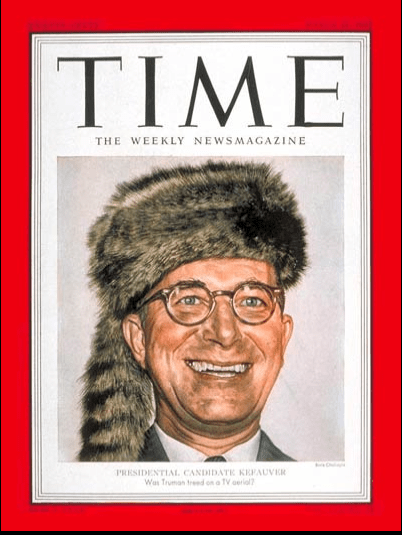

(featured image source: Time Magazine archive)

The first picture I ever saw of Estes Kefauver was the Time magazine cover shown above, which appeared right after Kefauver’s win in the New Hampshire primary in March 1952. I found the picture a bit… baffling. A grown man wearing a coonskin cap? I thought this was the 1950s, not the 1850s.

When I learned that the hat was Kefauver’s trademark (one newspaper dubbed him “the high priest of coonskin caps”), this only deepened my confusion. Sure, those caps were popular in the ‘50s… with preteen boys. Was Kefauver suddenly expecting the voting age to drop to 9? What was going on?

My original theory was that Kefauver adopted the coonskin cap as a nod to Davy Crockett. That made a certain amount of sense. I knew that there was a popular movie about Crockett that came out in the ‘50s. (Sing along, everybody: “Davy, Davy Crockett/King of the wild frontier…”) Like Kefauver, Crockett was “born on a mountaintop in Tennessee,” and he also served in Congress. Perhaps the cap was a clever way for Kefauver to tie his own legacy to that of a folk hero in his home state.

There’s only one problem with this theory: the timeline doesn’t fit.

It wasn’t until 1954 that Walt Disney, desperate for a program to pair with construction updates on Frontierland as part of his “Disneyland” TV series, plucked Crockett from obscurity and made him (as played by Fess Parker) into a TV star and the hero of young boys nationwide. (For more on that fascinating story, check out Slate’s excellent One Year podcast on the Crockett craze.) Before that, Crockett was a minor historical figure at best, even in his native state. By the time the show came out, Kefauver was already well into his political career, with his 1952 run and that Time cover already in the rearview mirror.

So what gives with the coonskin cap? The actual story is pretty fascinating in its own right.

The year was 1948, and Tennessee state politics were under the control of Memphis political boss E.H. Crump. (For those of you who thought political bosses only existed in Chicago and the big northeastern cities… think again.)

Crump-backed US Senator Tom Stewart (who first rose to fame as the chief prosecutor in the Scopes Monkey Trial) was finishing his second term. But for whatever reason, Crump soured on Stewart, and dumped him in favor of a circuit court judge named John Mitchell. An enraged Stewart ran for reelection anyway. Spotting an opportunity, Estes Kefauver – then a five-term Congressman and no fan of the Crump machine – also jumped into the primary, making it a three-way race.

Judge Mitchell turned out to be a dud on the stump, and the hard-campaigning Kefauver surged in the polls. Crump, facing a major blow to the power of his machine, blew a gasket. He took out giant ads in papers across the state attacking Kefauver as a Communist and likened him to a sneaky “pet coon that puts its foot in an open drawer in your room, but invariably turns its head while its foot is feeling around in your drawer.”

(You can see the ad for yourself here. It’s impressively unhinged.)

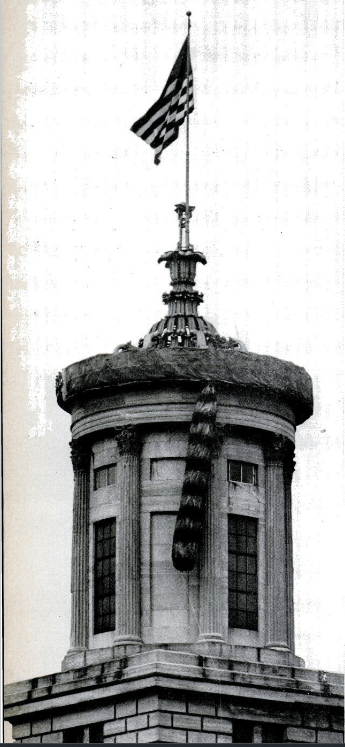

Kefauver’s response to the ad? At first, his campaign brought live raccoons to his campaign events, but this proved unwieldy. So instead showed up for his next campaign stop in Memphis (Crump’s backyard) wearing a coonskin cap. Thereafter, he adopted the campaign slogan, “I may be a pet coon, but I’m not Boss Crump’s pet coon!”

Kefauver went on to win the election, sparking the downfall of the Crump machine, and the cap remained his political symbol for years afterward.

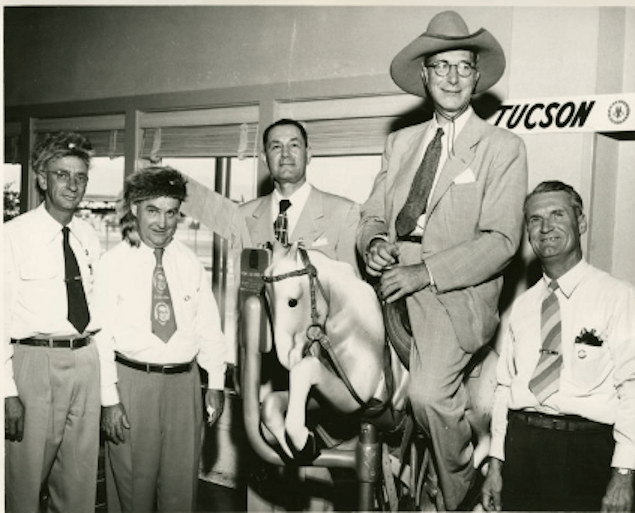

In retrospect, was Kefauver wise to choose the coonskin cap as his trademark? It’s hard to say. On one hand, it was certainly distinctive, and it brought a welcome splash of color to his fairly straitlaced personality. Plus, it allowed for great photo ops like this:

On the other hand, during the presidential campaigns, the cap made it easier for the Eastern sophisticates to dismiss Kefauver as a dimwitted rube from the sticks. Harvey Swados, in his Kefauver biography Standing Up for the People, agreed with this view, saying “unquestionably the coonskin cap damaged Kefauver nationally, particularly in the eyes of those who preferred to regard themselves as thoughtful, if not intellectual.” (The Time article associated with the cover at the top of this post was not especially kind.) And it’s worth noting that in his later campaigns, especially his 1956 Presidential ran and his Senate reelection bid in 1960, he opted for more typical headgear.

All that said, I’m glad that Kefauver adopted the coonskin cap. If he hadn’t, I might never have been intrigued enough to dive deeply into his remarkable story.

Leave a reply to Campaign 1948: Kefauver Beats the Machine and Enters the Senate – Estes Kefauver for President Cancel reply