Today’s political culture is so partisan that it seems like Americans can’t agree on anything. We’re so bitterly divided that even war, which often unifies countries against an external enemy, can’t bring us together. Whether it’s the question of providing aid to Ukraine to resist Russian invasion, or arguing whether Israel’s invasion of Gaza is justified or genocide, the “rally ‘round the flag” effect seems to be gone.

Wouldn’t it be great if we could revive the spirit of national unity we had in World War II? We had no trouble identifying the good guys and the bad guys in that conflict, and we came together to defeat the forces of evil both in Europe and Asia. What happened to those days?

Yeah, about that. Although our popular narrative of that era depicts an America unified against the forces of the Axis, that wasn’t entirely true. Even once the war was over and the Allies had won, there were still debates over whether America was truly a force for good. There were competing narratives even over the war we’d just fought and won. And there were media-hungry demagogues just as ruthless and nasty as any you’ll find today.

Don’t believe me? Let me take you back to 1949, and the Senate investigation into the Malmedy massacre.

In December 1944, the Axis powers launched the Battle of the Bulge, what would be their last major offensive on the western front. On December 17, near the Belgian town of Malmedy, German SS troops tok a convoy of about 120 American soldiers by surprise. Lacking the numbers or the arms to fight back, the Americans quickly surrendered.

The Nazis had the surrendered Americans stand in a field, and promptly began mowing them down with machine-gun fire. Some of the POWs fled and hid in a nearby café; the SS troops burned the café down and shot those who tried to escape. In all, 84 Americans were killed, left for dead in the snow-covered fields.

However, about 50 Americans survived, either by playing dead or recovering from their wounds. They proceeded to tell the tale of the brutality they had witnessed. Once the Allies were able to regain control of the field where the massacre occurred, they discovered that many of the corpses had either been shot in the head or had their skulls crushed by rifle butts.

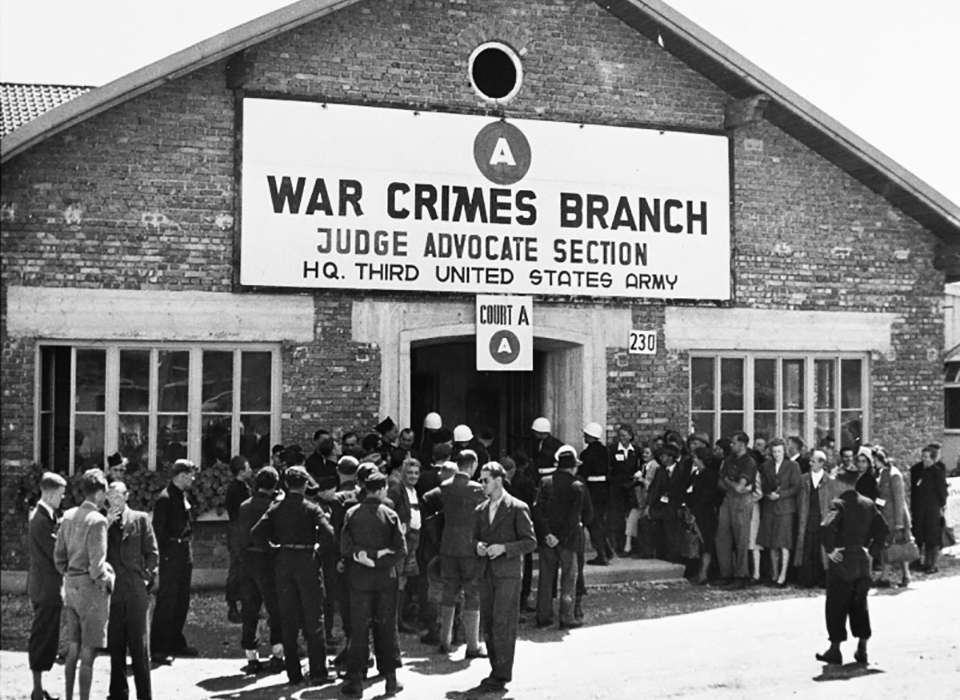

Once the war was over, the Allies rounded up about 75 SS soldiers who were accused of participating in the Malmedy massacre and other war crimes during the Battle of the Bulge. The soldiers were tried in 1946 at the former concentration-camp site in Dachau.

Joachim Pieper, commander of the SS unit responsible for the Malmedy, said he was acting on orders from Hitler to take no prisoners and spare no civilian. Nonetheless, all but one of the defendants were found guilty; 46 were sentenced to death, and 22 others to imprisonment for life.

However, about a year and a half later, the German soldiers recanted their confessions and claimed that their statements had been coerced by torture, starvation, and isolation. They claimed that some of the investigators, who were Jewish, were motivated by revenge rather than justice.

Colonel Willis Everett, who had been the chief defense counsel during the war crimes tribunal, publicly advocated for the defendants. But so did other ex-Nazi soldiers, some German-Americans, and anti-war activists. And at the head of the parade was none other than… Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy!

Let’s pause for a moment. Why would McCarthy, a proud WWII veteran who frequently bragged about his service and combat heroism on the campaign trail, lead a crusade against the US Army on behalf of actual Nazis? Even from him, this seems hard to believe.

Historians suspect that McCarthy may have been driven by multiple motivations. Wisconsin had (and still has) a large German-American population, and he may have made a calculation that this would help him politically with the more, let’s say, unreconstructed members of that group. Others posit that he was motivated by anti-Semitism (a charge reinforced by the unsuccessful smear campaign he mounted the next year against Anna Rosenberg when she was nominated for assistant Secretary of Defense).

Still others believe that his primary motive was attracting attention. As McCarthy would demonstrate with his Red Scare campaign a couple years later – and during the hearings on the Malmedy massacre, as we’ll see shortly – he would go to any lengths necessary to get his name in the papers.

The SS soldiers and their sympathizers raised enough of a ruckus that the Army felt compelled to investigate. They created a commission of judges to investigate the allegations. The commission concluded that some of the pre-trial investigations had been improper, and recommended that some of the sentences be reduced. As a result, thirteen of the prisoners were freed, and 31 of those who had been given death sentences received life imprisonment instead.

That might have put an end to the matter, but one member of the commission – Edward Van Roden – made public statements indicating that he believed at least some of the abuse allegations. (The commission made no formal finding on whether the defendants had been tortured.) In February 1949, The Progressive magazine ran an article under Van Roden’s byline, based on a Rotary Club speech he gave about the commission. Notably, the article quoted Van Roden as saying that “all but two of the Germans in the 139 cases we investigated had been kicked in the testicles beyond repair. This was standard operating procedure with our American investigators.”

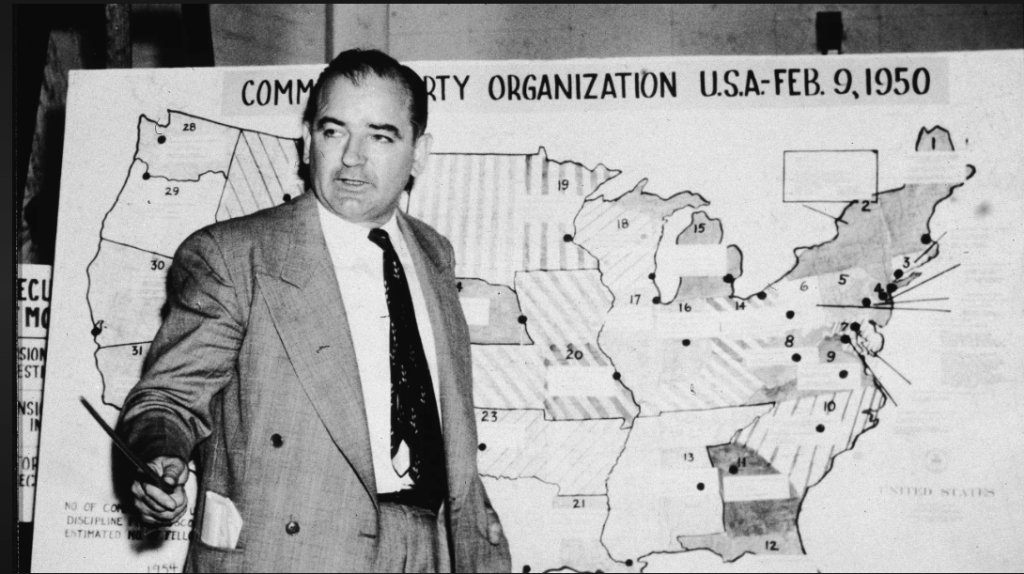

Naturally, this statement provoked further public outcry. And with McCarthy banging the drum in Congress, the Senate felt compelled to conduct its own investigation. The Armed Services Committee formed a subcommittee chaired by Senator Raymond Baldwin of Connecticut, with Kefauver and Wyoming Sen. Lester Hunt rounding out the membership.

McCarthy was not named to the subcommittee, but was granted permission by Baldwin to attend the hearings as an observer. This would prove a deeply unwise decision.

The subcommittee interviewed over 100 witnesses and made a determined effort to figure out the facts. Their efforts, however, ran smack into a determined opponent: McCarthy, who did his level best to undermine the proceedings with the over-the-top histrionics that would become his trademark.

McCarthy ranted and raved about the “shameful episode” of the tribunal. He read into the record letters he’d received containing wild accusations about the behavior of the Dachau investigators. He badgered and aggressively cross-examined witnesses, and called his own. When Baldwin tried to shut him up, McCarthy loudly demanded to “complete my interrogation of this witness” (even though, again, he was not a member of the subcommittee). In the official transcript of the hearings, McCarthy’s name appeared almost 2,700 times – more than anyone except subcommittee chair Baldwin. (Hunt and Kefauver appeared fewer than 600 times and 200 times, respectively.)

McCarthy centered his accusations on the chief interrogator, Lt. William Perl, a Czech-born Jew whose wife escaped from a concentration. McCarthy repeatedly asked witnesses whether they had seen Perl kick or knee German defendants in the groin. When Perl himself took the stand, McCarthy accused him of lying and challenged him to take a lie detector test. Perl said he was willing to do so, but Baldwin shut the idea down.

This gave McCarthy the opening he sought to storm out of the room, accusing Baldwin and the subcommittee of attempting to “whitewash” the truth and dramatically announcing, “I feel that the investigation has degenerated to such a shameful farce that I can no longer take part therein” and requesting that Baldwin “relieve me of the duty to continue.” (That last bit is especially hilarious; McCarthy had no “duty” to the subcommittee since he wasn’t part of it.) Baldwin, no doubt relieved to be done with McCarthy and his shenanigans, said that he was sorry “the junior Senator from Wisconsin, Mr. McCarthy, has lost his temper and with it, the sound impartial judgment which should be exercised in this matter.”

Ever shameless, McCarthy promptly put out a press release blasting the subcommittee’s investigation, stating: “The subcommittee is not sincere in its investigation; it is not conscientious in pursuing the facts.” The Armed Services Committee – backed by leadership in both parties – responded by casting a unanimous vote of confidence in Baldwin and the subcommittee and condemning McCarthy’s “most unusual, unfair, and utterly undeserved comments.”

With McCarthy out of the way, the subcommittee resumed its work. In October 1949, they released a report of their findings. While they dinged the Dachau interrogators for some missteps – using mock trials to gain confessions and trying officers and subordinates together – they concluded that the accusations of abuse and torture were false. The prisoners had generally been treated well, and their trials were fundamentally just. Many of those who had claimed mistreatment recanted or gave conflicting testimony to the subcommittee.

As for Baldwin, he’d had more than enough of McCarthy – and the Senate. In December 1949, he resigned in the middle of his term to accept a judgeship back in Connecticut.

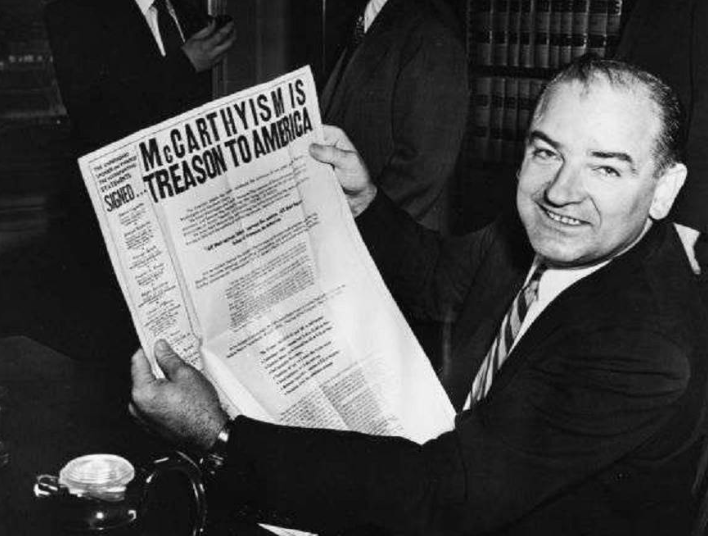

McCarthy, meanwhile, was just getting started. Honing the tactics of aggressive, ill-informed jerkitude that he’d pioneered during the Malmedy hearings, he proceeded to slash and burn his way through Washington with vaguely-sourced accusations of Communism and homosexuality in the executive branch and the Army until he was finally censured by the Senate in 1954.

After his downfall, McCarthy was repudiated by members of both parties. Senator William Jenner referred to him as “the kid who came to the party and peed in the lemonade.” And Jenner was his friend. McCarthy’s successor in the Senate, Democrat Blll Proxmire, called him a “disgrace to Wisconsin, to the Senate, and to America.”

If McCarthy’s Senate colleagues had paid more attention to the Malmedy hearings, they would have seen what was coming.

Leave a comment