(featured image source: Bettmann archive)

Throughout his political career, Estes Kefauver was considered a friend of organized labor. Both local and national unions backed Kefauver at virtually every turn along the way. It was rare, then as now, to find a Southern politician who was pro-labor, and the unions knew it.

But how did Kefauver become a pro-labor politician? He had no particular connection to the movement growing up; his family tree was full of doctors and lawyers, and during his time as a lawyer before his political career, Kefauver’s firm specialized in corporate law. What caused him to become so friendly to the unions? The answer lies in one of the things that made Kefauver such a rare politician – his willingness to listen.

In 1934, labor unions were beginning efforts to organize the textile mills in Chattanooga. Unsurprisingly, this proved upsetting to the local business community, many of whom were friends with Kefauver, than an up-and-coming lawyer. During a Constitution Day speech before the Sons of the American Revolution, calling the unions “a small radical group [that] has taken the law into its own hands” and encouraging the governor to call up the militia to break strikes.

The labor movement reacted with outrage. The Central Labor Union adopted a resolution condemning Kefauver for “drap[ing] the American flag about his shoulders and pictur[ing] the strikers as law breakers.” The union’s newspaper, Labor World, ran an editorial calling him “Estes Kickover” and slamming his anti-labor position.

Kefauver responded by showing up at the Labor World offices and telling the editor that he’d read the editorial. The editor braced himself, expecting a tirade. Instead, he was shocked as Kefauver said, “I guess you’re right. I don’t know too much about the subject.” Kefauver continued, “I thought it might do me good to meet some of you fellows in the labor movement and find out what the facts are.”

Once the editor picked his jaw up off the floor, he arranged meetings between Kefauver and local labor leaders. True to his word, Kefauver listened and changed his views. When he began backing labor’s position in local political matters, the union realized that he really had taken them seriously.

Once he was elected to Congress, Kefauver didn’t vote with labor on every issue – as he said, he studied each bill on its merits – but he was on labor’s side in the big fights. In 1946, he opposed the Labor Disputes Bill, which would have dramatically curtailed unions’ ability to strike, and voted to sustain President Truman’s veto. He was one of only two Tennessee Congressmen to oppose the bill. Later that year, he voted against excluding agricultural laborers from the protections of the National Labor Relations Board.

The biggest labor-related fight during his House career concerned the Taft-Hartley Act, a major attempt to crack down on union activity. Kefauver found many of the Act’s provisions objectionable. He opposed the ban on closed-shop contracts (that is, contracts requiring employers to hire only union members). He didn’t like the requirement that labor unions make their financial books public, noting that the same thing wasn’t required of corporations. And he objected to the provision allowing unions to be sued for breach of contract.

Kefauver opposed the bill in every vote on it, even though it was supported even by a majority of his fellow Democrats. Ultimately, the Act was enacted even over Truman’s veto, but the unions never forgot his steadfast support throughout the fight. (Kefauver continued to criticize Taft-Hartley even after its passage. During his 1952 Presidential campaign, he called the Act “a labor-management law that is one-sided” and claimed the Act “was design to push unions around.”)

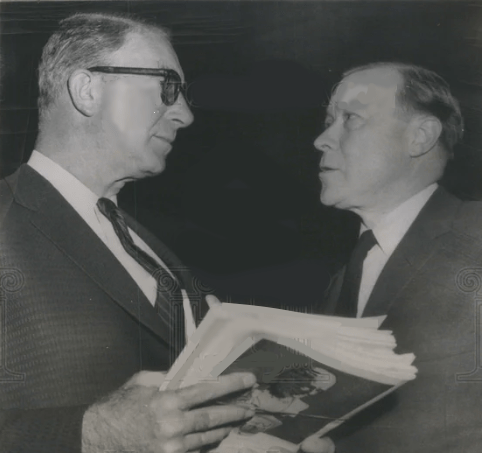

As a Senator and as a Presidential candidate, Kefauver retained union support. He was friendly with Walter Reuther, president of the United Auto Workers and the Congress of Industrial Organizations (which eventually became part of the AFL-CIO). Reuther strongly supported Kefauver’s bid for the vice presidency in 1956. A few years later, at Reuther’s urging, Kefauver included the auto industry in his hearings on monopoly.

As the AFL-CIO became more directly active in politics in the late ’50s and early ’60s, Kefauver was one of the prime beneficiaries. During his final campaign in 1960, Kefauver received more support from the AFL-CIO than any other Senator. Union members made over 60,000 calls, distributed over 160,000 leaflets, and mailed over 300,000 pieces of campaign literature on his behalf.

No doubt the unions were pleased by the way Kefauver’s monopoly hearings exposed corporate attempts to blame labor costs for rising prices. In the case of the auto industry, Kefauver’s hearings showed that labor costs accounted for only 15 to 20 percent of the price of cars – and that yearly restyling, ever-larger engines, and corporate profits were actually behind higher prices. Meanwhile, the steel industry regularly cited labor costs as the reason it had raised prices a dozen times since the end of World War II. Kefauver’s hearings showed that the industry’s preferred metric of “cost per employee-hour” was skewed, since technological progress was steadily improving employee productivity.

In reality, both the steel and auto companies were setting their prices based on what they felt the market could bear, and were making little or no effort to compete on price. Labor was simply a convenient scapegoat.

(Naturally, Kefauver being Kefauver, he wasn’t afraid to hold his friends to account. At the time of his time, he was reportedly planning hearings into anti-competitive practices by organized labor. No one could fairly accuse him of being a union stooge.)

In modern times, politicians on both sides of the aisle are infamous for treating even honest, well-intended criticism as a personal affront, Their social-media armies are poised to take up arms at any negative mention. If only more of today’s leaders would follow Kefauver’s example, and consider the fact that they might be able to learn from their critics. As his history with organized labor shows, you never know what you might learn if you’re willing to listen.

Leave a reply to Advise and Dissent: The Short, Controversial Life of the DAC – Estes Kefauver for President Cancel reply