A couple weeks ago, I saw a comment on my article about Kefauver’s civil rights record from a man named Fred Strong. He said that I’d neglected to mention the bill Kefauver filed on school desegregation – and added that he knew this bill well, because he had written it!

Naturally, this piqued my interest. When I started this project, I figured it was unlikely I’d ever be able to speak to someone who’d worked with Senator Kefauver, since most of those people are no longer with us. The fact that one such person had found me – and commented on my post! – was an incredible stroke of good fortune.

I reached out to thank him for the comment, and he graciously agreed to an interview. I’m glad he did, because his story is fascinating! I’m thrilled to share it with you.

From the Farm to Politics

Fred (everyone calls him “Fred”) grew up in Greendale, Wisconsin, one of the “greenbelt towns” created by the WPA during the Great Depression. Fred’s mother was the assistant administrator of Greendale, which meant that he was immersed in the world of politics from a young age.

Later, his family moved to a farm outside of town; since his parents both worked, Fred was primarily responsible for the farm. He grew alfalfa, cherries, and apples, and raised over 2,000 rabbits. He sold one of his prize rabbits for $5,000, which he used to pay for college.

Fred was a staunch Democrat, having grown up during the presidencies of FDR and Harry Truman. When Dwight Eisenhower won the Presidency in 1952, Fred said, “that was the ultimate political tragedy of my life!” Though just 15 at the time, he felt the need to take action.

He called the Wisconsin Democratic Party headquarters and proclaimed, “I want to join the party!” This was met with shocked silence. They’d already had 200 resignations that day – he really wanted to join them right after a crushing loss?

They were even more dumbfounded when he said he was still in high school: “We don’t have any place for a high schooler!” they told him. Fortunately, Fred attended Marquette University High School, and the university had a Democratic club, so they sent him over there.

At the Marquette Democratic Club, he got to know the state Democratic chairman and the Democratic national committeeman. They quickly realized the value of having high schoolers on board –a source of hard-working free labor – and tasked Fred with creating Young Democrats chapters around the state. He helped established six chapters in his first year.

Writing Bills for Kefauver – While Still in High School!

Fred’s introduction to Kefauver came when the Senator was drafting the agriculture bill in 1954. Having no knowledge of agriculture, Kefauver turned to an old Wisconsin friend, Esther Lipsen, who had managed his campaign office at the 1952 Chicago convention and then moved to Washington at his invitation. (She later married and became Esther Coopersmith, the legendary DC hostess, diplomat, and fundraiser who passed away in March at age 94.)

Kefauver asked Lipsen if she knew someone with farm experience who could write the bill. She turned to her father, a prominent farmer, but he was too busy to help. She then turned to Don Worley, the national committeeman, who told her, “Sure, I’ve got a farmer who can write an agriculture bill!”

He meant Fred. He didn’t tell Lipsen – or Kefauver – that Fred was still in high school. They assumed he was a graduate student at Marquette University. (His voice had already dropped and, as a high-school debate champion, he had a sophisticated vocabulary that made him sound like an adult.) Fred happily accepted the assignment. His first task: learn how to write a Congressional bill.

Fred spent 9 months researching the topic. He learned that the language in the existing bill to reimburse farmers in the event of disaster dated back to before World War II, and it had two major problems. First, the reimbursement amounts were too low, since they had not been increased for inflation. Second, the amounts were the same for everyone regardless of what crops they grew or what animals they raised.

Fred devised a formula to adjust the reimbursement amounts for each farm based on the crops and/or animals that the farm raised. Communicating with Kefauver’s staff solely over telephone and mail, he developed his draft bill and sent it off to Washington. Kefauver reviewed Fred’s draft, liked it, and submitted it for consideration by the Senate. Ninety days later, with only one amendment (to add an appeals committee), the bill became law.

Kefauver called Fred to thank him personally, and ask if there was anything he could do for him. Fred quickly replied, “Yes, Senator. I think it’s time to do something about civil rights and school integration.” After a pause, Kefauver told him, “All right. Write something up and send it to me, and I’ll give it a look.”

Fred proceeded to write a bill that would integrate the schools over a period of years, beginning with the Kindergarten class of 1954 and moving up a grade each year until K-12 schools were fully integrated. He felt this approach would “put kids together before they have prejudice, and let them see each other as people.” He sent the bill to Kefauver, who proceeded to introduce it on the Senate floor. (Fred’s bill was a good fit with the Senator’s gradualist approach to integration, which surely helped.)

Unlike Fred’s farm bill, the school integration bill failed to pass. It took fire from both sides, but to Fred’s surprise, it was civil-rights activists such as Martin Luther King and James Farmer who most strongly opposed the bill, as they favored immediate integration.

Dr. King even spoke to Fred directly to voice his objections to the bill. “If it’s right in 12 years, it’s right today,” King said of school integration. Fred replied that while he agreed philosophically, he believed that integrating immediately would cause a violent backlash. “What’s right is right,” King replied, and he remained firm in his opposition.

Joining the Campaign Trail

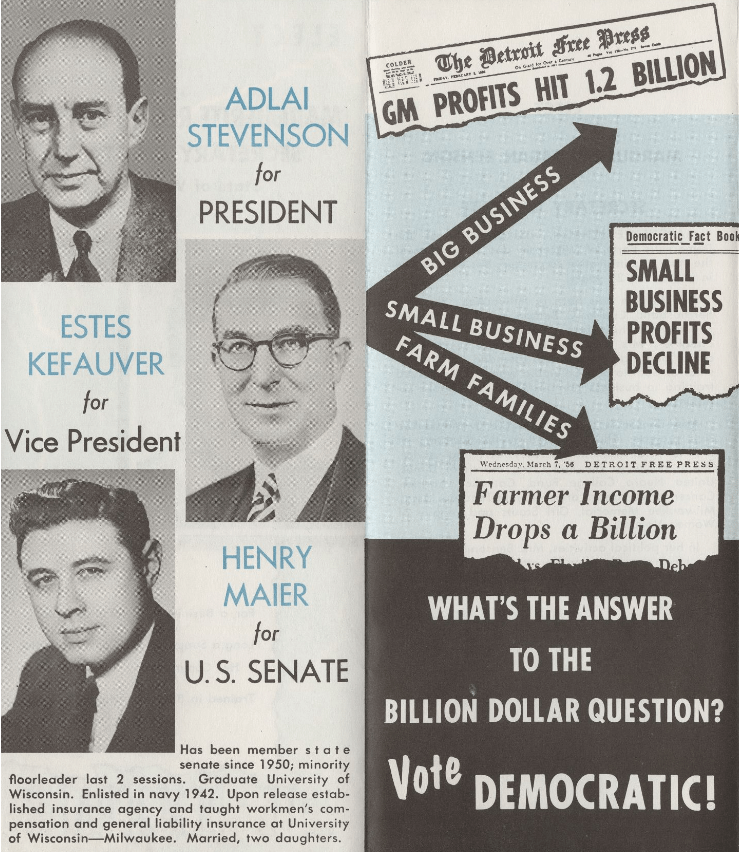

In spite of the failure of the school integration bill, Kefauver remained highly pleased with Fred’s work. So when the Senator ran for the Presidency again in 1956, Fred was one of the eight people he chose to run his primary campaign in Wisconsin. During the campaign, he finally got to meet Kefauver in person.

One of Fred’s key campaign functions was to stand next to Kefauver at events and let him know who he was meeting, so that the Senator could greet them by name. One problem: Fred himself wasn’t good with names.

“They gave me a list of the people who were there,” said Fred, “but sometimes a man would come up, and a woman’s name was next on the list, and then I was in trouble.”

Fortunately, he quickly learned a strategy: He’d approach and say, “Pardon me, what’s your name again?” If the person seemed offended and said, “I’m Councilman Jones, of course,” Fred would say, “Of course I knew that, Councilman. I just couldn’t recall your first name.” Crisis averted!

The primaries introduced Fred to the rhythms of campaign life. Every morning, Kefauver would have coffee with local leaders; at noon, a luncheon with the ladies’ groups; at night, a formal dinner with the community power brokers; and after dinner, the candidate and staff would return to the hotel or campaign HQ to strategize for the next day.

Working by Kefauver’s side, Fred got to see him up close and personal. On one occasion in Milwaukee, the staff assembled at Kefauver’s suite at the Pfister Hotel after a long day on the trail to plan the next day’s schedule. Just one problem: the candidate didn’t come out of his room to join them. The staff waited while five minutes late became ten minutes, then fifteen.

A staffer knocked on Kefauver’s door, and the Senator said, “I’ll be out in a minute!” More minutes passed, and he still didn’t appear. The staffer knocked again, with the same result. Finally, the third time that the staffer knocked – 45 minutes after the meeting was supposed to start – Kefauver finally emerged, clad in his boxer shorts with a bottle of liquor in each hand, and declared: “Hell, let’s drink!” (Fred, who has never been much of a drinker, acknowledged that he had “a beer, or maybe two” that night.)

Although Kefauver’s Presidential campaign came up short, Fred still played a role at the convention that year. When Adlai Stevenson left it up to the convention to choose his running mate, Fred worked hard to secure the nod for Kefauver, recruiting supporters in the Carolinas and Texas.

Ultimately, Fred recalls, the campaign made a deal with New York’s Tammany Hall – despite their coziness with the same underworld figures Kefauver had grilled during the organized crime hearings – to secure Kefauver the VP nod over John F. Kennedy.

“You can run the cleanest campaign in the world,” Fred said, “but there’s always some bad actors out there. If you want to win, you have to make deals with them.” (Kefauver had learned this lesson the hard way back in 1952, when his refusal to make deals against his principles helped cost him the nomination.)

Fred’s working relationship with Kefauver largely ended after 1956, but he remained active in national politics. The Democrats sent him to their national political school in Chicago, an experience which Fred was “almost ashamed of, because of how many dirty tricks they teach you!” (For example, they taught future leaders how to act drunk without actually getting drunk, in order to entice their drinking buddies to spill their secrets.)

How Fred Went from HHH to JFK – and How JFK Adopted the Peace Corps

By 1960 – now in college – Fred had become a ward chairman in Wisconsin, working directly with senior party leaders. He worked as the chairman of the youth committee for Hubert Humphrey’s Presidential primary campaign in the Badger State.

One day, he was stopped on the street in Milwaukee by Marge Benson, a big-time political worker in the state, who insisted that Fred come with her to meet someone. She took him to a local TV station, where he met the candidate that Benson supported: John F. Kennedy himself.

Kennedy greeted Fred by name and said, “I want you with me!” (He later learned that the Senator was so interested because Fred was the one member of Kefauver’s Wisconsin campaign who wasn’t already in Kennedy’s camp.)

Fred demurred, saying that he wouldn’t switch horses in midstream. Kennedy persisted, asking what it would take to get him on board. Finally, Fred laid out his conditions: if Kennedy won Wisconsin and asked Humphrey’s permission, Fred would switch.

JFK did win the Badger State and, good to his word, asked Humphrey if he could bring Fred on. Humphrey agreed, with a condition: in exchange, he wanted Kennedy to pick up a proposal he had been developing with Fred’s help: the Peace Corps.

Kennedy took the deal, and Fred worked with Bobby Kennedy to draft the legislation that made the Peace Corps a reality. On the campaign, Fred was able to observe the dynamic between the Kennedy brothers. “Jack was the face,” Fred told me. “He was the guy people swooned over… Bobby was the brains. And Jack knew it! That’s why JFK put him in the Cabinet, to keep him close.”

A Remarkable – and Still Active – Life

Fred went on to enjoy a lengthy and varied career as a newspaper reporter and editor, lobbyist, and political advisor. He has written legislation for 20 different states, and has served as an advisor to three US Presidents.

Today, at age 86, Fred remains as active as ever. He is a City Councilman in his adopted hometown of Paso Robles, California. He also serves on the Board of Directors for the National Association of Regional Councils, an advocacy and authority for regional planning organizations across the US. He reads over 1,000 pages of legislation a week. And he has no intention of slowing down: “First you vegetate, then you disintegrate,” he says.

Even though he worked directly with Kefauver, he told me that he’s learned some things about the Senator from this site, such as the fact that Kefauver’s office sent out thousands of Christmas cards every year. “I was shocked to learn how many Christmas cards he sent out,” Fred said, “because I always treasured mine.”

I asked whether he thought Kefauver would have been a good President. Fred thinks he would have. “I used to call him a Cadillac engine in a Model T body,” Fred quipped. He said that Kefauver “had a brilliant mind. He could identify a good idea and vocalize it.”

It comes as no surprise Fred has been told many times that he should write a memoir of his experiences. But he’s clearly too busy still living his life – “staying active and vital,” as he put it – to spend a lot of time looking back.

But I’m grateful that he took the time to share a piece of his story with me – and I’m delighted to be able to share it with you.

Leave a comment