Though nobody knew it at the time, 1960 would be Estes Kefauver’s last political campaign. It was also the most challenging campaign of his career.

Sure, he’d been elected to the Senate twice before. But in the eyes of Volunteer State conservatives, he’d just been lucky. In 1948, they said, he’d benefited from a three-way race and a split in the Crump-McKellar machine. In 1954, he’d beat Rep. Pat Sutton, whose terminal case of foot-in-mouth disease (and the rumors of the mob funding his campaign) helped doom his candidacy.

This time around, Kefauver faced a serious and well-respected opponent who focused his campaign on a single issue: segregation. Both within Tennessee and nationally, Kefauver’s race was seen as a litmus test for whether the South was ready to accept advances in civil rights for black Americans. It was also a test of whether Kefauver’s brand of progressive populism was still viable, as FDR’s old New Deal coalition continued to splinter.

Walking Away from A White House Bid

Before all that, however, he had a decision to make: Should he run for the Senate again, or make another try for the Presidency? For the first time since he first joined the Senate, he was up for re-election in a Presidential year.

In theory, it would be possible for Kefauver to run for re-election to the Senate and for the Presidency at the same time. (Lyndon Johnson did exactly that the same year.) But Buford Ellington – no ally of his – was in the governor’s chair, meaning that Kefauver could expect little if any help in either campaign. For another, any liberal statements he made during the Presidential campaign would likely be used against him back home.

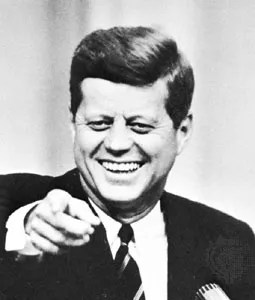

Perhaps this calculation was irrelevant; by most accounts, Kefauver made up his mind quickly after 1956 not to seek the Presidency again. Perhaps, heartbroken by his failures in ’52 and ’56, he concluded that the White House would never be his. Or perhaps he sensed that he was yesterday’s news, and newer candidates were on the horizon. (As early as 1958, John F. Kennedy was outpolling Kefauver in a hypothetical matchup.)

Although Kefauver signaled early that he wouldn’t run for President, his backers seemed reluctant to accept it. It was only after he officially ruled himself out of the primaries that they moved on. In March 1959, he declared that he would not run in New Hampshire, saying, “My only plan in 1960 is to run for re-election to the Senate.” That September, he shot down an effort to place his name on the ballot in Nebraska, telling his supporters: “I appreciate you… thinking of me, but I am not a candidate.”

With the Presidential speculation behind him, Kefauver could focus on his re-election bid, which he formally announced on May 21, 1960. From the beginning, he knew it would be no walk in the park.

Here Comes the Judge

Well before 1960 rolled around, Kefauver was concerned about his popularity in Tennessee. He knew his votes in favor of civil rights had alienated some former supporters. With that in mind, he set to work bolstering his standing. In the fall of 1958, he held “workshops” around the state on local and national issues. He sent out 55,000 Christmas cards in 1959 – 15,000 more than two years earlier. Clearly, Kefauver was gearing up for a serious battle.

Coming into 1960, Kefauver’s most likely opponent was former Governor Frank Clement (the one who called out the National Guard to quell segregationist riots at Clinton High, only to renounce his own decision a couple years later). Clement was ineligible to run for re-election, but he remained widely popular, and he was very ambitious. His organization had backed Ellington for governor, and expected the administration’s support.

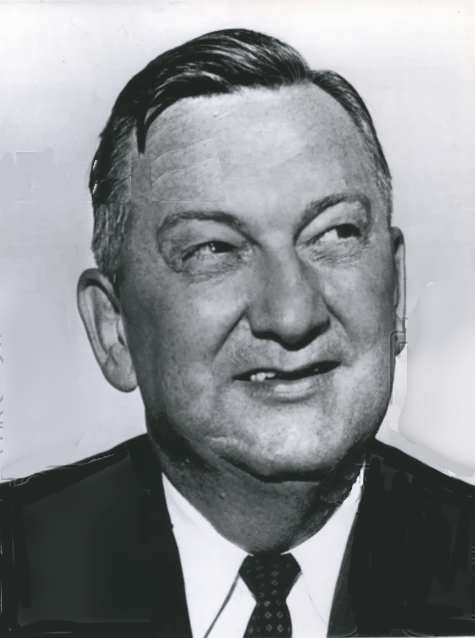

But in early 1960, Clement suddenly decided not to run for Senate after all. Instead, he planned another run for Governor in ’62. That cleared the way for another formidable candidate: Judge Andrew “Tip” Taylor.

Judge Taylor had run for governor in the 1958 primary, narrowly losing to Ellington. His gubernatorial bid had been backed by many prominent state figures, including ex-Governor and Kefauver ally Gordon Browning. He could also expect the same support from the Ellington administration that Clement was counting on.

Judge Taylor wasn’t a lightweight like Pat Sutton. Kefauver had his hands full in this race, and he knew it.

Kefauver vs. the Klan

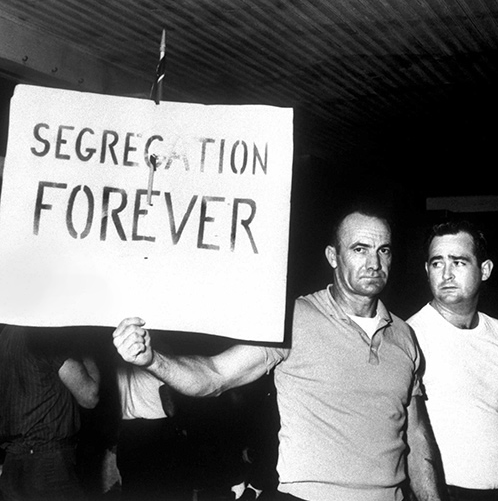

Taylor had not been particularly ideological when he ran for Governor, but he understood that the way to beat Kefauver was to run to his right, especially on civil rights. Kefauver’s votes in favor of the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960, as well as his refusal to sign the pro-segregation Southern Manifesto in 1956, sat poorly with many voters in Tennessee.

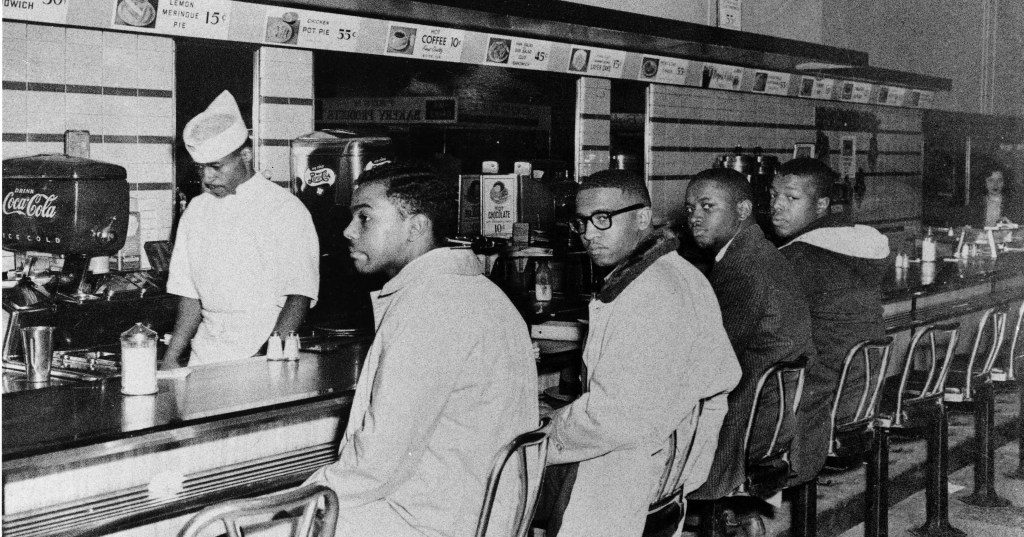

Racial unrest was rising sharply in the South during this time. In addition to the bombing of Clinton High in 1958, there was the 1957 showdown in Little Rock between Governor Orval Faubus and Federal troops sent to help black students enter school. 1960 saw the first wave of sit-ins at segregated lunch counters, spreading from North Carolina across the South.

This terrified many Southern whites, who blamed the Civil Rights Acts and the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education for stirring up trouble where (in their minds) none had existed. Against this background of fear and anger, multiple candidates embraced openly segregationist campaigns, including in Tennessee’s neighbor, Arkansas.

Faubus – who had been relatively moderate on racial issues before shifting to a hard segregationist stance during his term – cruised to re-election in 1958 and was named one of America’s ten most admired men in a Gallup poll. Also in ’58, Dale Alford ran and won a last-minute write-in campaign against U.S. Rep. Brooks Hays, who represented Little Rock, solely on opposition to school integration.

Given all that, Taylor saw embracing segregation as his path to victory. And embrace it he did, with little subtlety. He avoided interacting with black people on the campaign trail to the point of ridiculousness. At one event, Taylor was shaking hands with workers coming out of a factory in Memphis; every time a black worker walked by, Taylor turned away.

Time magazine wrote, “As Tip Taylor campaigned through the flatlands and the Smokies he thumped Estes Kefauver for virtually every integrationist crime except the Emancipation Proclamation.”

Taylor proclaimed that he “would have definitely joined” the Southern Senators who filibustered the Civil Rights Act of 1960. He went on to claim, “This so-called civil rights bill… will allow Federal referees or Federal agents to come into Tennessee and tell us who can and who cannot vote. They would simply take over our election machinery and deny to Tennessee the right of holding its own elections which is granted by the Constitution.”

Taylor argued that Kefauver was a traitor to the South and his home state. “Every state is entitled to two Senators,” Taylor thundered. “New York has two Senators to represent the people there, and I am tired of us supplying them with an extra Senator. He votes just like Hubert Humphrey.”

In response to these attacks, Kefauver stood by his record and appealed to the better angels of the voters’ nature. To critics of the 1960 Act, he said, “I thought it was a fair and just bill, and I could not clear it with my conscience to vote against the right to vote. I don’t know how we can hold our heads up in the world if we deprive people of this right.”

To whites terrified of civil rights protests, Kefauver pointed out that denying blacks the vote shut them out of the system, making other forms of protest more appealing. “If we want to have more responsibility on the part of Negro citizens and others,” he said, “with that responsibility should come the right to vote.”

At times, Kefauver went farther, directly challenging the conscience of the voters. “I voted for the civil rights bill this year… because I felt it was right,” he said, “and I think you feel it was right too. If there is anyone here who doesn’t feel every qualified citizen should have the right to vote, let him hold up his hand.” Inevitably, no one raised a hand.

Taylor dismissed Kefauver’s appeals to conscience, claiming that the incumbent’s civil rights votes were just an attempt to curry favor for his national campaigns. “[W]hen your ambition causes you to turn your back on your own people, as it has my opponent,” Taylor said, “then it is time for a change.” As a Senator, Taylor vowed, “[y]ou will never find me playing post office with a bunch of Northern liberals.”

In response, Kefauver pointed out that he needed the support of Senators in all regions on issues like the TVA. He also asked what, exactly, was wrong with being nationally popular. “How does it disqualify you to be a senator because someone thought you were qualified to be a candidate for President?” Kefauver wondered.

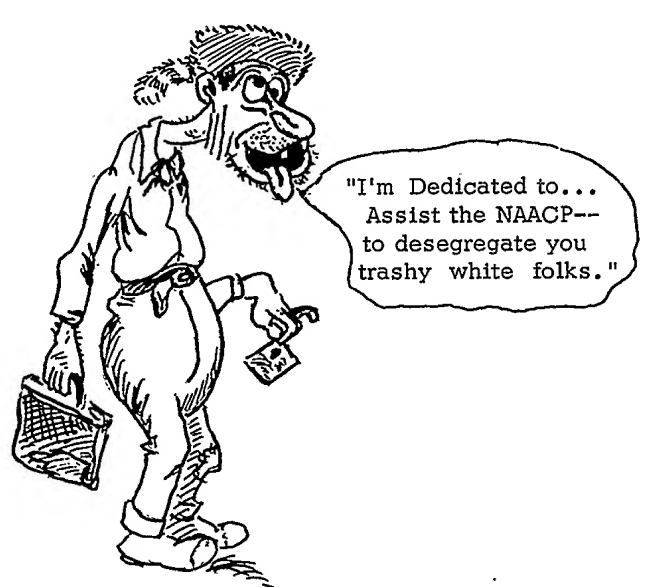

As ugly as Taylor’s rhetoric could get, it was nothing compared to that of his supporters. Taylor was endorsed by the Ku Klux Klan and White Citizen’s Council throughout the South. Those supporters spread wild rumors, claiming the Kefauver campaign was a plot against America by Yankees, Jews, Communists, and blacks.

Tennesseans were bombarded with mailings from anonymous groups containing appalling statements and accusations. One was a “Dear Comrade” letter endorsing Kefauver from a fictional group called “The International Committee of Human Brotherhood,” which stated that one of its goals was “to take control from the whites.” Another was captioned “ESTES IS THE BESTEST LIBERAL-SOCIALIST IN THE LAND.” Numerous circulars raised the specter of interracial marriage (including a poem which termed it “racial suicide”). Another warned of “hell-inspired Jews” seeking “to destroy the white race.”

Kefauver was able to laugh off some of these attacks. In response to a circular showing him shaking hands with a black man in California, Kefauver replied, “I plead guilty to shaking hands with Negroes.” But as the ugly smears and anonymous mailings piled up, he grew frustrated.

The Kefauver campaign filed numerous election-law complaints, which led (after much prodding by the Civil Rights Division of the Justice Department) to an FBI investigation. Kefauver also condemned Taylor for refusing to disavow these attacks.

“There have been misrepresentations, lies, innuendoes, [and] smears,” Kefauver complained. “Judge Taylor has said that he knows of it, but he has not lifted a finger to stop it. It looks to me like a planned part of the campaign.”

Kefauver’s battle against the racists and segregationists was challenge enough, but he also had to deal with another hostile constituency: angry pharmacists.

Kefauver’s War on Drugs

In 1958, Kefauver’s Senate Subcommittee on Antitrust and Monopoly began its investigation into prescription drug safety and pricing (which would lead the Kefauver-Harris Drug Act).

He knew that this would lead to controversy, and he agonized with the subcommittee’s lead staffer, Paul Rand Dixon, over whether to launch the probe. In the end, believing the hearings to be vital to the public interest, Kefauver went ahead with them.

As the election drew closer, though, Kefauver had second thoughts. “I never should have gotten mixed up in this drug thing,” he lamented to adviser John Blair. “Now I’ve got the drug people, the pharmacists and the doctors all stirred up. They’re going to throw the book at me down there.”

One pharmaceutical company sent a representative to Tennessee to explore ways for the drug companies to quietly back Taylor. Once this visit became news, Kefauver had an issue for his populist crusade.

He charged that “a big slush fund [was] being raised by the big pharmaceutical manufacturers and by some druggists who have been taken in by the manufacturers in an effort to defeat me. The reason is they don’t want the price of drugs to come down.”

Ironically, Taylor received virtually no help from the drug companies – or the steel companies, automakers, or other corporations with axes to grind over Kefauver’s anti-monopoly work. He did, however, gain the backing of “Druggists for Tip Taylor,” a coalition of Tennessee pharmacists annoyed by Kefauver’s accusations of profit-grabbing.

Throughout the campaign, Kefauver was careful to aim his attacks the pharmaceutical companies, not the pharmacists themselves. Later on, however, he started going after the druggists too. “Whenever you see a drugstore that is supporting my opponent,” he told his supporters, “you know he wants to keep prices high. You just go to another drugstore.”

Kefauver Gets a Little Help From His Friends

As the race moved into July, it became evident that Kefauver might actually be in trouble. The New York Times described Kefauver as “waging a desperate fight to retain his Senate seat,” adding that even his supporters rated his odds of survival at close to 50-50.

“As he roamed the towns and villages of Tennessee last week,” reported Time, “Senator Estes Kefauver seemed his old-shoe self. But at close handshake, there was a big difference: campaigning for a third Senate term, the Keef was running scared.”

He ran himself ragged, even beyond his usual pace. He traveled an estimated 26,000 miles during the primary, making six to eight speeches a day. An adviser who encountered Kefauver late in the campaign worried for his health, saying he “looked like death itself.”

Fortunately, Kefauver didn’t have to rely solely on his willingness to campaign himself to death and the ragtag staff that the New York Times referred to as “a corps of volunteer housewives and college youths.” He had friends in his corner.

One of Kefauver’s strongest allies was organized labor. The AFL-CIO made Kefauver their most-supported Senator in the 1960 political cycle. In addition to $40,000 in contributions, they provided extensive grass-roots support, making calls and passing out literature on his behalf.

Kefauver also received support from around the nation. His former running mate, Adlai Stevenson, provided a typically eloquent endorsement. “[N]o member of the Senate has served the people – and I mean all the people – more faithfully,” wrote Stevenson, who added, “I view your re-election as absolutely imperative both from the standpoint of the country and of the Democratic Party.”

John F. Kennedy also sent Kefauver a supportive telegram, stating that he was “counting strongly on your support and friendship during the coming campaign and during the years of our administration.”

Kefauver received help from more unexpected quarters as well. His would-be rival Frank Clement, afraid that a narrow loss would establish Taylor as a leading gubernatorial candidate in ’62, signaled his support for the incumbent. Clement’s father even showed up at a Kefauver rally.

In addition, Kefauver received telegrams from several of his fellow Southern Senators, endorsing his re-election. Those telegrams come not only from fellow liberals like Ralph Yarborough of Texas or allies from the TVA fights like Alabama’s Lister Hill and John Sparkman, but even from segregationists like Georgia’s Herman Talmadge, South Carolina’s Olin Johnston, and Mississippi’s John Stennis. The Kefauver campaign reprinted those telegrams in newspaper ads, shoring up the incumbent’s Southern bona fides.

But the coup de grace came the Saturday before the primary. The Young Democrats held a rally in Nashville, with Lyndon Johnson as the guest of honor. Johnson’s speech verged on an open endorsement of Kefauver, whom he called “my beloved colleague.” He also implicitly rejected Taylor’s charge about the importance of having a “real Southerner” in the Senate.

“Wherever I may go,” Johnson told the audience, “I will never speak as a Southerner to Southerners or as a Protestant to Protestants or as a whites to whites. I will only speak as an American to Americans – whatever their region, religion, or race.”

As Johnson departed the rally, he greeted Kefauver with a warm embrace.

Meanwhile, Taylor was not receiving the help he’d been promised from the Ellington administration. Perhaps Kefauver might be able to pull this one out after all.

A Surprise Landslide

Kefauver would indeed pull it out. And it wasn’t just a squeaker, either: Kefauver rolled up 64.5% of the primary vote, crushing Taylor by almost 115,000 votes.

He won in all but 16 of Tennessee’s 95 counties. The incumbent routed Taylor in Middle Tennessee, as expected. But the Taylor campaign had hoped for a narrow win in East Tennessee; in fact, Kefauver’s margin there was nearly as high as it was in the central part of the state.

West Tennessee was the most pro-segregation area, and Taylor did win there as expected. However, rather than the big margin he counted on, Taylor won the region by just 12,000 votes out of 236,000 cast. His big margins in segregationist counties were countered by Kefauver’s big win in Memphis and his overwhelming margin with black voters, who turned out in record numbers.

Kefauver called his win a victory for Southern progressivism. “The detractors of the South, who tried to say we are a backward people,” he told local reporters, “have been proven wrong.” He hoped his victory would “give great encouragement” to other Southern politicians “who have been wanting to get away from this blind opposition on civil rights, but who have been intimidated by some of the faces around them.”

He also claimed that his big win forecasted success for the Kennedy-Johnson ticket in the fall, calling it “an indication that the South wants to go ahead with the New Frontiers advocated by our Democratic candidate.” That prediction turned out to be mistaken, as Richard Nixon won Tennessee by a 7% margin in 1960, even as Kefauver cruised to re-election.

Taylor supporters, meanwhile, were shocked at the outcome. One of his campaign managers, reacting with the same graceless racism that marked Taylor’s campaign, had this to say: “It’s all right with me. I don’t care. If they want to give the state and the schools and everything else over to the n—–s, I don’t care. No sir.”

Postscript: The Hidden Hand of LBJ?

Looking back, one might wonder how Kefauver went from fighting for his political life to posting a massive victory. And one might notice that he got some lucky breaks along the way: first when Clement decided not to run, then when Ellington backed away from his promise to help Taylor, and then with those last-minute telegrams of support from his Southern colleagues, including several more inclined toward Taylor’s views on segregation.

According to Kefauver biographer Charles Fontenay, those weren’t just lucky breaks. They were engineered by none other than Lyndon Johnson.

After snubbing Kefauver’s committee requests for years, LBJ suddenly found a spot for him on the powerful Appropriations Committee ahead of the 1960 election. Fontenay spoke to a source in the upper echelons of Tennessee politics, who said that it was Johnson who got Clement not to run for Senate, and it was Johnson who convinced Ellington not to assist Taylor. He was also behind the flood of pro-Kefauver telegrams from the Southern Senators.

Now, if you read my article about LBJ’s relationship with Kefauver, you probably have some questions. By most accounts, Johnson never liked Kefauver, distrusted his liberalism and his independent streak, and went out of his way to thwart Kefauver’s hopes of advancement, both within the Senate and in his Presidential dreams. So why would Johnson help him now?

As usual with Johnson, he primarily sought to help himself. Johnson wanted desperately to be President, but he was still viewed as a sectional Southern candidate. To win nationwide, he’d need support in the North and West… from the same voters who loved Kefauver. By ensuring that Kefauver had an easier time getting re-elected to the Senate, LBJ also ensured one less top-tier contender for the Presidency.

Kefauver did send his wife and some key staffers to the Democratic convention in support of Johnson’s Presidential bid. (He himself did not attend, being bound to the campaign trail at home.) And although Johnson didn’t win, he did come away with the VP slot. His gratitude for Kefauver’s support was clear.

For one shining moment, Kefauver got to experience what it was like to be on LBJ’s good side. And thanks to his landslide win, he solidified his reputation for being electorally bulletproof in Tennessee. Sadly, he would never stand before the voters again.

Leave a reply to Better Living Through Chemistry: Kefauver and the Department of Science – Estes Kefauver for President Cancel reply