If Estes Kefauver had a stock in trade as a politician, it was his handshake. To Kefauver, the handshake was a foundational pillar of political campaigning. When he was first campaigning for the Senate in 1948, Silliman Evans – publisher of the Nashville Tennessean – told him that the paper would support his candidacy as long as he promised to “shake 500 hands a day between now and election day.” Kefauver held true to his promise, and he used that number as a benchmark for all of his future campaigns.

But those 500 handshakes weren’t a meaningless metric to be pursued for its own sake. Kefauver believed that personal contact was critical to winning votes. When asked if he had any advice for aspiring candidates, Kefauver said: “Shake every voter’s hand you can shake – but you really have to mean it. Personal contact is priceless, but if you don’t really like people and your association with them, it will show through.”

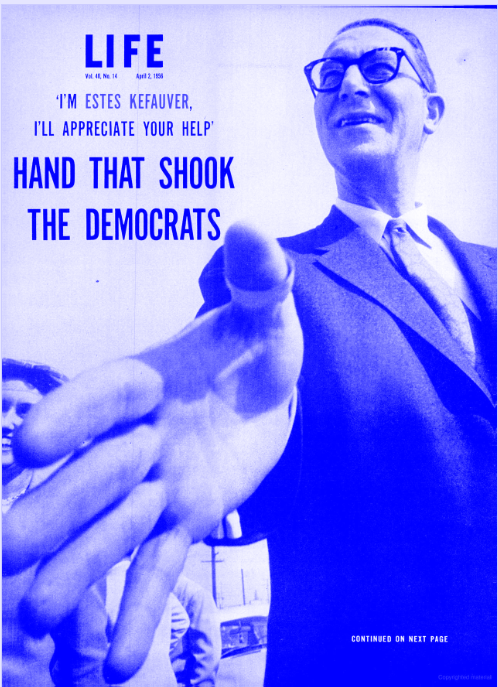

When he pursued the Presidency, Kefauver treated the primaries just as if he was running for the Senate back in Tennessee. Although he’d become a viable contender in 1952 thanks to the national fame he’d gained from his televised hearings on organized crime, Kefauver was not about to depend on his celebrity to get votes. He doggedly criss-crossed the country from one primary to another, shaking hundreds if not thousands of hands each day, repeating his humble appeal. “I’m Estes Kefauver. I’m running for President. I’d appreciate your help.”

In doing this, Kefauver set the standard for modern Presidential campaigning. In an age when state primaries were still a novelty, his brand of retail campaigning created an example that is still followed today. When candidates brag about visiting all 99 counties in Iowa, or popping into diners and VFW halls all over New Hampshire, they’re following in Kefauver’s footsteps.

Kefauver’s tireless campaigning bemused the press, many of whom saw it as another example that he was out of his depth as a Presidential candidate. Was he really going to become President by campaigning like he was running for Congress, or county sheriff? But in time, the reporters came to respect (if grudgingly) his personal campaigning style. Even Time magazine – no great fan of Kefauver – wrote with admiration:

The Kefauver handshake has deservedly become a national monument. It is not bone-crushing, or even firm. It is limp but not clammy. An inward turn of the wrist prevents pressure that would later cause aches and pains… Kefauver does not chatter as he shakes; he utters one friendly sentence and reaches for the next hand. As he shakes with his right hand, he applies a light pressure with his left on his well-wisher’s right elbow, thus keeping the line moving. When someone launches an extended conversation, Kefauver seems to give undivided attention—but he grabs for the next hand in line. The resulting traffic pile-up generally gets rid of the talker.

Indeed, Kefauver’s 1952 campaign was so effective that even Adlai Stevenson – the patrician intellectual who approached retail politics as cheerfully as a man facing a firing squad – realized he’d have to copy Kefauver’s style in the 1956 primaries if he wanted to win renomination.

And so they both flew around the country, shaking hands and greeting voters to the point of exhaustion. By campaign’s end, Time reported, Kefauver was so weary that he even attempted to shake hands with a cop that was writing his driver a speeding ticket.

Some of Kefauver’s friends said he never fully recovered from the exhaustion of that campaign – or his subsequent fight for reelection to the Senate in 1960 – and this contributed to his untimely death at age 60. But as far as Kefauver was concerned, there was no alternative. The only way to really connect with people – whether across the state or across the United States – was one hand at a time.

Leave a reply to On, Wisconsin: Kefauver’s Campaign Magic at Work – Estes Kefauver for President Cancel reply