Ike’s ambassador to Italy.

He directed both Time and Life to write pro-Eisenhower articles; when some of his staffers balked – calling the magazines “Eisenhower’s mouthpiece” – Luce responded, “I am your boss. I guess that means I can fire any of you.” The coverage that Time provided of Ike was so flattering that his campaign manager, Henry Cabot Lodge, started handing out copies.

As President, Eisenhower received the same level of worshipful coverage. Luce seemed indifferent to the fact that the pro-Ike and pro-Republican slant of his magazines was damaging their reputation with Democratic readers.

I found this story illuminating, but I didn’t find it surprising. It was illuminating because it explained something I’d long observed: Time’s history of negative and hostile coverage of Estes Kefauver.

Mind you, it wasn’t always that way. Time wrote favorably about Kefauver during his initial campaign for the Senate in 1948, portraying him as David slaying the Goliath of Boss Crump’s Memphis machine. In 1950, the magazine named him one of the “Senate’s Most Valuable Ten,” praising his opposition to the poll tax and his support of political reform. Time also provided generally positive coverage to his hearings on organized crime in 1950 and 1951.

But as soon as Kefauver started running for President in 1952 – thereby putting himself in the path of Luce’s beloved Eisenhower – Time’s coverage of him turned sharply negative. From that point forward, the magazine went out of its way to portray Kefauver as dumb, vain, humorless, and publicity-crazed.

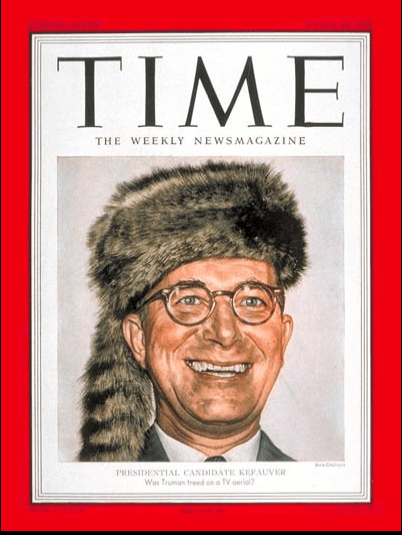

Time featured Kefauver on the cover of its March 24, 1952 issue after his stunning upset of President Truman in the New Hampshire primary. The article itself, however, was practically a hit piece.

They called up “one of the dullest, most fumbling speakers in the Senate” and mocked his platform as vague and meaningless. They dismissed his personal touch with voters, making them feel heard and special, as a “confession of mental bankruptcy.” Even the crime investigation – which the magazine had praised a year before – was now written off as a rehash of “old stuff contributed by friendly cops and newspapermen,” and it was chief counsel Rudolph Halley who provided the “investigative initiative.”

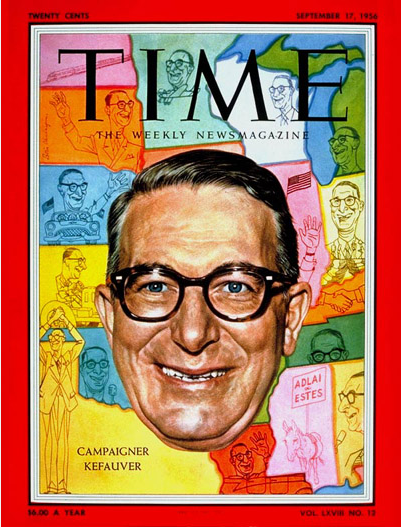

Kefauver didn’t get any kinder reviews from Time during his second Presidential run, nor when he was chosen as Adlai Stevenson’s running mate. He once again made the cover on September 17, 1956, but again, the accompanying article was unkind. Kefauver was said to be “almost inarticulate in expressing his policies. When asked precisely what he stands for, he is likely to hesitate, ponder painfully, and finally come up with some such phrase as ‘a place in the sun for the farmer,’ or ‘the best interests of the plain people of this nation,’ or ‘an even break for the average man.’”

Time also (as in 1952) made a point of stating that Kefauver’s family was relatively well-off, implying that his claim to be a friend of the common man was a lie. The article repeated the common charge that Kefauver was “the rankest sort of opportunist, who will do anything to grab a headline.” (Whenever Time wanted to smear Kefauver, they frequently relied on the anonymous opinions of fellow Senators.)

Even when Kefauver died in August 1963, Time couldn’t let go of the obnoxious sneering tone they frequently used when talking about him. In the first paragraph of the magazine’s memorial piece, they called him “a glad-hander who never managed to look really glad,” said that his campaigning “achieved a kind of glum sincerity,” and noted that several fellow Senators “insisted that there was a vacuum in the space between his ears.” The nicest thing they could think to call him was “a great vote-getter with a vast store of plodding energy and a vaulting ambition,” which isn’t particularly a compliment when you think about it.”

When I first read these articles, I assumed that Time’s hostility to Kefauver was driven by the low regard in which many of his fellow Senators held him. I figured that their reporters reflected the opinion of the Washington “smart set,” who swooned over Adlai and JFK and dismissed Kefauver as a clown.

But now that I know about Luce’s adoration of Eisenhower, the picture looks quite different. Kefauver was one of the few Democratic politicians who would have been popular enough to give Ike a real race. As a result, Luce likely directed his writers to depict Kefauver in an unflattering light.

Who knows how the 1952 election might have gone if one of America’s most popular news magazines hadn’t gone out of its way to boost Eisenhower and tear down Kefauver? It’s a fascinating hypothetical, and one that reminds us of what can occur when a powerful man with a big megaphone takes sides in an election.

Leave a reply to On, Wisconsin: Kefauver’s Campaign Magic at Work – Estes Kefauver for President Cancel reply