Estes Kefauver’s televised investigation into organized crime spawned a wave of films capitalizing on the public’s sudden interest. Some of them featured speaking appearances from the Senator himself. I’ve gone over some of those in the past, and will cover others in the future.

But the organized crime probe wasn’t the only Kefauver investigation to capture the interest of Hollywood. The juvenile delinquency hearings also spawned at least one picture. Sadly, it wasn’t a very good one.

The mid-1950s saw a spate of films dramatizing juvenile delinquency, keying off of nationwide anxiety about the subject. “Blackboard Jungle” and “Rebel Without a Cause” are perhaps the most famous of these pictures.

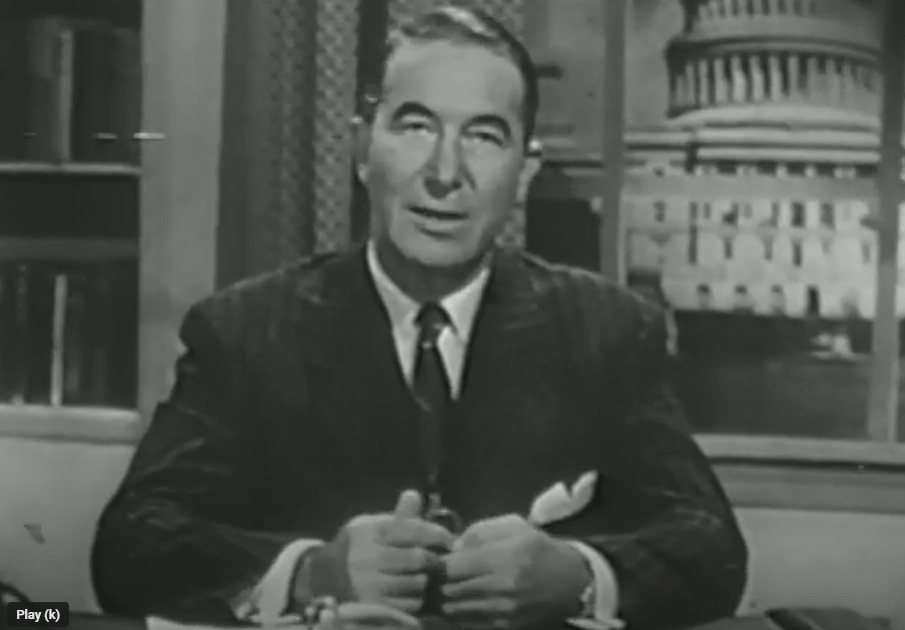

Today’s film – “Mad at the World” – is a less-remembered entry in this genre, and the only one to include Kefauver. As in the crime film “The Enforcer,” the Senator has a spoken-word prologue, tying his investigation to the movie.

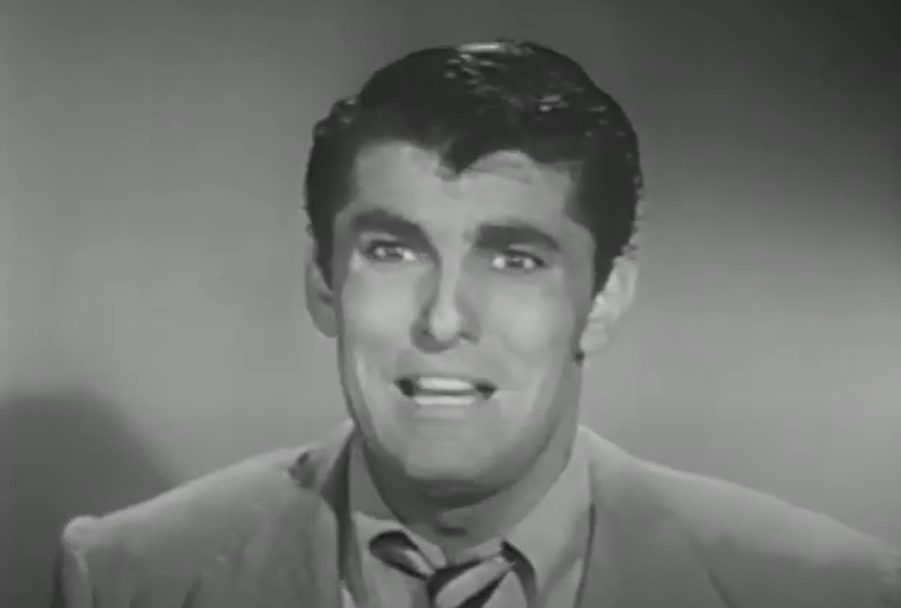

We begin with Kefauver in his Senate office; he tells the audience that they’re about to see a film about juvenile delinquency, which is the “tragic concern” of his Senate committee. He assures the public that his committee is “looking hard for the answers, and we think we’ve found some of them.” He doesn’t mention what those are, however.

He says that juvenile delinquency “sets up an ugly chain reaction: grown-ups, especially those innocent victims of youthful outrages, become angry too. Yes, anger breeds anger, until finally it sweeps over all age groups.” This seems like an odd framing– but once I saw the movie, it became clear why the filmmakers insisted on this point.

Kefauver closes by introducing “the story of how one police department in a great American city fought to bring this destructive human fire under control.” This implies that the movie was based on a true story, which it was not. However, producer Collier Young and director Harry Essex researched for the film by interviewing juvenile delinquents in LA jails.

The film itself opens with establishing shots of Chicago, where the action takes place, accompanied by a voiceover from Detective Tom Lynn (played by Frank Lovejoy), who describes his love for the city. He acknowledges there are problems too – particularly the slums, with “too many people crowded together too close, the price of growing too fast.” He says this is bad for kids, who wind up taking to the streets because they “need room to blow off steam.”

Detective Tom describes the struggle against juvenile delinquency as “a new kind of war for all police officers… a war in which we don’t want to kill the enemy, but we want to help and understand, if only they’ll let us.” (Hold onto that thought.)

We then meet a group of delinquents, led by Jamie Ellison (Paul Dubov), as they surround an unsuspecting adult and beat him senseless for no apparent reason.

The victim comes to the police station, where Detective Tom shows him holding cells full of delinquents (played by real-life parolees from the LA jail).

The detective cites an extremely dubious-sounding statistic: “For every adult who breaks the law, there are seven kids who commit a crime.” He claims this stat came from the FBI – the same group that was still pretending the American Mafia wasn’t a thing at that time.

The next day, Jamie and his gang are out on the streets, and they’re bored. They “borrow” a car from a nearby garage, stop by the liquor store, and they’re off for a night of malevolent fun.

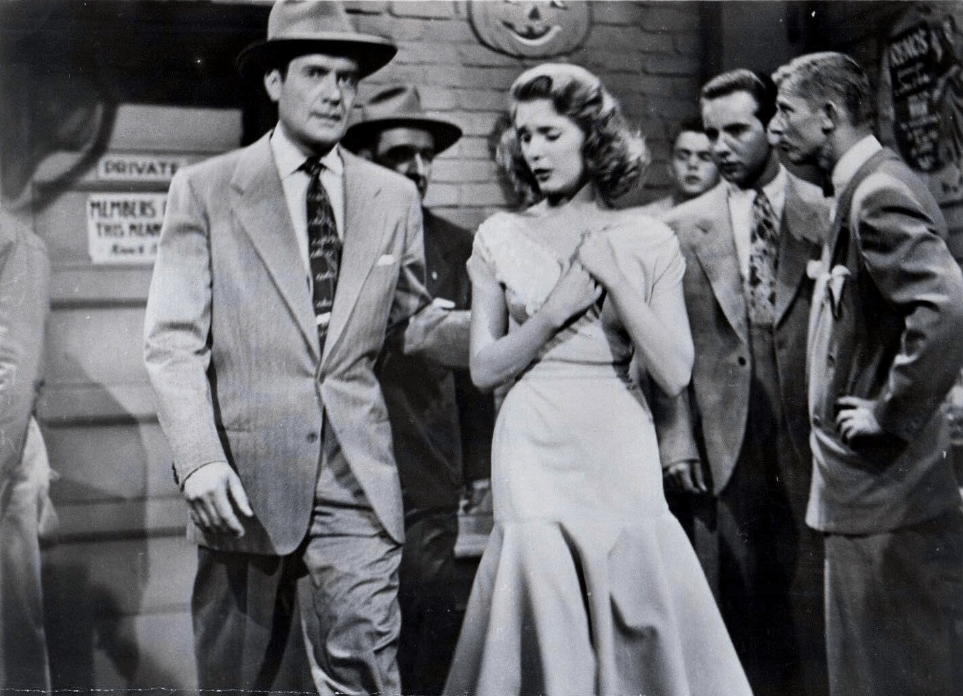

They soon encounter Sam and Anne Bennett (Keefe Brassele and Cathy O’Donnell) holding their baby Johnny and leaving their neighbors’ house. This vision of domestic bliss pisses off Jamie – “What are they so happy about?” he asks – and he chucks his whiskey bottle out the window at them. The bottle somehow shatters on impact, causing baby Johnny to be badly hurt.

The cops start shaking down the neighborhood where they suspect the delinquents live, to no avail. Distraught dad Sam, frustrated by the pace of the investigation, threatens to take matters into his own hands, but Detective Tom warns him off.

The police finally get a lead: they find the car that Jamie’s gang used. They pick up the owner, Willie Hanson (a young Aaron Spelling). Willie insists that he was home sick at the time of the incident; Detective Tom goes over to shantytown, where Willie’s parents back up his story.

Detective Tom then visits Willie’s social worker, Miss Lovett (Maidie Norman) for a set-piece discussion about the causes of juvenile delinquency. Neither of them really has any solid theories, although they both agree that poor parenting is a key cause. Miss Lovett narrows this a bit further when she recalls “a choice piece of corn I picked up at college: Save a boy, and you save a man. Save a little girl, and you save a whole family.” (This seems to ignore the role that alcoholic and/or abusive fathers can play in destabilizing families, but I digress.)

The cops let Willie go due to a lack of evidence. When they tell Sam this, he’s furious. He storms out and attacks poor Willie with a tire iron. Fortunately, Detective Tom breaks things up. He then punches Sam in the jaw and warns him, “Get out of here before I throw the book at you!”

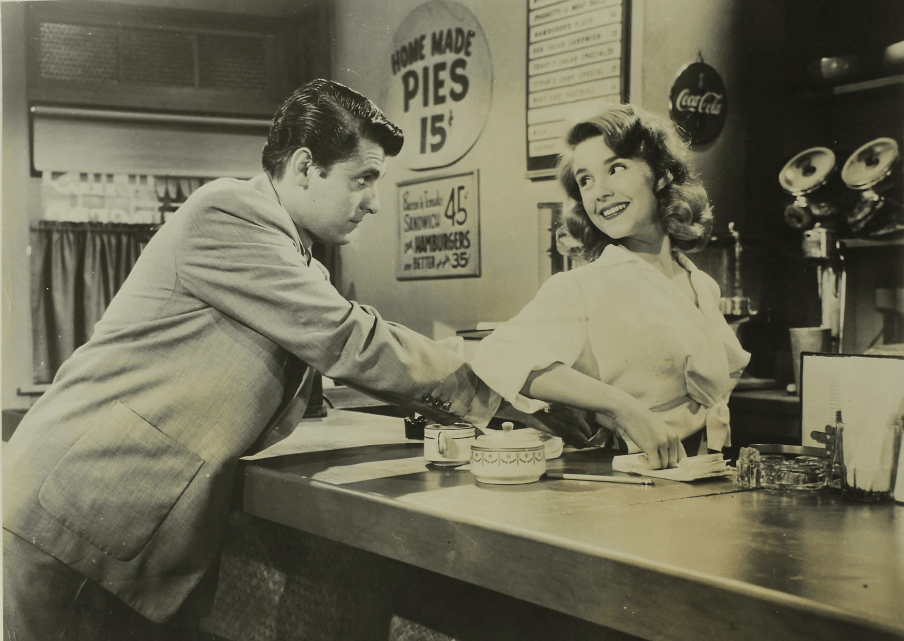

Sam’s lost it by this time, however, and he abandons his grieving wife to hang out in the slums and look for the delinquents himself. Using the alias “Bill Holland,” he finds their social club and spots Jamie’s girlfriend, Tess (Karen Sharpe), on her way to work at the diner next door.

When “Bill” enters the diner asking about a place to stay, Tess falls for him on sight.

She tells him there’s a vacant room in her boardinghouse, and they arrange a “date” at a local jazz club. I put “date” in quotes because “Bill” spends the whole night ignoring Tess and scanning the crowd, looking for the kids who did him wrong.

“Bill” displays an utterly comical lack of interest in Tess throughout, despite her repeated attempts to throw herself at him. She notices his disinterest and calls him out several times; for some reason, though, it doesn’t put her off, which is… interesting.

Meanwhile, Detective Tom goes to see poor Anne, who is frantic over her child’s fate and her husband’s disappearance. The gallant detective suggests that perhaps it’s Anne’s fault that Sam left, because she’s all mopey and dressed in her bathrobe. He reveals that he lost his son at a young age, and that he and his wife pulled through by sticking together. Inspired, Anne puts on a pretty dress and a brave face.

And Sam does come home! But he’s not there to comfort his wife; he’s looking for his gun. He yells at Anne for getting “prettied up” while their son’s life hangs in the balance. He then gets a call from the hospital, and learns that Johnny is dead. He shoves Anne aside and storms off, slugging Detective Tom on the way out.

Detective Tom goes back to the station and orders a public bulletin describing Sam and asking for his whereabouts, so Tom can take him into protective custody. (Matt correctly points out that they should be arresting him for assault instead.)

The police lab techs finally reconstruct the shattered whiskey bottle and lift some fingerprints. They identify one of Jamie’s cohorts, Pete, and drag him in for questioning. Pete initially dummies up, but Anne (who for some reason is allowed to be there) begs him to talk for the sake of poor dead Johnny. This reaches Pete, who gives up the names of his accomplices, saying that they’re heading to a dance at the social club.

Guess who else is at the dance? Tess and “Bill”! His wall of disinterest is thicker than ever. Tess drags him into a backroom and kisses him, and he pushes her away. This finally causes her to snap, and “Bill’s” explanation makes things worse. “Some things you can’t explain, Tess!” he says. “Like the way a person feels inside, deep inside. I… wish I could love you, take care of you… but I can’t.” (This sounds to a modern audience like “Bill” is trying to tell Tess he’s gay, but remember this is 1955.)

“Don’t you understand, Tess?” he says. She very much does not, and stalks off into the arms of Jamie, where they engage in some truly hilarious revenge-dancing. Unfazed, “Bill” then invites Jamie and his cohorts to leave the dance and head to the college to crash a frat party.

Just as they’re leaving, though, the garage attendant (who caught the police bulletin) warns Jamie that “Bill” is actually Sam, the vigilante father. Jamie correctly deduces that Sam is luring them into a trap, so he knocks Sam out and orders his buddies to drive them to the lumberyard, where he can dispose of Sam’s body in the incinerator.

Jamie and company depart just before the cops crash the party. Detective Tom harshly questions Tess, who reluctantly tells the cops of their (alleged) plan to crash the frat party.

The police head off for a futile sweep of the campus. Fortunately, another cop sees Jamie’s car turning off to the lumberyard, and phones it in.

Jamie tries to get his friends to grab Sam’s body, but one of them – Marty – balks. Jamie calls him a “dirty little yellow-bellied Polack” and shoots him. Meanwhile, Sam wakes up and starts fighting the remaining two delinquents. He knocks out one, then turns to Jamie. They wind up having a dramatic fistfight on the catwalk, and Jamie falls to the ground. Sam is about to shoot him when Detective Tom shows up and orders him to stop.

“I’m not trying to give you answers, Sam,” says Detective Tom. “I don’t have any… Someday, somebody will come along with a better answer. But until then, we’ve got to understand.”

Sam lowers his gun, but it’s too late for Jamie, who’s dying from his fall. Detective Tom asks him, “Why are you a killer for kicks? What made you mad at the world?” Jamie responds with a rambling speech about how nobody gives you something for nothing, and you have to take what you want, or someone else will. “You gotta find your kicks, or go without ‘em,” he says, and then dies.

At this moment, Anne shows up and embraces her bloodied husband. Detective Tom and Matt light a cigarette and walk away. Happy ending!

Seriously, this is a terrible movie. There’s a reason you probably haven’t heard of any of the actors involved. Lovejoy makes a convincing Joe Friday-esque deadpan detective, but the rest are all stock characters or worse. Brassele is particularly terrible as Sam; he runs the gamut of emotions, none of them convincing.

Even worse is the movie’s muddled message. Detective Tom, the film’s theoretical conscience, keeps preaching about the importance of understanding these troubled juveniles, but the kids mostly come off as idiots or remorseless thugs. All the adults repeatedly admit that they don’t have any good answers for why kids turn delinquent (a problem that also plagued Kefauver’s committee).

Also, why is Sam – who assaulted two innocent people, including a police officer, and is at least liable for manslaughter in Jamie’s case – allowed to go free, while the kids all wind up in custody or dead? It doesn’t exactly seem like an advertisement against vigilante justice.

If you must, you can watch the movie below. At least it’s short – little more than an hour. Kefauver’s speech is right at the beginning.

Leave a comment