(featured image source: Time Magazine archive)

After coming up short in his second bid for the Presidency, Estes Kefauver arrived at the 1956 Democratic convention unsure of what his future held, and wary of another slap in the face from the party establishment. He walked away at the convention’s end with the Vice Presidential nomination, and one more shot at a national campaign. As it turned out, that turned out to be both a blessing and a curse.

Surprise – and Victory – in Chicago

Kefauver arrived in the Windy City with one goal: capturing the VP nomination. His campaign opened a “Kefauver for Vice President” headquarters in a parlor at the Conrad Hilton Hotel. Unfortunately, since the campaign was (as always) broke, the only “hospitality” they could afford was three barrels of beer.

Kefauver was hardly the only one there seeking the VP nod. He wasn’t even the only Tennessean vying for the spot. The state’s ambitious young governor, Frank Clement – a Kefauver rival – was thirsty for it. Since he controlled the makeup of the Tennessee delegation, he filled it with delegate who were loyal to him, not Kefauver. Clement also arranged to give the keynote address, giving him a golden opportunity to impress the delegates, much as Stevenson had done four years before.

Averell Harriman arrived still hopeful of swiping the Presidential nomination away from Stevenson. He still had Truman in his corner – the ex-President endorsed him publicly on the eve of the convention – and he knew from ’52 that the primaries alone didn’t determine the nominee. But with Kefauver working diligently to swing his delegates to Stevenson, Harriman never stood a chance. The Illinois governor rolled to victory on the first ballot.

That left open the key question: who would he choose as his running mate? Stevenson and his team were genuinely torn over the decision. In the end, he made a shocking call: he decided not to decide. Instead, Stevenson threw it open to the convention to choose the VP nominee. (This had the added advantage of providing some made-for-TV drama to a convention that had sorely lacked it.)

Kefauver’s instinctive reaction to Stevenson’s announcement was to pack up and go home. Given his experience in ’52 and party leaders’ continued coolness to him during his ’56 run, Kefauver felt – understandably – that the whole thing was a ruse to screw him over yet again. Campaign strategist J. Howard McGrath felt the same, telling Kefauver that “they’re using you for a sucker… don’t let them do it.”

But pollster Elmo Roper caught Kefauver just as he was packing to leave, and convinced him to speak to Stevenson first. Stevenson convinced him that the offer was sincere, and Kefauver decided to stay and fight for the nomination.

He had several advantages in his corner. In addition to the hundreds of delegates he’d amassed during the primaries, he had the backing of prominent labor leader Walter Reuther. However, he faced several serious opponents, including not one but two other contenders from his home state. In addition to Governor Clement (whose keynote speech was a bomb but was still trying), Kefauver’s Senate colleague Albert Gore, Sr. was trying for the nomination. So was Hubert Humphrey – despite the fact that he’d failed to deliver his own state for Stevenson – along with New York Mayor Robert Wagner and a young Massachusetts Senator named John F. Kennedy.

Kefauver entered the balloting as the favorite, but no sure thing. And once the first round was over, it was clear that it would be a two-man race: Kefauver vs. Kennedy. On the second ballot, with the help of the ever-wily Lyndon Johnson, Kennedy got New York and Texas in his corner to surge into the lead. As he continued to roll up Southern support, Kennedy got within 39 votes of the nomination.

Kefauver felt his chances slipping away, and he rushed off to find Humphrey. The Minnesota senator – who’d finished fifth on the first ballot – was crying over his dashed dreams. Kefauver hugged him and they cried together. Humphrey declared, “I’m for Kefauver!” and rushed off to the convention floor to work his supporters.

That left Tennessee, which was still – at Clement’s instruction – stubbornly holding out for Gore. At this point Silliman Evans, Jr., publisher of the Nashville Tennessean and a longtime Kefauver fan, had had enough. He reportedly grabbed Gore by the lapels and screamed, “You [SOB], my father helped make you and I can help break you! If you don’t get out of this race, you’ll never get the Tennessean’s support for anything again, not even dogcatcher!” Gore, seeing his life (at least his political life) flash before his eyes, agreed to withdraw.

That left just one more obstacle: old Sam Rayburn. The Texan was convention chair once again, and he felt no warmer toward Kefauver than he had in ’52, when he used every parliamentary trick in the book to screw the young upstart. And yet, with Kennedy on the brink of victory, Rayburn recognized Tennessee, where Gore withdrew in favor of Kefauver. He then recognized Oklahoma, Minnesota, and Missouri, who switched their votes to Kefauver, putting him back ahead of Kennedy. After some back-and-forth skirmishes, the Tennessean came out on top. (Kennedy ultimately withdrew and moved to nominate Kefauver by acclamation.) See for yourself here:

It’s never been clear why Rayburn allowed the convention to swing to Kefauver. Had the veteran speaker, 74 at the time, lost his fastball? Some theorized that Rayburn was duped by his lieutenant John McCormack, who was bitter over losing control of the party in Massachusetts to Kennedy and perhaps took the opportunity to exact revenge. Or maybe Kennedy’s support had simply topped out, and there was nothing Rayburn could do.

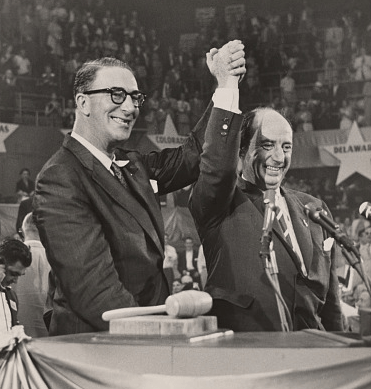

At any rate, Kefauver had finally triumphed. With the strains of “Tennessee Waltz” swelling through the amphitheater, he slowly worked his way through the crowd. Finally, sweaty and exhausted, he stood at the rostrum, grinning and waving. “I don’t know how you feel,” he began his remarks, “but I feel tired.”

There was little rest for the weary, though. The newly crowned Stevenson-Kefauver ticket had to get back on the road, waging their long-shot battle against the ever-popular Ike.

Making Friends in Flyover Country

If there was any concern among Democrats that Stevenson and Kefauver would let any of the bitterness of the harsh primary campaign come between them, those worries were quickly dispelled. “One thing about Democratic rivals,” said Kefauver as a campaign dinner, “they can kiss and make up.” (Stevenson quipped in response, “I’ll make up, but I’m damned if I’ll kiss you.”)

In early September, the running mates toured the country, holding a series of regional meetings to greet party leaders and stir up excitement for the fall campaign. Stevenson proclaimed the tour a success, saying, “Kefauver and I have traveled this country more and know it better than any other candidates in American history, as far as I know.” The lone hitch was that they were perpetually behind schedule because campaign staffers often had to tear Kefauver away from shaking hands, a task one campaign aide called “like pulling a fly off of flypaper.” (They did not have this problem with Stevenson.)

After the formal campaign kickoff on September 13, Kefauver set off on a barnstorming tour that would take him across 54,000 miles to over 200 cities and towns in 38 states, where he would make over 450 speeches and shake countless hands. Kefauver’s performance on the trail – and his connection with the voters – would lead one correspondent to call him “the single best asset Stevenson’s got.”

The campaign wisely focused Kefauver’s attention on the middle of the country. Biographer Joseph Gorman noted that Kefauver “was allowed to concentrate on what he was known to do best – symbolizing the Democratic party’s interest in the common man and carrying the Democratic message to his natural constituents in the Midwest… and West.” In these areas, he campaigned with what Time magazine described as “a soft pitch of hope, faith, and parity.”

Kefauver’s pitch went over well with his audience. A Kansas wheat farmer who met Kefauver in a restaurant said, “I thought he had something about him—that his words carried tremendous importance.” A Minnesota cattle rancher said, “Stevenson doesn’t come down to where the farmers are. Kefauver does.”

Missouri Rep. William Hull, Jr. summarized Kefauver’s appeal this way: “I think that he is the type of fellow who, if he was out campaigning and came across a farmer pitching manure, would take off his coat, grab another pitchfork and start to work.”

Going on the Attack

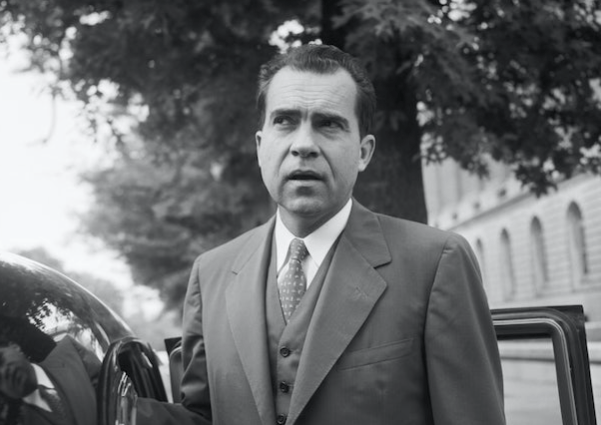

As is typically the case for vice-presidential candidates, Kefauver was called upon to play the attack-dog role. Although this was not his strong suit, he performed the duty faithfully. Wisely avoiding taking shots at the hugely popular Eisenhower, Kefauver instead trained his fire on Cabinet members – particularly Agriculture Secretary Ezra Taft Benson, whom he accused of “slid[ing] farmers deeper and deeper in debt” – and Vice President Richard Nixon.

Nixon was certainly an easy target for Democrats, given his reputation as a reactionary and a dirty campaigner. Responding to Republican attempts to present a more responsible and statesmanlike “new Nixon,” Kefauver drawled:

I want to say that I am delighted to hear about this new Nixon. I think we will all be glad to welcome him back to the company of civilized men, of men who believe that it is possible in this great democracy of ours to differ politically without assassinating each other and to campaign against each other without the necessity of impugning the motives, the patriotism, the decency and loyalty of our opponent or of the leaders of the other political party.

On October 17, Kefauver appeared on a national television and radio broadcast in which he walked voters through the “Republican Gallery of Broken Promises,” describing the alleged gap between Eisenhower’s campaign-trail promises and his actions in office.

Unfortunately, Kefauver made a couple notable gaffes. He accidentally claimed that Franklin Roosevelt, instead of Eisenhower, “has promised everything to everybody, but he has given everything to the privileged few.” Later, he claimed that Eisenhower had “stacked the National Labor Relations Board with pro-labor spokesmen”; he’d meant to say “pro-management spokesmen.”

Flattened by Ike’s Steamroller

Initially, it appeared that the Stevenson-Kefauver ticket was making some headway. In September, a Roper poll showed the incumbents holding a mere six-point lead. However, two overseas crises in October essentially doomed the Democrats’ chances and sealed Eisenhower’s re-election.

The first was the Hungarian uprising, in which university students led a revolt against the Soviet-aligned government (a revolt that was ultimately crushed under the treads of Soviet tanks a couple weeks later). The other was the Suez crisis, when the Israeli (backed by the British and French) attacked Egypt in retaliation for Egyptian president Gamel Abdel Nasser nationalizing the Suez Canal, a key international trade route.

The twin crises fueled the sentiment that it would be unwise to change leaders in a time of uncertainty, in addition to spotlighting Eisenhower’s foreign-policy credentials (and making the Democrats’ calls for a less hostile approach to the Soviet Union look foolish and dangerous).

In the end, the election was a blowout for the Republican ticket. Eisenhower won the popular vote by over 15 points and carried 41 states, including both Stevenson’s native Illinois and Kefauver’s native Tennessee. The Democrats were routed despite Kefauver’s tireless campaigning, up until the very end; in the campaign’s final week, he shook the hands of over 5,000 auto workers in Flint, Michigan. On Election Day, he actively campaigned in Miami, talking with everyone from aircraft mechanics to supermarket shoppers for over four hours. “It’s absolutely insane,” said one campaign aide of Kefauver’s manic schedule, “but he just can’t stop.” It wasn’t enough to change the outcome.

The Death of a Dream… and Make Way for JFK

The campaign took a tremendous toll on Kefauver. When he went to purchase some new suits after the campaign, he discovered that he’d lost two inches off his waist and a half-inch around the collar. He assured reporters that the weight loss was only temporary, noting that ”after a few meals of black-eyed peas and Tennessee country ham, I expect to pick up all the weight I’ve lost.”

Although he didn’t know it at the time – or at least wouldn’t admit it publicly – the 1956 campaign marked the end of Estes Kefauver’s quest for the Presidency. For a man whose desire for the office burned so brightly that it even baffled his wife, it must have been a tough blow to take. In the remaining years of his life, however, he would refocus his energies on his Senatorial career, where his greatest accomplishments lay ahead.

While the outcome of the campaign greatly disappointed Kefauver, it pleased another ambitious Democrat. For years afterward, John F. Kennedy would remark on how close the Vice-Presidential sweepstakes at the Chicago convention had been. But for a couple of breaks, Kennedy noted, “I might have won that race with Senator Kefauver – and my political career would now be over.”

Leave a reply to Advise and Dissent: The Short, Controversial Life of the DAC – Estes Kefauver for President Cancel reply