One of the defining aspects of Estes Kefauver’s career was his failed runs for President in 1952 and 1956. Whether you attribute those losses to the machinations of Democratic party bosses, his shortcomings as a candidate, or the cruel whims of fate, there’s no question that Kefauver would be better remembered today if he had captured the nomination (even more so if he’d made it to the White House).

But Kefauver wasn’t the only Presidential aspirant in that era who reached for that brass ring, only to miss out and wind up largely forgotten. Today, I want to tell the story of Henry Krajewski.

Krajewski owned a pig farm in Secaucus, New Jersey. At its peak, his farm was home to 4,000 hogs. Krajewski also liked to drink and hang out with friends, so he opened a bar across the street from his farm. He named it “Tammany Hall,” after the New York political machine.

He was evidently something of a renaissance man. Despite dropping out of school after ninth grade, Krajewski claimed to be able to speak and understand six languages and to be able to play seven instruments (piano, accordion, guitar, banjo, organ, drum, and bugle).

In 1949, Krajewski got into politics by running for a town council seat in Secaucus. Rather than running as a Republican or a Democrat, however, he formed his own party. He initially dubbed it the Poor Man’s Party; over the years, he would call it the American Third Party or the Jersey Veteran’s Bonus Party. But it was fundamentally a vessel for Krajewski and his many, many runs for office.

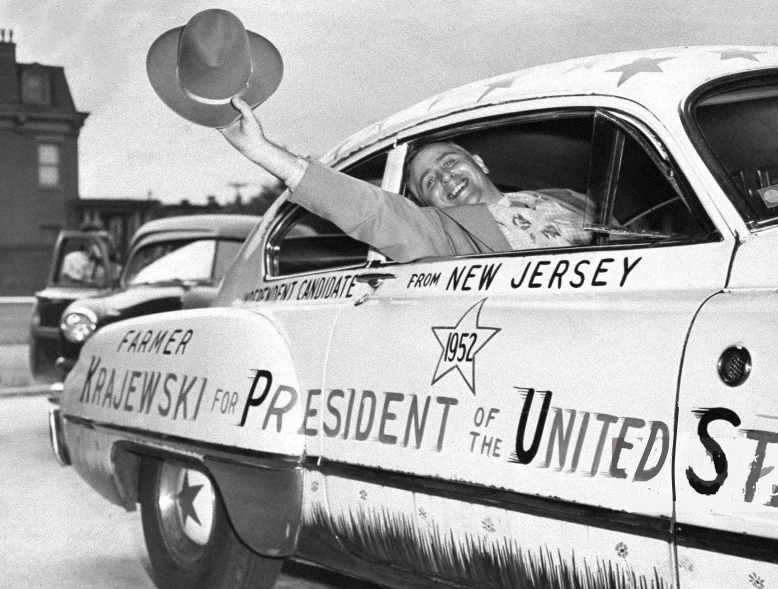

He lost that town council race, along with a race for county freeholder the next year. But in 1952, with his 40th birthday approaching, Krajewski decided to aim higher: he ran for President under his Poor Man’s Party banner.

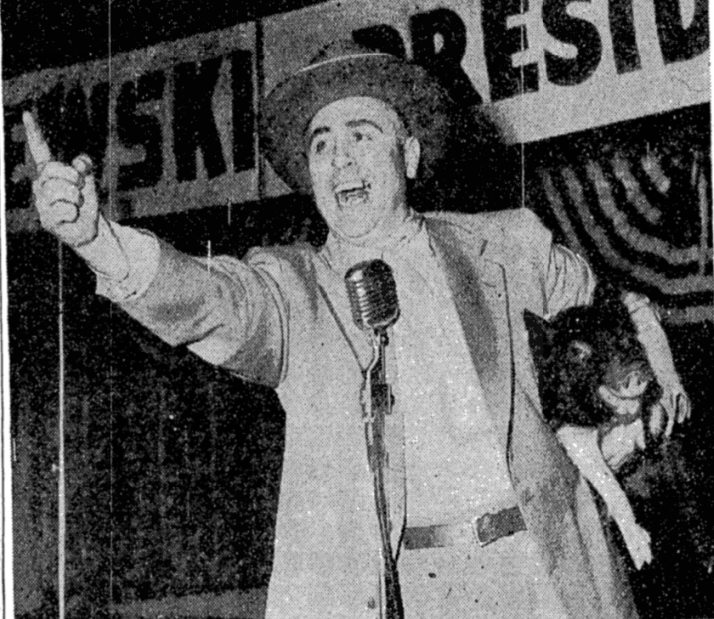

He went to Trenton with his candidacy forms (including 1,136 signatures) in one hand, a black-and-white pig in the other, and a ten-gallon hat on his head. His forms were in order – he’d even chosen a running mate, an ex-coal miner named Frank Jenkins – and he was certified as a candidate.

Like Kefauver, Krajewski was a populist. His platform, which he called the “Square Deal,” was… a bit idiosyncratic.

He favored lowering the age limit to collect Social Security from 65 to 60. He also called for a bonus for all veterans, funded by a national lottery. He proposed that all school-age children be given a free pint of milk every day. He was strongly opposed to both foreign aid and changes to the design of military uniforms (“They change the style of the uniform every time they get too many in the warehouses… It’s a suit-makers’ graft”). He wanted to drastically reduce taxes on liquor and gasoline.

Perhaps his boldest policy initiative was a one-year income tax moratorium for every American with an annual income under $6,000 (roughly equivalent to $71,000 today). “That will give every man a chance to pay up his debts, or to pay off the mortgage on his home,” Krajewski explained.

He also had an out-of-the-box idea to reimagine the office he sought: the “two-President system.” He reasoned, “If you had a Democrat and a Republican in the White House at the same time, they’d be so busy watching each other that there would be no danger of a dictatorship.”

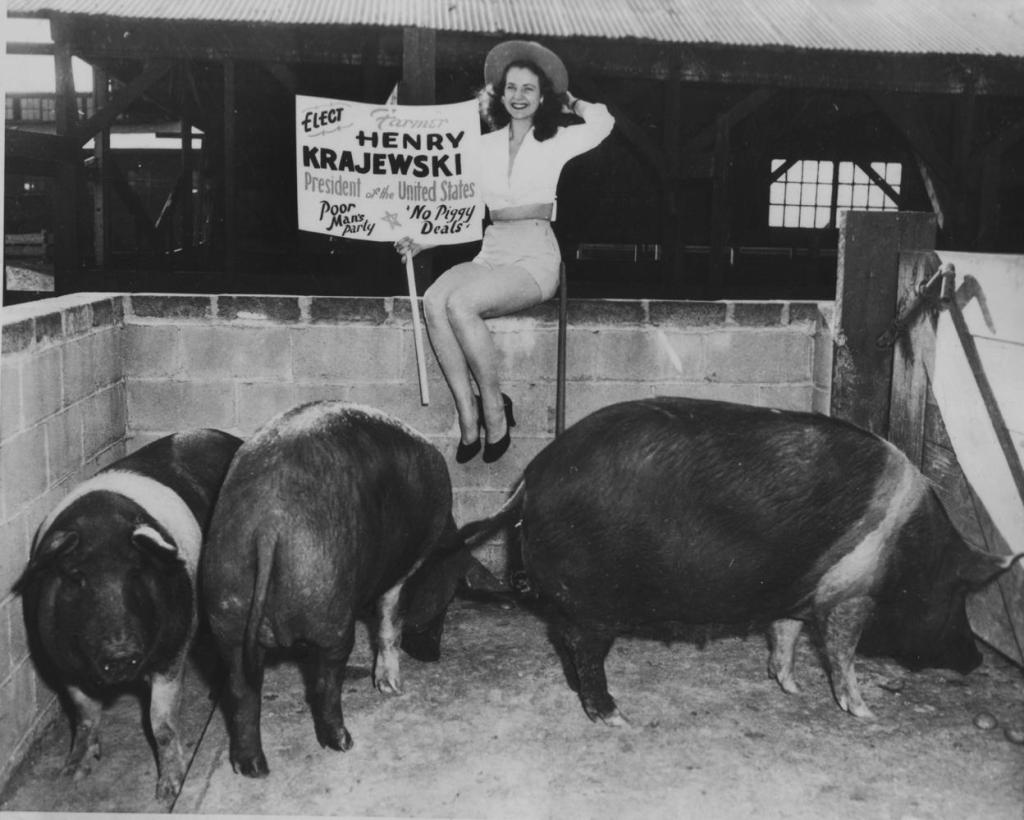

Krajewski wanted an animal mascot for his party, to rival the Democratic donkey and the Republican elephant; he chose the pig. This might seem an obvious choice, given that he was a pig farmer. But he also believed that the pig was a powerful symbol.

A symbol of what, exactly? That depended on when you asked him.

Once, he claimed he’d chosen the pig because “[t]he Democrats have been hogging the Administration at Washington for 20 years, and it’s about time the people began to squeal.” Another time he said, “The pig represents the squeals of the people for a square deal. We’ve had the New Deal and [Harry Truman’s] Fair Deal.”

On yet another occasion, he called the pig “a symbol of peace and prosperity,” pointing out that it was tranquil and that every part of its carcass was usable. “Who wants to eat a donkey or an elephant?” he asked.

Krajewski went hard on the pig theme. He gave speeches while clutching a pig under his arm. And his campaign sported slogans such as “No More Piggy Deals.”

Krajewski launched his campaign with bold aspirations. “He has traveled half the United States buying pigs for his farm,” read one campaign statement, “now he intends traveling the other half stumping for votes.”

This turned out to be a striking exaggeration. Most of Krajewski’s campaign events took place within walking distance of his bar.

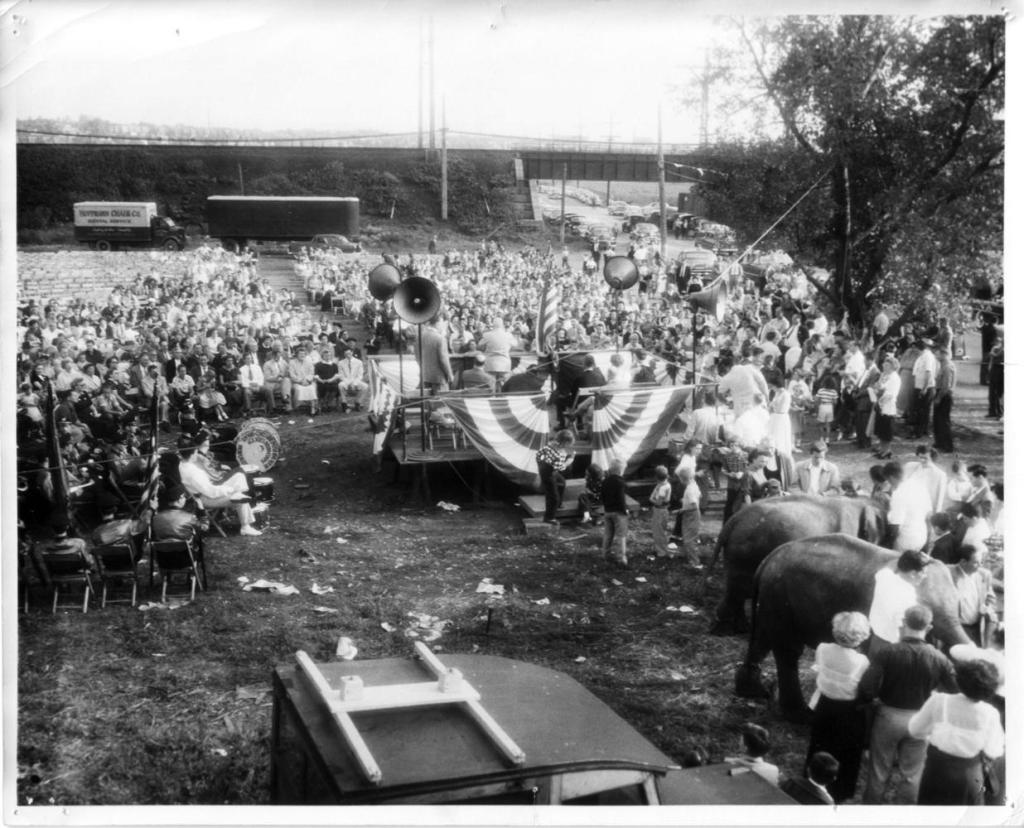

Secaucus town historian Dan McDonough, who attended these rallies with his father, remembered them vividly. “He would have live donkeys, live elephants, and I’m not just talking one elephant, he’d have three, four elephants there,” McDonough said. “The donkeys would be there, the pigs would be there. It was almost like a petting zoo.”

The New York Times reported that at one rally, Krajewski gave away 20,000 ears of corn, 800 gallons of clam chowder, and 30 barrels of birch beer.

Krajewski did occasionally take his campaign across state lines. In May, he took his campaign car to Exeter, New Hampshire. In September, he stood on a beer keg at the corner of Broadway and 69th in New York City, handing out rulers and giving a stump speech attacking “machine politics” (a very Kefauver-esque theme). He reportedly drew a crowd of hundreds, many of them schoolkids who came for the free rulers. Krajweski also donated 20 roast pigs to the kickoff celebration for the Brooklyn Week for the Blind.

Like Kefauver, Krajewski’s dogged efforts could not carry him to the Oval Office. He received a total of 4,203 votes. The candidate elegantly summed up the result by saying, “It wasn’t enough.” (In retrospect, his campaign made a strategic error by failing to get on the ballot in any state other than New Jersey.)

Undaunted, Krajewski was back on the trail the next year, running for Governor of New Jersey. He was briefly embroiled in a campaign scandal, when he claimed a handshake deal with Elmer Wene, who’d lost the Democratic primary. (Wene was a chicken farmer, so perhaps they bonded over agriculture.) Krajewski claimed that he’d agreed to drop out so that Wene could run in his place. This plan was squashed by the Secretary of State, who ruled that Wene couldn’t run since he’d already lost the primary. Krajewski stayed in the race and finished fourth, collecting 12,881 votes.

In 1954, Krajewski was back yet again to run for the U.S. Senate seat being vacated by Robert Hendrickson (he of the juvenile delinquency probe). This time, he added a new plank to his platform: total support for red-baiting Senator Joseph McCarthy. This didn’t mean, however, that Krajewski would stoop to mudslinging himself.

“People admire me because I don’t run a smear campaign,” Krajewski told the Times. “They know I’m for McCarthy because I think he’s a good American.”

He came up short again, but he may have changed the outcome of the election. Krajewski received over 23,000 votes in a race that Republican Clifford Case won by just 3,400 votes over Democrat Charles Howell. Since the majority of Krajewski’s votes came from his home base of Hudson County, a liberal stronghold, some Democrats charged him with costing Howell the seat. (The reality is more complicated. Case was a liberal Republican who staunchly opposed McCarthy, so Krajewski may have received as many votes from pro-McCarthy right-wingers as he did from disaffected Dems.)

Krajewski had his own beef: he charged election fraud. “I am confident that I will get better than 35,000 votes when the final, honest count is made,” he said. He claimed that he’d received calls from voters claiming that “when they tried to vote for me, they found the key of the voting machine over my name would jam.”

(This wound up demonstrating a political truism: if you repeat a lie often enough, people believe it. By 1956, when Krajewski was running for President yet again, several papers incorrectly credited him with the 35,000 votes he claimed to have won in ’54.)

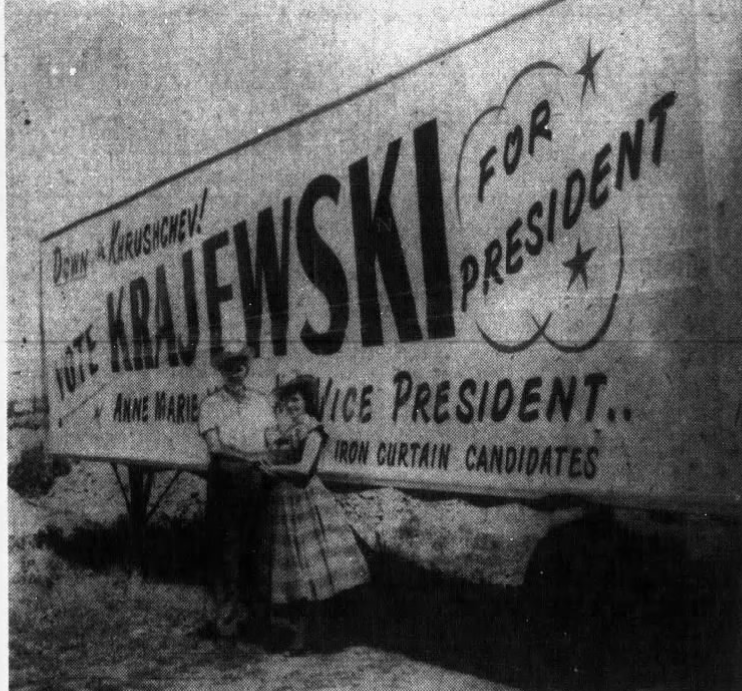

Doubtless noticing the upward trend in his vote totals, Krajewski perhaps felt his time had come in 1956. In a surprisingly progressive move, he selected a female running mate: Anna Marie Yezo, a housewife from North Bergen. At her suggestion, he added a new campaign plank for the ladies: a “compulsory two-month training for girls in outdoor life and helping the farmer’s wife.” He also had a new foreign-policy idea: annexation of Canada “to get back the money we loaned to England.”

In ‘56, Kefauver had to overcome his wife’s opposition to a second Presidential run. Krajewski apparently also faced resistance at home. “She’d be a lot happier about my running for president,” he said of his wife, “if she thought I had a good chance of winning.” (It’s possible Nancy Kefauver felt the same way.)

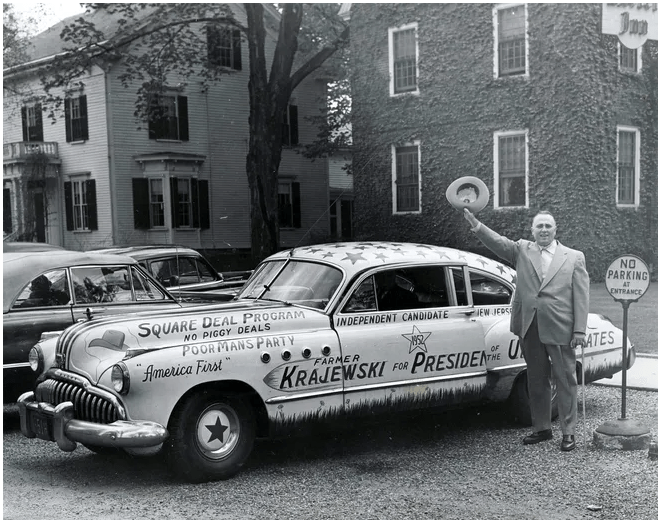

Having learned the limitations of his Secaucus-centric campaign in 1952, Krajewski took his show on the road. In July, the Times reported that he was traveling in his “highly decorated” 1949 Buick to the Democratic and Republican conventions, where he planned “to present his views.” (No such presentation happened, but he claimed to have talked to Native Americans, transportation workers, and farmers in several cities during his trip.)

Also, in 1956 Krajewski figured out how to use his status as a candidate to get stuff. Both Dwight Eisenhower and Adlai Stevenson attended the 1956 World Series between the New York Yankees and the Brooklyn Dodgers, using tickets gifted by the teams. Krajewski wrote to both teams asking that he be extended the same courtesy. “I asked for a bleacher seat,” the man of the people said. “Beggars can’t be choosy.” Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley bit on his pitch and gave him a ticket to the opener.

Not all of his stunts were quite so successful. In July, the Republican held a $100-a-plate “Salute to Eisenhower” luncheon in New York. Krajewski booked the restaurant across the street and hosted a $1.98 pork dinner, putting a sign in the window reading: “Walk Across the Street and Save Yourself $98.02.” Sadly, few took him up on the offer; reported attendance was in the high single digits.

In the fall, the Presidential race was jolted by a pair of international incidents – the Suez crisis and the failed Hungarian revolt. These incidents produced a rally-round-the-flag effect that boosted Eisenhower and essentially closed off any hope of an upset.

Ever the patriot, Krajewski urged his supporters to vote for Eisenhower, calling the President “the only candidate who can give freedom to the countries behind the Iron Curtain, because he has the experience as Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces.” He gamely added that the American people needed to “put the best foot forward and elect a man who is the best in this critical situation.”

He did not, however, withdraw from the race.

Like Kefauver, his second Presidential campaign was less successful than his first; he received only 1,829 votes (all in New Jersey, again the only state where he was on the ballot). It’s hard to say how many votes his noble late endorsement of the incumbent cost him, but it had no discernable effect on the election; Ike won the Garden State by 30 points.

In 1960, Krajewski faced the same dilemma as Kefauver: the Presidential election and the Senate election (Case was seeking a second term) occurred in the same year. Unlike Kefauver, Krajewski passed on the Senate race to take a third try at the Presidency. Sort of.

On July 15, 1959, his 47th birthday, Krajewski announced that he would run for President again. He claimed that his campaign would include a horseback ride to California “to warn the nation of the threat of communism.”

He didn’t do this, although he did drive a campaign-themed tractor-trailer across the country. Alas, the New Jersey Secretary of State rejected his candidacy petition (which Krajewski called “a dirty lousy deal that stinks to high heaven”). The election came and went, and he did not receive any recorded votes.

While his presidential aspirations ended with more of a whimper than a bang, Krajewski wasn’t through with politics. He mounted another bid for Governor in 1961, and for several lower offices as well. In 1964, he offered himself to Lyndon Johnson as a running mate. LBJ never responded.

Perhaps it’s just as well, because Krajewski’s health was failing. In 1965, he lost a leg to diabetes. The following year, he staged a one-man revolt against New Jersey’s new state sales tax, closing his bar for two weeks in July as a “protest demonstration.” (Critics claimed that this was just his usual summer vacation, a charge he denied.)

He geared up for another run against Case for Senate, but had to abandon it due to his health issues. In November of that year – shortly after the elections – he died of a heart attack at age 54.

Obviously, Henry Krajewski’s story is a colorful one, and I enjoyed researching it. But does he have any lessons for us today? I think so.

First, if you’re going to be a fringe candidate, doing so near a major media center is great for publicity. (The New York Times devoted far more column inches to him than to any other minor candidate of the period, because he was right in their backyard and readily available whenever they needed “local color” to fill space.)

Second, Krajewski’s views were far more typical of the average American than many political strategists would imagine. His platform was illogical and didn’t map any more legibly on the left/right divides of the 1950s than it does today. His views on Social Security and free milk for kids would place him on the far left side of the spectrum, while his anti-tax and pro-McCarthy stances would group him with the far right.

Because he didn’t fit in with either side of the aisle, he might today be called a “swing voter” or a “moderate.” But there was nothing moderate about him. Recent political research suggests that a lot of swing voters – especially less politically engaged ones – are more like Krajewski than some mythical Capitol Hill centrist. They tend to have a grab bag for left-wing and right-wing views that might be incoherent, but are sincerely held.

Candidates seeking to appeal to those swing voters might do well to take a page from Krajewski’s book, to the degree that such a book exists.

Third, there’s something great about America that even a humble pig farmer and tavern owner with a grab bag of weird views can run for the highest office in the land. You don’t need a million-dollar super PAC, expensive campaign strategists, or a big-time political apparatus behind you. All you need is the signatures of a couple thousand friends, and a willingness to put your name forward. (And an indifference to landslide defeat. That helps too.)

One more thing: Like many of the great candidates – Kefauver included – Krajewski had a campaign song written in his honor. Bernie Witkowski and his Silver Bell Orchestra wrote the “Hay Krajewski Polka” to celebrate the man. You can hear it here:

Lyrically, it’s not as sophisticated as “Estes Is the Bestes” or “Senator From Tennessee.” But it gets the point across (“Farmer! Senator! Governor! President!”), and it’s quite catchy (if you’re a polka fan, which I am). The animal noises at the end are a nice touch.

Unlike Kefauver’s songs, the “Hay Krajewski Polka” is still played today. As recently as 2014, it was played at a Polish parade in Philadelphia.

As legacies go, it’s not bad. Hay, Krajewski, hay!

Leave a comment