In my piece last week busting myths about the Senate’s juvenile delinquency hearings – and in particular the small portion of those hearings that looked at the comic-book industry – I didn’t have space to include my favorite portion of the hearings. So I’ll include it here instead.

One of the dramatic high points of the hearings was the testimony of William Gaines, publisher of EC Comics. Gaines’ father Max founded EC (which stood for “Educational Comics”) in 1944. Max Gaines primarily published comic books with an educational, Biblical, or gentle humor focus, aimed at young children.

Unfortunately, Max died in a boating accident in 1947, and 25-year-old William took over. He had little interest in the kinds of comic books his father made.

He rebranded EC as “Entertaining Comics” and downplayed his father’s old educational focus in favor of crime, horror, suspense, and science fiction. He published such titles as “Tales From the Crypt,” “The Vault of Horror,” “Crime SuspenStories,” and “Weird Science.”

The new EC Comics were quite popular. However, they also put Gaines and his company squarely in the cross-hairs of the juvenile delinquency subcommittee.

Gaines volunteered to testify before the subcommittee, determined to defend his company’s approach to comic book. By all accounts, he failed. Even the most diehard comic-book fans concede that Gaines’ performance at the hearings was a disaster. It was so bad that in the decades since, a story has sprung up that he was amped up on Dexedrine, which wore off over the course of his testimony. (As far as I can tell, there’s no evidence that this was true.)

At one point, Gaines got into an argument with subcommittee counsel Herbert Beaser about whether there was a limit to what EC would include in a comic book. Beaser asked if the only test for his content was whether it would sell. Gaines countered that he was also limited by “the bounds of good taste.”

This was too much for Kefauver, who then held up a copy of a recent issue of “Crime SuspenStories,” as shown below:

They then engaged in this dialogue:

KEFAUVER: Here is your May 22 issue. This seems to be a man with a bloody axe holding a woman’s head up which has been severed from her body. Do you think that is in good taste?

GAINES: Yes, sir, I do, for the cover of a horror comic. A cover in bad taste, for example, might be defined as holding the head a little higher so that the neck could be seen dripping blood from it, and moving the body over a little further so that the neck of the body could be seen to be bloody.

KEFAUVER: You have blood coming out of her mouth.

GAINES: A little.

KEFAUVER: Here is blood on the ax. I think most adults are shocked by that.

Kefauver then pointed to another EC comic on display. “It seems to be a man with a woman in a boat and he is choking her to death with a crowbar. Is that in good taste?” Incredibly, Gaines replied, “I think it is.”

The publisher was bailed out by another subcommittee member, Senator Thomas Hennings of Missouri, who said, “I don’t think it is really the function of our committee to argue with this gentleman.”

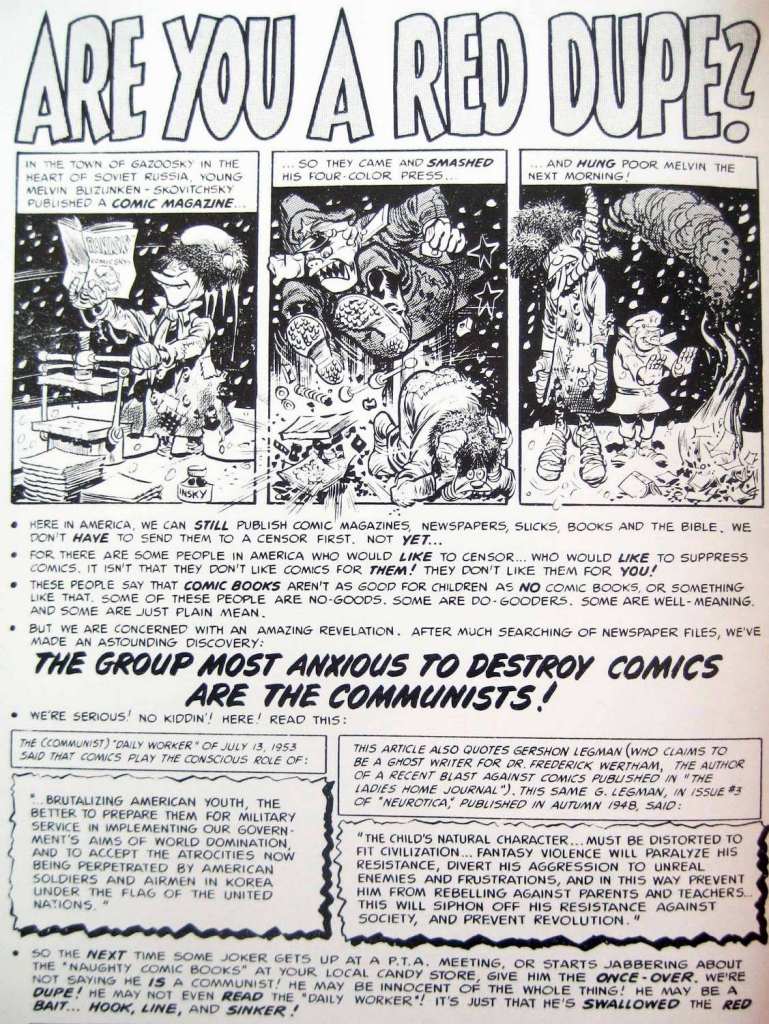

But Gaines was then asked about a circular entitled “Are You a Red Dupe?” He admitted writing it, and said that he planned to run it in his comic books. The circular evoked Red Scare language to push back against criticism of comic books. “There are some people in America who would like to censor… who would like to suppress comics… The group most anxious to destroy comics are the Communists!” the circular read.

Gaines tried to tap-dance a bit by claiming that the circular didn’t technically say that anyone who favored censoring comics was a Communist. But his verbal hair-splitting went over poorly with the subcommittee. By that point, the damage was already done.

In the wake of the hearings, sales of comic books plunged. Gaines urged his fellow publishers to band together and do something to save the industry’s reputation. What they did was to establish the now-infamous Comics Code Authority, which imposed standards on the industry and required publishers to submit comics for approval.

Gaines initially refused to join the CCA. But when retailers refused to sell his comics without the CCA seal, he reluctantly began submitting them for approval. Predictably, this went poorly, and Gaines pulled EC out of the comic-book business entirely by 1956.

He did continue publishing one title, however, one you’ve probably heard of: Mad magazine. Many of his former comic-book editors and artists joined the staff of Mad, which was not subject to the CCA.

In fairness to Gaines, I would point out that his testimony was not a total disaster. In one of his better moments, he pushed back against accusations that his comics were racist. He said that one of his magazines that had been cited for using racial slurs had, in fact, intended to demonstrate the evils of prejudice and mob violence.

“This is one of the most brilliantly written stories that I have ever had the pleasure to publish,” Gaines told the subcommittee. “I was very proud of it, and to find it used in such a nefarious way made me quite angry.”

Later, after the exchange about the bloody axe and the severed head, Kefauver returned to the comic that Gaines had defended as being about the evils of prejudice. “I can’t find any moral of better race relations in it,” he said, “but I think that ought to be filed so we can study it and see and take into consideration what Mr. Gaines has said.”

This line is always omitted from retellings the comic book hearings, because it complicates the story of the hearings as a show trial and Kefauver as a publicity-hungry censor. It demonstrates one thing that was very true of Kefauver: he was always willing to listen, even to people with whom he disagreed.

Leave a comment