Even in his time, Estes Kefauver was not generally known for his views on foreign policy. He never served on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee (though he eagerly sought a spot there while he still harbored Presidential ambitions), and his public reputation largely rested on his work with domestic issues like organized crime, civil liberties, and corporate monopolies.

He did have one major foreign policy idea, however: he was a steadfast supporter of Atlantic Union. Before doing my deep dive into Kefauver’s story, however, I’d never heard of the concept. Clearly, it had never come to fruition, or I would have been familiar with it. So what was Atlantic Union? Why did Kefauver spend so much time and energy on it? And why didn’t the concept ultimately pan out?

An Idea Born in the Shadow of WWII

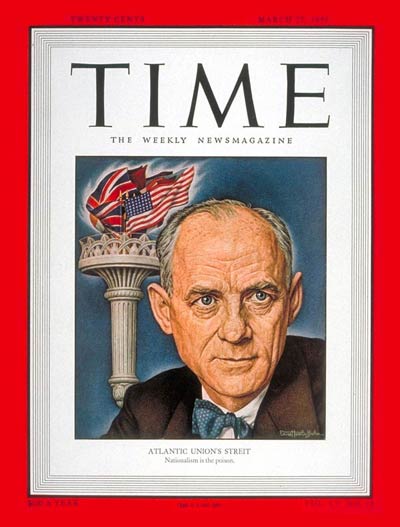

The father of the Atlantic Union concept was a journalist named Clarence Streit. As a corresponding covering the League of Nations for the New York Times in the late 1930s, Streit watched with horror at the rise of fascism and imperial aggression, and correctly foresaw both that it would lead to world war and that the League of Nations was not strong enough to prevent that outcome.

Streit detailed his proposal in a book called Union Now, published in 1939. The book outlined his plan for a “Federal Union of the free” initially involving 15 countries including the democracies of Northern and Western Europe, the US, Canada, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand.

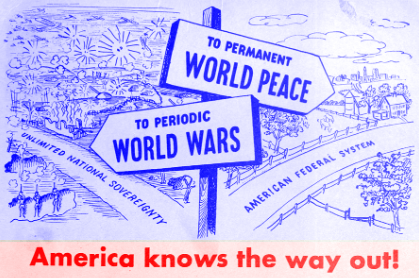

The union would be more than a military alliance, but a genuine political and economic federation with a central authority receiving some – but not total – power, modeled along the lines of the federal vs. state power split in America. Over time, Streit envisioned the federation agreeing to add members who were committed to democracy, with the long-term goal being a federation that spanned the globe.

Upon its release, Union Now had its detractors. Most notably, George Orwell savaged the concept in a famous essay whose title I won’t repeat here. Orwell allowed that Streit meant well, but claimed his vision would ultimately serve as a cover for continuing colonialism and further exploiting less-developed countries. “The British and French empires,” Orwell wrote, “with their six hundred million disenfranchised human beings, would simply be receiving fresh police forces; the huge strength of the USA would be behind the robbery of India and Africa.”

However, many others considered Streit’s idea worth pursuing. Even after the Axis powers were defeated in World War II, the rise of the Soviet Union and the Communist triumph in the Chinese Civil War led to a pervasive sense that World War III might be just around the corner, and the democratic countries of the world needed to do something to counter the looming threat of Communism.

Kefauver Joins the Cause… and Leads the Way

Kefauver was introduced to the concept of Atlantic Union in 1948, while traveling around Tennessee to gauge support for a potential Senate run. In Memphis he met with Lucius Burch and Edmund Orgill, who both strongly supported Atlantic Union. Burch gifted Kefauver a copy of Union Now.

Shortly after the meeting, Kefauver hurried back to Madisonville to be with his dying mother. He read the book while sitting at her bedside, and he found the idea compelling.

Upon his return to Congress after his mother’s passing, Kefauver inserted a pro-Atlantic Union speech by Orgill into the Congressional Record, noting that “to sustain a lasting peace, steps other than the European Recovery Plan [aka the Marshall Plan] are going to be necessary.” He also made Atlantic Union a plank in the platform of his Senate campaign.

If Orgill and Burch were concerned that Kefauver had adopted the idea just to secure their backing for his campaign, the newly-elected Senator quickly showed otherwise. In 1949, he introduced his first resolution in favor of Atlantic Union, attracting 20 co-sponsors. The resolution failed, but Kefauver was far from done with the idea.

During a 1950 hearing, Kefauver grilled a pair of State Department staffers – one of whom was future Secretary of State Dean Rusk – over their lukewarm opinion on Atlantic Union.

Kefauver attacked the Cold War status quo, saying that “the people are getting awfully tied of the expense of a cold war when they don’t see any great something that we are seeking or trying to arrive at.” He called on the State Department to “take into consideration the attitude of our people in wanting some great exploration, some star to hitch our wagon to, and also the attitude of people in other parts of the world.”

When Rusk cautioned that there was danger in committing too fully to the idea of Atlantic Union, Kefauver shot back: “[I]f the State Department is afraid in the conduct of its foreign policy to explore along the lines that saved this nation and made us the strongest union, well, then, I am afraid we are being very week in our efforts, Mr. Rusk.”

The following year, Kefauver introduced another Senate resolution calling for exploration of the idea. Although he landed 27 co-sponsors this time around, the bill failed again.

Changing Tactics: Building a More Perfect NATO

With Atlantic Union going nowhere in Congress or the White House, Kefauver switched to a different strategy.

His new approach revolved around the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), which was started in 1949. Kefauver disliked the fact that NATO was envisioned solely as a military alliance, but voted nonetheless to ratify the alliance, calling it a “necessary interim measure” to allow time to pursue “a far more promising prospect – the possibility of eventually uniting the democracies of the North Atlantic by our own basic Federal principles into a great Atlantic union of the free.”

In his speech, Kefauver described the American Constitution as “a basic foreign policy to govern the relations of sovereign States with each other, and with all the rest of the world” and called on the world’s democratic countries to unite along similar lines in order to safeguard liberty.

“Twice in our lifetime we have tried to secure freedom without war,” Kefauver warned. “Twice we have failed. Twice the boys have had to save the day, make up for their elders’ lack of vision, wisdom, self-sacrifice, and courage.”

If NATO wasn’t quite what Kefauver wanted, he would try to shape it into what he did want.

In 1954, NATO published a Declaration of Atlantic Unity, which called on the NATO nations to explore expanding their alliance beyond military cooperation, stating that “[d]efense in today’s terms extends beyond military requirements into the political, economic and cultural aspects of our lives.” Kefauver enthusiastically endorsed the Declaration.

The following year, Kefauver tried yet another Senate resolution calling on the President to convene an Atlantic Exploratory Commission among NATO nations, but the State Department’s continued opposition killed the idea. Instead, Kefauver went about establishing the NATO Parliamentarians’ Conference, a gathering of legislators from member countries with a goal of exploring the possibility of Atlantic Union. The first Parliamentary Conference occurred in Paris in July 1955, and continued on an annual basis thereafter.

As chair of the Parliamentarians’ Conference’s Political Committee, Kefauver convinced the group to unanimously support an Atlantic Congress, which was held in London in June 1959. The Congress included over 600 delegates from all 14 NATO member nations, including a 130-member American delegation that included 16 members of Congress. Queen Elizabeth II, in the opening speech of the Congress, expressed her hope that the gathering would bring “the peoples of the Atlantic Community… one step closer to a practical system of cooperation.”

Kefauver addressed the final plenary session of the Atlantic Congress with a soaring speech that cited the Sermon on the Mount, the French Declaration of Rights, and the US Constitution. He called on the NATO members “to work for a more perfect community of nations” and stated, “It is my hope – and indeed my prayer – that the concepts of political and economic unity that have emerged from this Congress will be enduring.” He concluded by calling on the delegates to “attempt to bring about implementation of our decisions in our own national bodies.”

The following year, Kefauver introduced one more Senate resolution calling on the President to appoint a committee of citizens to attend an Atlantic Union meeting on behalf of the government. The Foreign Relations Committee modified the resolution to state that the delegates would not be speaking for the government. With the backing of the Committee and Vice President Nixon, Kefauver’s long-sought resolution finally passed. The dream of Atlantic Union seemed closer than ever.

In January 1962, the American delegation created through Kefauver’s resolution attended the Atlantic Convention in Paris, which adopted a set of proposals that would put NATO on the path to becoming an Atlantic federation within a decade. The proposal included a High Council which would rule on “matters of common interest,” as well as an Atlantic High Court of Justice to resolve disputes between nations and a trade partnership between Europe and North America. The Parliamentarians’ Committee would be converted into an Atlantic Assembly, which would review and make recommendations to the other institutions.

At the Parliamentarians’ Conference that November, Kefauver presented the Second Declaration of Atlantic Unity. The Second Declaration stated “[t]hat sovereignty of the individual and freedom under law are mankind’s most precious political heritage” and “[t]hat only by our unity can we preserve the liberties we enjoy and only by our example will they appeal to all mankind,” and called on the NATO nations to adopt the proposals of the Atlantic Convention.

Though there was a long road ahead to turn that vision into reality, momentum for Atlantic Union was steadily building.

Streit certainly felt that way, and he credited Kefauver for it. “When Estes entered the Senate there was no talk I heard there of even such things as ’the Atlantic community,’” said Streit. “It is a measure of his courage, vision, and steadfastness that such talk is now commonplace.”

Kefauver’s Death Spells Doom for Atlantic Union

The following summer, though, Estes Kefauver died. The prospects of Atlantic Union seemed to die with him.

The proponents of the idea continued their efforts after Kefauver’s death. In 1966, Edward Meeman – former editor of the Memphis Press-Scimitar and longtime Kefauver ally– created an endowment to establish the Estes Kefauver Memorial Foundation, which would grant awards to people working “to bring about a union of the freed peoples of the world.”

Vice President Hubert Humphrey announced the endowment with a lovely tribute to Kefauver’s life and work. His prepared remarks announcing the “Union of the Free Award” proclaimed, “Someday there will be such a union.” But Humphrey crossed those words out and never delivered them. His deletion proved prophetic.

Our foreign policy attention was shifting. Instead of trying to combat Communism through union with Europe, America started fighting it with guns and bombs in Southeast Asia. Without Kefauver’s tireless support, the US lost the will to pursue Atlantic Union. And without US involvement, Atlantic Union was a non-starter.

A Lesson for Today?

The concept of Atlantic Union feels strange today, as much a Cold War relic as the Red Scare. Anything that reeks of “one-world government” is inherently suspicious to many modern Americans. If anything, we seem to be moving away from the concept of transnational alliances. Just ask the UK in the wake of Brexit. Even though NATO has picked up some members recently, its future may be in question.

Even if Atlantic Union remains a pipe dream, however, I think there’s something worthwhile in the concept. The concept of a mutual alliance founded in individual sovereignty, democracy, and freedom under law seems like a welcome counterpoint to the blood-and-soil nationalism on the rise in many parts of the world today.

Kefauver biographer Harvey Swados may have summed it up best:

Many years ago [Kefauver] realized that rivers, mountains, and oceans, color of the skin and religion were unnatural boundaries for governments… In a world shrunken by fast transportation and faster communications and where men know how to destroy centuries of civilization in minutes, some stronger cement was needed to bind men together. To Estes Kefauver that binding cement was a belief in the dignity of every human being. On that foundation, he would have built a broader more enduring government than this planet has ever seen.

Pie in the sky? Maybe so. But it seems like a more inspiring vision for relations between nations than most of what’s on offer today.

Leave a reply to Frank Church and Estes Kefauver: Lone Wolves, Honest Men – Estes Kefauver for President Cancel reply